By Dan Taylor

Baruch Spinoza’s Theological–Political Treatise, published anonymously in 1670, quickly turned Europe upside-down. Dismissed by one contemporary as a book ‘forged in hell by the Devil himself’, it argued that for societies to endure conflict and flourish, they must champion free speech and independent thought, religious toleration and democracy.

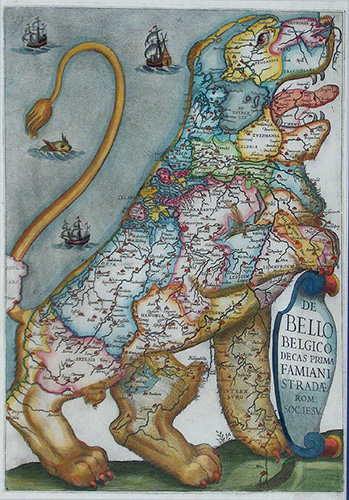

Leo Belgicus

The 17th century saw what we now think of as the Dutch Golden Age – a time of peace, splendour and wealth. The Low Countries had risen in revolt against Spanish rule from 1566. The Northern provinces spectacularly gained formal independence from Europe’s then-leading superpower in 1648. This left the Catholic south (modern-day Belgium and Luxembourg) under Spanish dominion.

From the outset, an unusual liberalism marked the Dutch United Provinces. Freedom of worship extended not to just to Protestants but to Non-Conformist sects like the Socinians (who believed that Christ was a man, not divine, and rejected the Trinity) and provided refuge to Iberia’s Sephardic Jews. Yet beneath this thin veneer of toleration was a loathing of Catholicism. Anything seen to undermine a strict Calvinist interpretation of public morals was suspicious.

Moreover, while the Provinces were formally a republic, its de facto head of state was the first-born son of the House of Orange. This tension between a federal republic and monarchy threatened to submerge the country into civil war. Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, architect of Dutch independence, was executed after falling foul of Maurice, Prince of Orange, and his conservative supporters. Could the same happen again?

The ‘Golden Age’

Overthrowing Europe’s maritime giant was an expensive business. Spanish control of the Mediterranean and Atlantic meant that the Dutch had to find new trading routes and partners. They followed the secret trade routes of Portuguese navigators like Vasco de Gama, circling the Cape to reach Mughal India, China, Japan and the “Spice Islands” (now Indonesia). Oldenbarnevelt founded the Dutch East India Company in 1602, while the Dutch West India Company briefly controlled the lucrative sugar plantations of Brazil. Luxury goods returned on Dutch galleons: gems and ceramics, coffee and tea, cotton, silk, silver and tobacco. Spinoza’s father Michael imported exotic dried fruit to his warehouse in Amsterdam, which he inherited before its bankruptcy.

Fashions transformed. Colourful cottons, velvet and lace superseded heavy wools. New public spaced formed around the consumption of coffee. Calvinist pastors muttered about the corruption of riches. A new motif in Dutch art, those bittersweet bowls of decaying fruit and memento mori, reminded viewers of their mortality.

But who would risk financing such ventures? Many Dutch vessels did not return, captured, killed or lost at sea. The Dutch developed a second innovation that would transform modern Europe: the joint-stock company. Investors would speculate and potentially gain vast returns on risky investments. A new kind of credit-based capitalism boomed, occasionally disrupted by speculation bubbles like Tulip Mania.

Amsterdam flourished. Philosophers from across Europe, like Descartes and Locke, gathered here to pursue their work, enjoying the relative freedom to publish new ideas unfettered of censorship. Scientists like Antonie van Leeuwenhoek and Christiaan Huygens developed cutting-edge microscopes and telescopes, bringing new worlds into view (the latter corresponding with Spinoza, who was also a lens-grinder). Neighbours like England belatedly scrambled to secure their own colonial trade-routes in India and Africa. Modern Europe was coming into view.

