By Virginie Trachsler

Source: WikiMedia

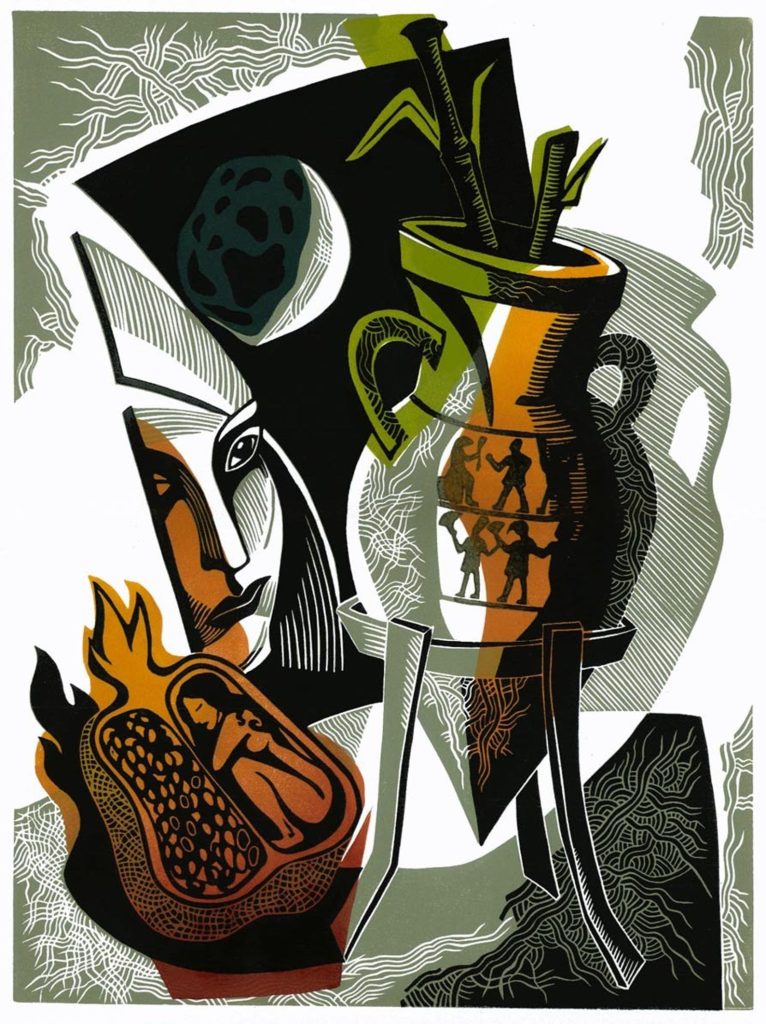

The young Persephone is gathering flowers in a meadow when her uncle Hades, god of the underworld, rises through a crack in the earth and abducts her on his golden chariot. Her mother Ceres wanders the earth for days trying to find her. In her despair she stops spring in its track: nothing will grow until she is given back her daughter. By the time Zeus intervenes, Hades has tricked Persephone into eating the seed of a pomegranate, binding her to the underworld forever. Eventually it is agreed that Ceres and her daughter will be reunited for part of the year, while she will spend the remaining time with Hades in hell.

In the Greek myth, Persephone is abducted in Sicily, but it is her presence on another island, Ireland, that I want to look at here. Many poets, women in particular, in Ireland and elsewhere, have turned to this myth to explore motherhood, mother-daughter relationships or the passage from girlhood into adulthood. The four poems I chose drag the myth into a contemporary setting while maintaining strong ties with the original story. The poets appropriate the myth and eventually emancipate themselves from it.

1. ‘The Pomegranate’, Eavan Boland

Eavan Boland frequently returned to the myth of Persephone and Ceres in her poetry. ‘The Pomegranate’ is her longest reinterpretation of this story. Boland identifies not with Persephone (though she notes that as a ‘child in exile’ in London, when she first encountered the myth, she did), but with her mother. Like Persephone in the underworld, the daughter in the poem ‘reached / out a hand and plucked a pomegranate’. The pomegranate merges with the forbidden Biblical fruit to become a symbol of the end of childhood innocence. The mother hesitates to warn her daughter and stop the myth from repeating itself, but decides against it in the very last line of the poem, ‘I will say nothing’.

While the bond between mother and daughter begins to change as the daughter grows older, it is also reinforced by their shared knowledge of the myth (‘the legend will be hers as well as mine’). Today’s Persephone will be Ceres tomorrow and she too will have to choose whether or not she lets the myth repeat itself once again.

