by Miriam Kent

Wanda Maximoff, known as the Scarlet Witch, is one of Marvel’s most enduring characters. Her history has spanned multiple decades and media formats. Disney+’s WandaVision recently receiving praise for its characterisation, aesthetics and settings. WandaVision inserted Scarlet Witch (Elizabeth Olsen) and her romantic and superheroic partner Vision (Paul Bettany) into a strange world apparently caused by Wanda’s witch-like reality-warping powers.

Given the character’s multimodal presence, we can think about Scarlet Witch in terms of adaptation and culture. Women in Marvel adaptations represent shifts in attitudes to women’s equality and feminism, as I discuss in my new book Women in Marvel Films. Many of these characters have what I call “textual baggage” that is negotiated when new versions of them are crafted.

By the time she appeared in WandaVision, Scarlet Witch was familiar to contemporary audiences, having appeared in Avengers films. However, she was created in 1964 by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby during the Silver Age of Comics—an era spanning the mid-1950s to 1970s. This era is associated with science fiction aesthetics and motifs, the reinvention of established superheroes and, for Marvel especially, stories with drama and soap opera-like character developments.

Wanda wasn’t always a hero, though, having been introduced in comics as a villain. This was reflected in Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015), in which she is depicted, alongside her twin brother Pietro, as a brainwashed recruit of the terrorist organization Hydra. As in the comics, Wanda eventually switches sides, becoming an Avenger.

