By Dan Taylor

In October 2020, in the days leading up to the US Presidential Election, over 130 leading historians of fascism signed an open letter. They warned that democracy today is deeply imperilled. It is either ‘withering or in full-scale collapse globally’.

Those were prelapsarian times…

In the weeks and months since, even hardened observers have looked on aghast as a series of shocking events unfolded. The defeated President Trump attempted to usurp the result of the election. Many Americans accepted the bizarre conspiracy of a secret deep state run by Satan-worshipping left-wing paedophiles. And an armed mob bearing confederate flags and anti-Semitic signs broke in and ransacked the US Capitol in an attempt to stop the presidential election results certification, resulting in the deaths of at least five people (and the new-found global celebrity of the ‘QAnon shaman’…).

Such events can shake our faith in democracy at its core. Despots around the world are gloating gleefully at the ‘fragility’ of democracy. Meanwhile, politics in the US, UK, France and elsewhere is becoming increasingly marked by polarisations that seem irreconcilable.

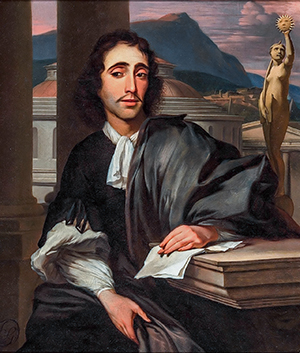

But this is not the first time that democracy has been in trouble. In times like these, we can learn a lot from those who have been in this situation before. In this case, the Enlightenment philosopher Spinoza, who made an impassioned plea for democracy against the backdrop of conflicts in Dutch society between the liberal, wealthy, urban elite and a powerful popular movement to install a religiously conservative monarchy.

Two arguments for democracy

Spinoza’s argument for democracy rests on two claims:

- Democracy is the most natural form of politics for human beings because of our inherently social, cooperative nature

- Democracy is the best system for making decisions because representative assemblies can hear and consider the widest range of informed views.

As Spinoza writes in his Theological–Political Treatise:

The democratic republic … seems to be the most natural and to be that which approaches most closely to the freedom nature bestows on every person. In a democracy, no one transfers their natural right to another in such a way that they are not thereafter consulted but rather to the majority of the whole society of which they are a part. In this way all remain equal as they had been previously, in a state of nature.

Democracy is best of all precisely because it reflects a condition of formal equality between human beings like that we find in nature. No one individual counts more than any other. Moreover, people are far more likely to cooperate and assist each other when each is valued equally, and when each is able to participate and contribute equally. We could call this a naturalistic argument for democracy. It may remind us of Aristotle’s saying that the human being is a ‘political animal’. Sociality and cooperation are essential to our nature.

Protecting democracy from the politics of fear

But such an ideal is by no means easily achieved. The Theological–Political Treatise is alert to the ways in which politically motivated monarchs, despots and demagogues adopt a politics of fear and the trappings of religion to cower the many into giving up their rights to think or vote. That’s why we must preserve and protect democracies: they enable difficult or inconvenient views to be circulated. This allows the most representative range of positions to be considered. We could call this an epistemic argument for democracy: through the unencumbered circulation and communication of ideas, the most credible and rational views will flourish. Spinoza says:

Were it as easy to control people’s minds as to restrain their tongues, every sovereign would rule securely and there would be no oppressive governments. … [but] the purpose of the state is not to turn people from rational beings into beasts or automata, but rather to allow their minds and bodies to develop in their own ways in security and enjoy the free use of reason, and not to participate in conflicts based on hatred, anger or deceit or in malicious disputes with each other. Therefore, the true purpose of the state is in fact freedom.’

For today’s pessimists, Spinoza says that democracy is essential. It teaches us not just how to live together well and make better decisions that represent the interests of all citizens, but precisely because human life is so uncertain and led by the imagination.

Democratic Practice: from the Enlightenment to Trump

The ugliness of modern politics should compel us not to look away, but to attempt to understand the forces that have led to our moment and that separate fear from flourishing. It suggests what we might call a democratic practice. This captured in the words of the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall as ‘trying to enable people to live together, without eating one another and without pretending they are the same’. It’s not always easy.

But democracy also boosts our power of thinking, in understanding other people and reasoning about competing moral and epistemological claims. Without democracy, societies become like ‘deserts’, consumed by fear and loneliness. From equally uncertain times, Spinoza sends a message in a bottle: the desire and promise of democracy is irrepressible, because it is based on what makes us fundamentally human.

Image credits

- ‘US Capitol at Night‘ by John Brighenti, via Flickr. CC BY 2.0.

- ‘The US Capitol Lit Up‘ by John Brighenti, via Flickr. CC BY 2.0.

- ‘Spinoza Nicolas Dings Zwanenburgwal Amsterdam‘ by Brbbl, via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.

- ‘Portrait of a man, thought to be Baruch de Spinoza, attributed to Barend Graat‘ via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

About the author

Dan Taylor is a Lecturer in Social and Political Thought at the Open University. His most recent book is Spinoza and the Politics of Freedom (2021, Edinburgh University Press). He is also the author of Island Story: Journeying Through Unfamiliar Britain (Repeater Books, 2016), shortlisted for the Orwell Prize 2017, and Negative Capitalism: Cynicism in the Neoliberal Era (Zero Books, 2013).

Did you enjoy ‘Spinoza and democracy in peril’? Read more in the book, Spinoza and the Politics of Freedom by Dan Taylor.

You might also like…

- The world of Spinoza’s Theological–Political Treatise by Dan Taylor

- 5 things you never knew about Spinoza by Tatiana Reznichenko