‘How do you do it? I am dazzled’, enthused Evelyn Waugh in a letter to Muriel Spark in 1960. Spark’s latest novel, The Bachelors, was hot off the press, and this, Waugh told her, was ‘the cleverest and most elegant of all your clever and elegant books’.

If you’ve read anything by Spark, or much of the commentary that surrounds her life and work, you shouldn’t find Waugh’s praise all that surprising. Even before opening one of her typically slimline novels, we’re greeted by words like ‘dazzling’ and ‘elegant’ on the dust-jacket. We’re reminded by critics of her expert control of plot, whip-smart way with dialogue, and chilly, unsentimental treatment of death, violence and betrayal (Ali Smith coined a term for this latter quality: ‘Sparkian ice’). These are works, observed John Updike, which ‘linger in the mind as brilliant shards, decisive as smashed glass’. The message is clear: Spark’s books are to be admired from afar rather than intimately understood, as though each ought to come prefaced with the message, ‘look, but keep your distance’.

Spark’s Crystals

Ice, glass, elegance, dazzlement. We might add another entry to the lexicon of Spark-praise: ‘crystalline’. Spark’s novels, we’re told, exist as perfect crystals, each one a work of sparkling precision. Think of the carefully delineated temporal scope of her most famous work, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. Its narrator leaps habitually both backwards and forwards in time, totally assured of the implication each present action will have on the known future. Think, too, of Spark’s stiletto-sharp focus on specific, enclosed communities; as well as the members of Brodie’s classroom, we have Memento Mori’s feuding septuagenarians, Robinson’s desert island castaways, and The Girls of Slender Means’ boarding-house lodgers. In Sparkworld, we’re given the full cast of characters up-front and are often in little doubt about how much time stretches before them. Everything is crystal-clear, or so it appears.

‘Crystalline’ was Iris Murdoch’s term for a novel that presents itself as a ‘small quasi-allegorical object portraying the human condition and not containing “characters” in the 19th-century sense’. Spark seems to wear it well (even her surname captures something of the finite, intense thrill of her taut, economical prose and plots). And it’s this brusque, detached, ‘quasi-allegorical’ approach to plot and character that aligns the author with some of her most famous creations, including the megalomaniacal schoolteacher, Jean Brodie. Brodie stands poised and preened before her class, her words and actions exerting a powerful (and not always benevolent) influence over their present lives and future selves. Might we think of Brodie as Spark’s authorial surrogate, treating her pupils as Spark treats her characters?

Master of Puppets

It’s not uncommon, when reading critical commentaries on Spark, to find her characters described as puppets, dolls and dummies, and Spark as their merciless master-puppeteer. Spark’s Catholicism offers added value here: if her ‘crystalline’ works are allegorical in the way Murdoch describes, then perhaps their tendency to contrast present and future, alongside their refusal to dwell in depth on emotion and motivation, says something of the contrast between divine omniscience and human fallibility, and the relative insignificance of human lives when seen from a ‘God’s-eye’ view. We may be dazzled by Spark’s crystalline novels, but we feel the sharpness of their edges, too.

But is this the only way of reading Spark? Are her ‘crystalline’ fictions concerned purely with didactic displays of omniscience, or do they have something else to say? When I began researching Spark, I was struck by the dissonance between her critical reception and the numerous gaps, contradictions and inconsistencies in her narratives. Why is it that the narrator of The Driver’s Seat knows precisely what the future has in store for the protagonist, but can’t be sure of her age or hair colour? And what about Spark’s debut novel, The Comforters, whose supposedly all-powerful narrator is overthrown by a rebellious character? And doesn’t the flattened, affectless nature of the actors, publicists and agents in The Public Image (a novel about celebrity and scandal) say more about our contemporary, media-saturated culture than God’s view of human antics?

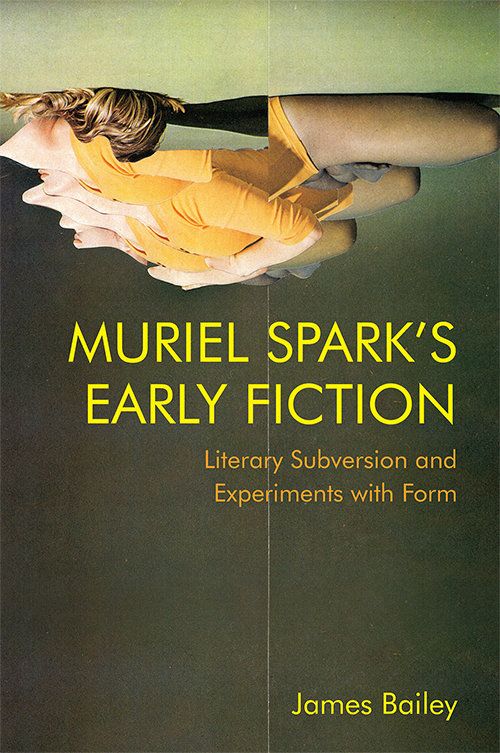

These were the questions that nagged at me as I wrote Muriel Spark’s Early Fiction. My book argues that, once you spot the deliberate flaws in Spark’s literary crystals, a diverse range of new readings can be explored. This is a book about Spark at her most strange and subversive, and one which claims – by focusing on instances of narrative daring during the first two decades of her literary career – that her work combines formal innovation with an ethically driven and often feminist method of storytelling. Spark emerges from my book as a writer whose developments in style are neither introspective nor overly preoccupied with Catholicism, but are restlessly concerned instead with exploring the possibility of literary form to produce an agile kind of social critique.

Spark once said that fiction offered her the chance to explore ‘hidden possibilities’. I hope my book can do the same. After all, there’s more than one side to a crystal.

Dr James Bailey’s book, Muriel Spark’s Early Fiction: Literary Subversion and Experiments with Form, will be published next month by Edinburgh University Press.

About the Book

This book presents a detailed critical analysis of a period of significant formal and thematic innovation in Muriel Spark’s literary career. As the first critical study to draw extensively on Spark’s vast archives of correspondence, manuscripts and research, it provides a unique insight into the social contexts and personal concerns that dictated her fiction.

Dr James Bailey is Honorary Research Fellow in English Literature at the University of Sheffield. He is the author of Muriel Spark’s Early Fiction: Literary Subversion and Experiments with Form (Edinburgh University Press, 2021) and co-editor, with Emma Young, of British Women Short Story Writers: The New Woman to Now (Edinburgh University Press, 2016). He now works for Arts Council England.