Witches in Marvel Comics

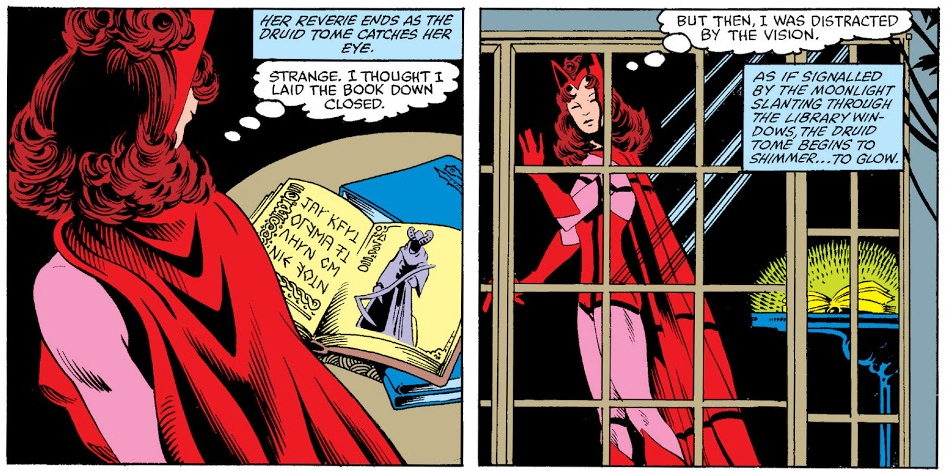

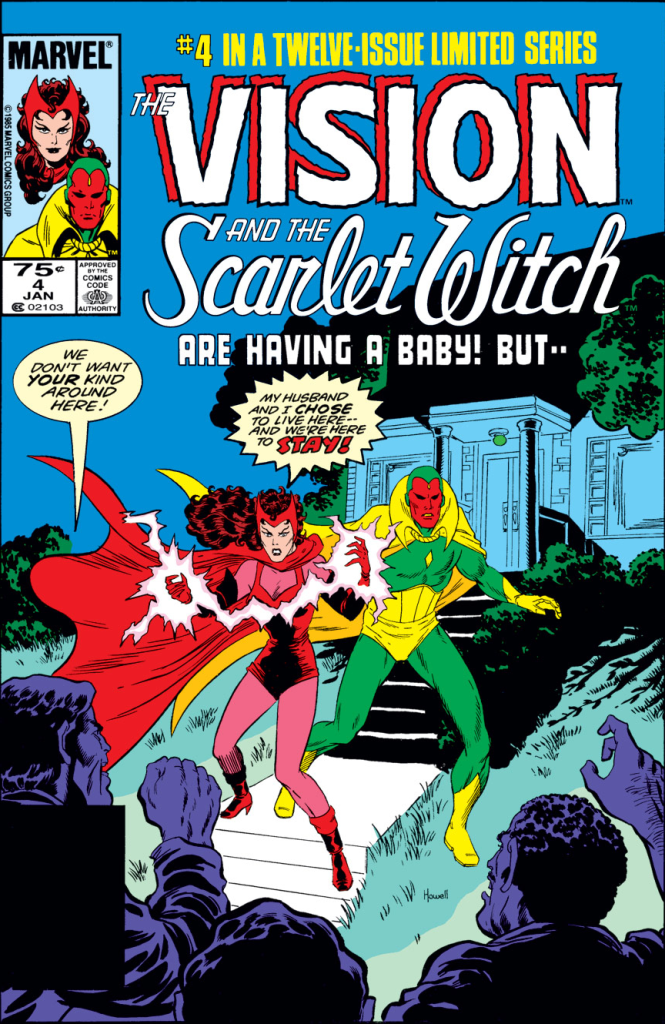

Wanda’s powers, once suggested to be limited to manipulating probability, eventually encompassed reality manipulation. This development stemmed largely from the 1980s comic series Vision and the Scarlet Witch (written by Mantlo & Englehart, pencilled by Leonardi & Howell), when her powers were increased, and their representation more obviously drew from the occult and magic. Here, she is shown under the tutelage of witch Agatha Harkness, who also makes an interesting appearance in WandaVision. Eventually, Wanda’s powers were extended to involve the manipulation of reality alongside a natural affinity towards witchcraft.

Witches have been a staple of Marvel media for some time. Intersecting with wider cultural ideas around abject femininity and the monstrous feminine (respectively discussed by Julia Kristeva and Barbara Creed), witches became a shorthand for female supervillains in Marvel texts. Even when not explicitly deemed witches, Marvel’s villainesses often draw from the iconographies of witches, such as when the X-Men’s Jean Grey becomes the evil Dark Phoenix. In the X-Men films especially, she is represented as mentally unstable, physically grotesque, flying, with long, dark hair, darkened eyes and billowing, cloak-like costuming. Her telekinetic powers are signified through overblown gesturing, causing destruction and even the death of her friends.

Like many superheroic women, Jean was portrayed as being unable to control her powers, culminating in a supervillainous hysteria specific to the notion of powerful women in the media. Like Jean Grey, Wanda was often represented as struggling to control her powers, especially in early comics. Similarly, Olsen’s gesturing and straining as she manipulates her surroundings signal Wanda’s powers in live-action representations. In many of these texts, the more power these women hold, the more dangerous they are suggested to be, indicating a wider discomfort with the idea of women wielding power. And the more power they hold, the more likely, it seems, they are to become evil.

From Monstrous Femininity to Hysterical Motherhood

In Age of Ultron, Wanda’s powers are described as “neural electric interfacing,” “telekinesis,” and “mental manipulation,” a realism-infused description of, essentially, witchcraft. The instability of her power is demonstrated in Captain America: Civil War, when she inadvertently causes the collapse of a building and the death of several civilians while on a mission.

The destruction caused by Wanda’s loss of control relates to interconnected stories in comics history. Wanda and Vision’s relationship resulted in the introduction of their twin babies—an odd development, considering Vision is an android and unable to reproduce. The comics dealt with this by making the twins a manifestation of Wanda’s magic. Through a complicated series of events, Wanda’s twins were ultimately removed from continuity, but her memory of them is triggered in 2004’s “Avengers Disassembled” storyline. On realising the extent of the loss of her children (who technically never existed because she conjured them up herself), Wanda loses her sanity, causing mass destruction and death. Her break with reality is so great that she creates a warped version of the world in which her twins are alive. A group of Avengers break her spell and continuity is restored—although Wanda wipes out most of the world’s population of superpowered mutants. Over the following years, the comics portrayed characters confronting Wanda’s actions, with some setting out to kill her in retribution.

While WandaVision’s representation of Wanda’s reality-warping is limited to one town, her actions are still informed by trauma after the death of Vision in Avengers: Infinity War. In triangulating mental instability, witchcraft and femininity, these narratives do little to break with media traditions. Wanda’s modification of the town of Westview involves the mind-control of the townspeople, who suffer internally at their lack of agency. While Wanda can move on from her trauma throughout the series (and the townspeople are freed), the ambiguous ending leaves room for speculation, especially around the loss of her children, who, as in the comics, materialised as a manifestation of her powers. As the voices of the twins haunt Wanda in the last scenes as she studies more ancient magic, one wonders how her representation will develop in future installments.

About the author

Miriam Kent has a PhD in Film Studies with a focus on Marvel superheroes from the University of East Anglia, where she has taught a wide range of Film, Media and Gender Studies courses. She has published on superhero media with an interest in gender, representation and adaptation. Her previous work has appeared in academic journals, including Feminist Media Studies. Women in Marvel Films is available now from Edinburgh University Press.

If you liked this post, check out our other articles in film studies and gender studies.