Stephen Mullen

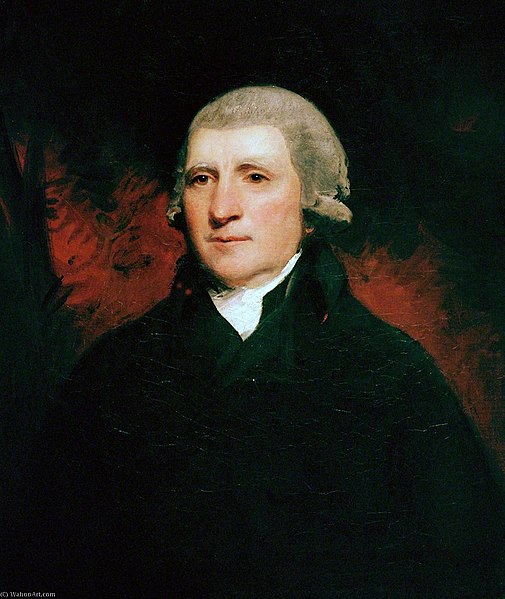

Since 2016 or thereabouts, there has been considerable public discussion about the role of Henry Dundas (1742–1811) in the debates surrounding the abolition of the slave trade in the House of Commons after 1792.

Dundas was the Lord Advocate in Scotland and went on to become one of the most influential politicians in the British Parliament. He was MP for Edinburgh and Midlothian, first lord of the admiralty, home secretary, and the first secretary of state for war. His political career was closely associated with that of his close ally, William Pitt the Younger.

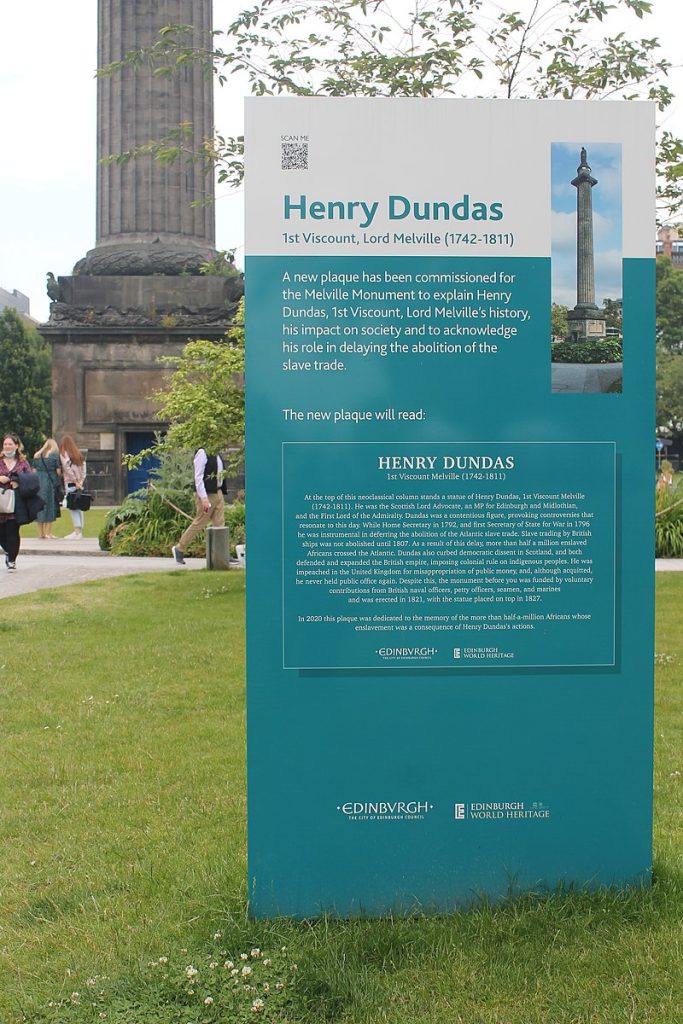

Dundas served in two Pitt ministries (1783–1801 and 1804–6), and acted as political manager, effectively controlling a personal party of Scottish MPs which ensured support for Government policies. A previous inscription on the Melville Monument provided details of this political career, yet did not mention Dundas’ controversial role in delaying the abolition of the slave trade, an era described as ‘gradual abolition’.

