By Brett Andrew Jones

It wasn’t every day that accusations of cannibalism flew around the early Jacobean court.

That’s (one reason) why I found the revised version of Mucedorus so interesting.

It hardly compares well to what we consider the heights of Shakespeare’s dramatic output but for contemporary audiences this play was a smash hit – reprinted more times than any other play of the period.

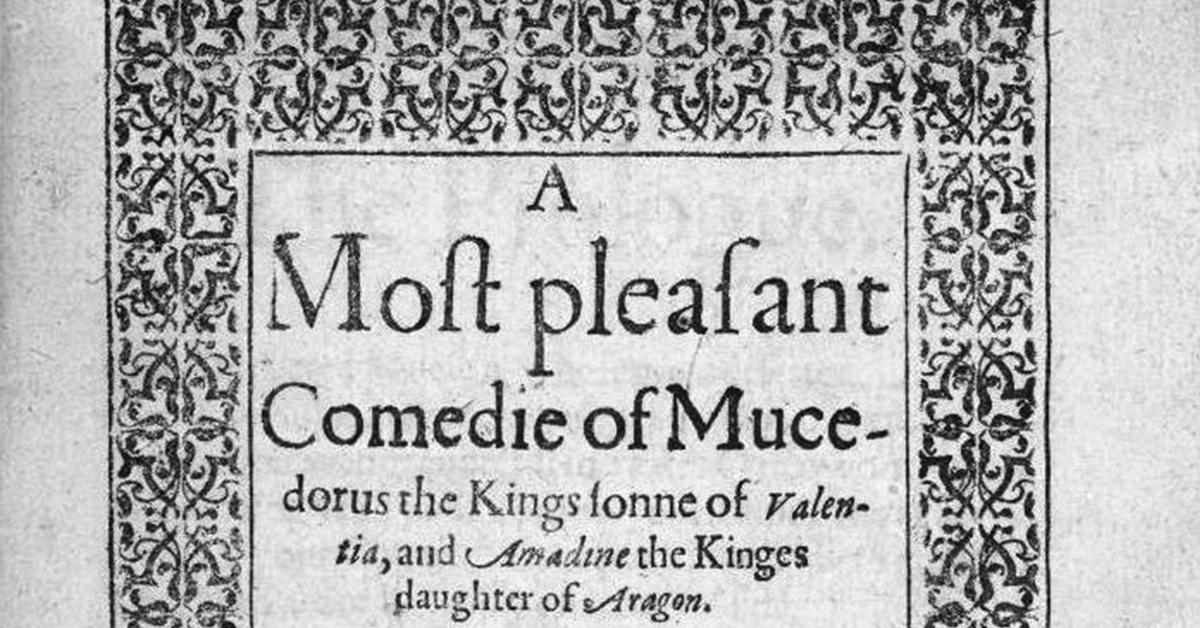

The third version was printed in 1610 as a result of a noteworthy staging. It’s cover states it was acted ‘Before the King’s Majesty at Whitehall on Shrove-Sunday night’. It came with some new lines included.

The plot is silly, but fun. The hero, Mucedorus, faces a myriad of challenges in his attempts to woo Princess Amadine. During his struggles the actors who play the allegorical figures of Comedy and Envy reappear in the midst of the action in other roles. The actor playing Comedy doubles as various comic characters but the actor playing Envy becomes much more malevolent figures. He transforms into Tremelio, a murderous army Captain and Bremio, a cannibalistic wild-man.

In the epilogue Comedy and Envy return. Comedy is victorious – the play and the romantic leads have enjoyed a happy ending. But Envy is not done yet. In the new lines, composed specially for this performance, he promises a new scheme to cause disruption.

His plan is a curious one. He will encourage a ‘cannibal’ and ‘him I’ll make a poet’.

Understandably, Comedy is unclear how this plan is meant to help Envy. ‘What is that to the purpose?’ he asks.

Envy is happy to elaborate. This cannibal poet he will ‘whet on to write a comedy; Wherein shall be composed dark sentences, Pleasing to factious brains’.

Only two months earlier another play, a comedy, had been performed before the court and it had indeed been accused of stirring up trouble.

T. S. Graves, in his essay Jonson’s ‘Epicoene’ and Lady Arabella Stuart, has shown how shortly before Mucedorus was put on for King James the extremely powerful Lady Arabella had been scandalized by a performance of Ben Jonson’s Epicoene.

She believed that a reference in the play to ‘the Prince of Moldavia and his mistress’ was directed at her. A few years previously the conman Stephano Janiculo had visited the court and, in the guise of the Prince of Moldavia, he had attempted to arrange a marriage with Lady Arabella.

King James needed to keep Lady Arabella happy – before his coronation as King of England she had been a possible candidate to succeed Queen Elizabeth. So Shakespeare’s company, as the King’s Men, needed to make amends. They referred to the trouble, insulted the playwright and reminded the court that this was an error committed by ‘boys, not men’. Jonson’s play had been performed by the boys of the Children of her Majesty’s Revels while the King’s Men were a company of adult actors.

The choice of ‘cannibal’ as the epithet to hurl at Jonson was very interesting to me. I discovered that this was a common way to insult Catholics at the time. If they believed in physical transubstantiation at the Eucharist then (so the logic ran) were they really any different from cannibals?

In Jonson’s conversations with William Drummond he says that he converted to Catholicism while in prison in 1598 and remained a papist for twelve years. This would put his abandonment of the Catholic faith sometime in the year 1610 – perhaps it was even linked to the Epicoene episode and the insulting lines penned about him as a result. But of course we can’t be sure of that.

It is sometimes suggested that Shakespeare himself wrote the 1610 additions to Mucedorus but it’s impossible to tell for certain. With so much at stake I do think it unlikely that the lines would have been included without at least consulting the company’s resident playwright. Shakespeare had vast experience in preparing his own plays for court performances (King Lear’s court performance in December 1606 had also been noted on the cover of its quarto).

My essay identifying Ben Jonson as the ‘cannibal’ poet of Mucedorus left me wondering how Shakespeare and Jonson interacted in the aftermath of the fracas. Rather than drive a wedge between Jonson and the King’s Men they began working together. Jonson’s next play, The Alchemist, was written for them and performed in Oxford alongside Othello in September 1610.

We do know what Shakespeare was writing later in 1610. In July William Strachey, freshly returned from a disastrous voyage to Bermuda, wrote his True Reportery which was a source for Shakespeare’s Tempest. That play features a character whose name is an anagram of ‘canibal’ (as the word is spelt in Jonson’s The Case is Altered printed in 1609) and in such a way as to make the end of his name sound a little like ‘Ben’.

Caliban even stresses the end of his name in song. ‘Ban, Ban, Cacaliban’ he sings to Stephano and Trinculo (whose names seem to suggest Stephano Janiculo). They ply him with wine (as Jonson claimed to have swigged a jug of communion wine to celebrate leaving Catholicism). And, as Jonson had left writing for the boy’s company to work with the King’s Men, so Caliban sings of himself and Prospero ‘[Caliban] Has a new master: [Prospero can] Get a new man’.

Read Brett Andrew Jones’ article, Identifying The Play Apologized for in the 1610 Epilogue to Mucedorus And Its “Cannibal” Poet in Ben Jonson Journal 28.1.

The Ben Jonson Journal is devoted to the study of Ben Jonson and the age and culture in which his manifold literary efforts thrived. Topics covered include poetry, theatre, criticism, religion, law, the court, the curriculum, medicine, commerce, the city, and family life, as well as the manifestation of these topics and other interests in Renaissance life and culture. Find out how to subscribe, or recommend to your library.