Slavery and inequality

Of course, our modern image is deceptive – this ‘Golden Age’ was, in part, funded by slavery. The short-lived Dutch Colony of Brazil, captured from the Portuguese, was based on the most vicious enslavement of the indigenous Tupinambá and the Angolese, kidnapped and transported across the ocean.

And the distribution of this ill-gotten booming wealth was far from equal. Resentment was growing towards the seemingly out-of-touch liberal elite; too busy enjoying their metropolitan luxuries to focus on the serious work of protecting the country from powerful enemies within and without. On the streets, a particularly zealous form of Calvinism began to gain influence; one that articulated people’s fears and grievances through a restrictive and intolerant religious lens. Conflicts brewed between wealthy urban merchants and a popular movement to install a religiously conservative monarchy. The ‘Golden Age’ was disintegrating.

Caute

For Spinoza, already ejected from Amsterdam’s Jewish community for his unconventional views on God, all this was deeply concerning. Legendary reports tell that he had already been subject to an assassination attempt as a young man. An unknown assailant attempted to stab him outside the synagogue or theatre, though the blade only pierced his cloak. Spinoza lived by a slogan he wore on a signet ring: caute (caution).

But, sooner or later, caution becomes timidity; inaction leads to the triumph of barbarism. In the late 1660s, as his friends were being arrested and imprisoned for publishing independent-minded philosophy, Spinoza put aside his work on abstract metaphysics. Only free democracy could overcome these crises.

Someone needed to publicly defend the freedom of philosophy to examine the laws of nature unencumbered by fanatical repression. Someone needed to champion democracy, despite all its difficulties and fragility, in the face of a growing movement to install dictatorship. Someone needed to examine the basis of biblical scripture, prophetic revelation and miracles that formed the bases of almost all public education, morality and claims to political legitimacy.

What exactly was the knowledge claimed by the prophets? What constituted a miracle? Who had written and organised the books of the Bible, and to what ends? What, by nature, does the flourishing of human life consist of? But these were difficult and dangerous questions to ask.

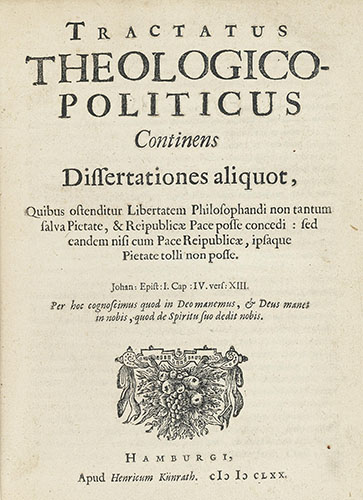

The Theological-Political Treatise was published under a fake imprint in 1670. The identity of its audacious author was not discovered for some years. That man was not the Devil, but Baruch Spinoza.

Image credits

- Famiano Strada, De Bello Belgico decas prima. Public domain. Via Wikimedia Commons.

- Jan Brueghel the Younger, Satire on Tulip Mania, c. 1640. Public domain. Via Wikimedia Commons.

- Jan Luyken, The Destruction of Jan de Baen’s Allegory on Cornelis de Witt (on May 13 or June 29, 1672) in the City of Dordrecht. Public domain. Via Frans Grijzenhout, ‘Between Memory and Amnesia: The Posthumous Portraits of Johan and Cornelis de Witt‘, Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 7:1 (Winter 2015) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2015.7.1.4.

- Title page of Benedictus de Spinoza – Tractatus theologico-politicus. Public domain. Via Wikimedia Commons.

About the author

Dan Taylor is a Lecturer in Social and Political Thought at the Open University. His most recent book is Spinoza and the Politics of Freedom (2021, Edinburgh University Press). He is also the author of Island Story: Journeying Through Unfamiliar Britain (Repeater Books, 2016), shortlisted for the Orwell Prize 2017, and Negative Capitalism: Cynicism in the Neoliberal Era (Zero Books, 2013).

Did you enjoy ‘The world of Spinoza’s Theological–Political Treatise’? Read more in the book, Spinoza and the Politics of Freedom by Dan Taylor.

You might also like…

- 5 things you never knew about Spinoza by Tatiana Reznichenko