As home secretary (1791–4), he introduced the word ‘gradually’ to parliamentary abolitionist William Wilberforce’s motion of 2-3 April 1792 (which called for immediate abolition). This insertion provided scope for years of delay and outright blocking by pro-slavery interests in both the Houses of Commons and Lords. Dundas’s motives were grounded in imperial economics and security; he advocated an increase in the enslaved population to maintain the production in the British West Indies, which was the foundation of the British imperial economy.

With the onset of war with Revolutionary France in early 1793, the colonial security of the British West Indies became a pressing issue. As noted by Roger Buckley, from early 1795 both Henry Dundas and supposed abolitionist William Pitt promoted a government strategy of purchasing enslaved Africans for forced recruitment into West India regiments. Dundas’ parliamentary opposition to abolition during wartime was particularly evident in March 1796, when he spoke against immediate abolition in the House of Commons, whilst his phalanx of Scottish MPs voted to block abolitionist proposals.

There is no historiographical controversy about Henry Dundas’ culpability in delaying abolition. Roger Anstey (1975), David Brion Davis (1975), Roger Buckley (1975) and G.M. Ditchfield (1980) have all put forward compelling arguments about Dundas’ role in delaying abolition and associated political strategies. This remains the orthodox position amongst historians of slavery and abolition and has recently been endorsed by, for example, Seymour Drescher, Douglas Hamilton, Christer Petley and Katie Donington. However, some biographers have taken a more sympathetic approach. Although Michael Fry’s Dundas Despotism (1992) did not examine abolition debates in any detail (ending the analysis in April 1792) this work exonerated Dundas by claiming his insertion of ‘gradually’ made abolition more likely. Fry’s marginalisation of Dundas’ instrumental role in delaying abolition afterwards set the tone for Oxford Dictionary National Biography entries in 2004 and 2021. This is a revisionist position that did not actually revise the orthodoxy, yet Fry recently went further and claimed that Henry Dundas was a ‘genuine opponent of the slave trade’.

Edinburgh City Council announced new wording to the plaque on the Melville monument on 11 June 2020, which acknowledged Dundas’ role in delaying abolition. During the delay between 1792 and 1807 ‘more than half a million enslaved Africans crossed the Atlantic’ to which the plaque was dedicated.

Nevertheless, the debate over memorialisation went digital. In July 2020, leading Scottish journalist noted how Henry Dundas’ Wikipedia page was constantly amended to claim he was abolitionist. In March 2021, Leask also reported how ‘online anonymous Twitter accounts….engaged in detailed debates about obscure episodes of Dundas’s career’. My now published article ‘Henry Dundas: a “great delayer” of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade’, Scottish Historical Review (2021), therefore, adopted a distinctive approach; adding further evidence to historiographical orthodoxy yet also took note of a public defence that disregarded the works of several historians of slavery and abolition going back almost a half-century.

Read

About the author

Dr Stephen Mullen is a historian of slavery and its aftermath in the British Atlantic world, with a particular focus on Scotland and the Caribbean. He is an alumnus of the Universities of Strathclyde and Glasgow, completing a Ph.D. at the latter institution in 2015. Since then, he has been a Postdoctoral Researcher and Lecturer in History at the University of Glasgow. Stephen’s research has focused on the social and economic consequences of Atlantic slavery in a British-Atlantic framework. He was a Postdoctoral Researcher on the Leverhulme project ‘Runaway Slaves in Britain: bondage, freedom and race in the eighteenth century’, and the principal researcher and co-author of the report ‘Slavery, Abolition and the University of Glasgow’ (2018), which led to the sector-leading Reparative Justice strategy. A monograph, The Glasgow Sugar Aristocracy: Scotland and Caribbean Slavery, 1775-1838, is forthcoming with the Royal Historical Society/Institute of Historical Research flagship series New Historical Perspectives published by University of London Press.