By Stanley Gontarski

American outlier writer, William S. Burroughs, was a creative force, as a writer in his own right, and as a cultural theorist, particularly his anticipation of what we now regularly call “a society of control” or “a surveillance culture,” and, moreover, as a textual embodiment, as well.

Burroughs was as much a media and performance artist as he was a traditional literary figure, what we have generally called a writer, or novelist, although he lauded those latter categories as he offered critiques of “thought control” by a media that strips us of volition and, more generally, of a “control society.”

In his lectures on Michel Foucault delivered at the Université de Paris VIII in the 1980s, Gilles Deleuze details Burroughs’s influence on both philosophers with his critique of our “control societies,” a term they adopt from him. Further, in Deleuze’s lectures On Cinema at La Fémis (Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Métiers de l’Image et du Son) in 1987 he notes: “There have been, of course, various remnants of disciplinary societies for years, but we already know we are in societies of a different type that should be called, using Burroughs’ term—and Foucault had a very deep admiration for Burroughs—control societies.”

Burroughs and his work were very much a product of and a commentary on his time. Even if as a cultural Outsider, his vision of a dystopian future, his discourse of repetitions, his stochastic materiality, his critiques of the politics of drugs and surveillance, his foregrounding of what we today call queer theory, his media experiments, in short, his art, are sustainable beyond his time and beyond his traditional standing as the Priest of the Beat generation, as a significant cultural agitator in the ‘60s counterculture and anti-war protests, as an icon of the punk and alt rock of the 70s and 80s, through to our multi-media age and society of control, the contemporary critique of which Burroughs helped shape.

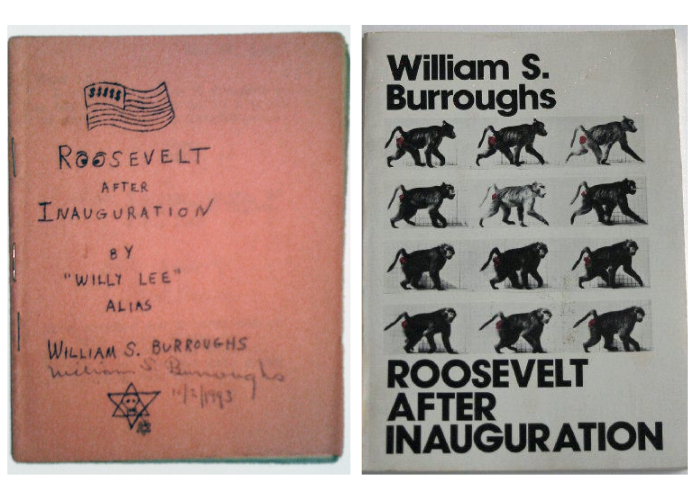

With very few direct intersection with continental philosophy and the developments of critical theory he seems, nonetheless, to have developed parallel lines of thought and strategies of resistance, which Foucault and Deleuze recognized and credited. Their critical intersection came at the Schizo-Culture conference at Columbia University in 1975, after which the conference organizers, particularly Sylvère Lotringer, followed up with a Nova Convention designed as a tribute to Burroughs and at which, on 30 November of 1978, Burroughs delivered what the organizers called a Keynote Commentary, “Roosevelt after Inauguration,” a reprise of his 1964 publication that was part of the “Mimeograph revolution” and so part of the weaponizing of publishing and the material aesthetics of the 1960s and ‘70s. At least one critic and book collector has said that “Roosevelt was a fuck you to mainstream publishing, City Lights, and the United States government,” even as the work was subsequently published by City Lights Books. [1]

That rowdy Nova Convention featured not only Burroughs but other post-‘60s outsider artists responding, in one way or another, to his work, all of which highlighted how much of that work was performative and so potentially fleeting. Continuous with Burroughs’s preoccupation with media, however, was the growth of media technology and theory and so such astonishing performances have been technologically preserved, including much of the Nova Convention itself, particularly Burroughs’s “What the Nova Convention Is All About.”

These critiques from the 1970s were and currently remain inseparable from Burroughs’ emergence as a performance artist, such embodiment of his art readily available for consumption amid our own image-obsessed Electronic Revolution, to borrow a Burroughs title, or updated as Guattari’s “post-mediatic revolution” in his Soft Subversions.

The products of this period are currently being re-circulated through commercial outlets and through multiple open access formats today. This suggests , and possibly confirms that Burroughs, whom many another Outsider has called “The Priest,” (for example, Kurt Cobain during their 1993 collaboration) the artist who also described himself as a “cosmonaut of inner space” and “a technician of consciousness,” this Dystopic Modernist author, visionary science fiction writer and aesthetic weapons maker, was one of the major media artists, social critics, cultural theorists, and literary figures, not only of his but of our “postpersonal” time.

[1] Jed Birmingham (2016). “#12: Roosevelt after Inauguration.” Reality Studio. New York: Fuck You Press, 1964. First edition. 24mo, [12] pp, mimeographed from typescript and drawing.

Banner image of William S. Burroughs by Christiaan Tonnis under the Creative Commons License.

Read Stanley Gontarski’s full article, ‘Weaponised Aesthetics and Dystopian Modernism: Cut-ups, Playbacks, Pick-ups and the ‘Limits of Control’ from Burroughs to Deleuze‘ from the latest issue of Deleuze and Guattari Studies.

A bold and genuinely interdisciplinary journal, Deleuze and Guattari Studies does not limit itself to any one field: it is neither a philosophy journal, nor a literature journal, nor a cultural studies journal, but all three and more. Articles explore the work of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, as well as critical reviews of the growing field, new translations and annotated bibliographies. Sign up for Table of Contents alerts, find out how to subscribe, or recommend to your library.