2. ’Peirsefine’ / ‘Persephone Suffering from SAD’, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill and Medbh McGuckian

Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill writes in Irish. Northern Irish poet Medbh McGuckian translated this poem, simply entitled ‘Peirsefine’ in the original version, and as her addition to the title suggests, she makes the English poem more light-hearted and playful than its original.

In this poem, we switch perspective. The speaker is no longer the mother figure, but Persephone, who addresses her mother and tries to reassure her: she has just met a dashing Hades and

‘hitched a ride ‘gur thógas marcaíocht ón bhfear caol dorcha

with that sexy guy ina BhMW’

in his wow of a BMW’

The poet studs her text with subtle, tongue-in-cheek allusions to the myth, disguised as comments made in passing: ‘ach aon rud amháin, tá an tigh seo ana-dhorcha’; ’though I’d have to say there’s not much light in the place’. These remarks highlight Persephone’s ingenuity: Hades lures her with gifts and promises, and when she is offered a pomegranate (‘úll gráinneach’ in Irish), the reader knows that there is no going back. The poem closes on ominous ‘drops of blood’ (‘braonta fola’) dripping from the fruit: our modern-day, naive Persephone has just fallen into Hades’ age-old trap.

3. ‘The Light Thief’, Doireann Ní Ghríofa

The mother in Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s ‘The Light Thief’ does not heed the SAD-suffering Persephone’s advice: she goes to the police, who only ‘shrug at her abduction stories’. She is then left alone and grief-stricken to search for her addict daughter, as the mythical pomegranate morphs into ‘just these crystals, crushed, just this smoke, spinning up.’ ‘The last stop on the underground’ serves as a contemporary urban version of Hades’s underworld. Here, time proves to be Persephone’s ally in her escape, as it erases her name from the mother’s posters. ‘MISSING: PERSEPHONE’ first becomes ‘MISS____ PERSEPHONE’, and eventually fades to ‘___IS_______________’: nothing more than an affirmation of Persephone’s existence in the world, free to escape the contraints of her mythical name and the story attached to it. Still, it seems impossible to resist the pull of myth: Persephone goes back and forth between her lover’s ‘windowless basement squat’ and hospital rooms in which her mother tries to keep her. At the end of the poem, she goes ‘back home’, home to Hades, while her mother resumes her desperate search.

4. ‘Hades’, Róisín Kelly

In ‘Hades’ by Róisín Kelly, the god of the underworld becomes the title character. The mother figure is completely absent: it is the speaker as an older adult who looks back at her relationship and frames it in these mythical terms, addressing Hades. He takes centre stage, a position in the poem that mirrors his controlling attitude in his relationship to the female character:

You expected my

worshipful gaze

as you fed to me seeds

from the pomegranate

The worship ritual and the poem both end with a gesture of complete submission: ‘[you] asked me / to kneel before you’. But Persephone manages to resist the power of the pomegranate. As Róisín Kelly writes in another poem, she is ‘Persephone no more’: she has emerged from the underworld as an angered Jezebel, refusing the injunction to respect ‘the natural order of things’: ‘I am winter and summer / and spring’. Persephone, as a passive, naive figure, whose existence is governed by her mother or Hades, is left behind. This time, the cycle of repetition is definitely broken.

But Persephone, who comes and goes between worlds each year, is well used to making return trips. She comes back in Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s latest collection To Star the Dark. The myth finds renewed personal resonance in one of her ‘Seven Postcards from a Hospital’ where her infant daughter in Intensive Care is a Persephone in the underworld: ‘When I descend to the basement, I find her in an incubator, sleeping on her belly, my Persephone.’ The poet has crossed to the other side, and become Ceres.

Read Virginie Trachsler’s article, ‘‘The Need for Translation’: The Role of Translation in Eavan Boland’s Work‘ in Volume 30, Issue 1 of Translation and Literature.

Translation and Literature publishes critical studies and reviews primarily on English literary writing, of all periods. Its scope takes in the reception of ancient Greek and Latin works, the historical and contemporary translation of literary works from modern languages, and the far-reaching effects which the practice of translation has, over time, exerted on literature written in English. It embraces imitation and adaptation, including adaptation into other art forms; the theory of literary translation; and publishing history. It also publishes significant historical translations edited from manuscript sources.

A cumulative index of all articles from Volume 1 to the present is available here.

Find out how to subscribe to the journal, or recommend to your library.