By Julian Petley and Andrew Roberts

Catch up with Part One of Culture Wars, Talking Pictures and the Telegraph

For Heffer, ‘the lesson of Talking Pictures is clear. It portrays the England millions of us wish we still lived in’. But this is simply to ignore the fact that various films shown on Talking Pictures explicitly deal with different kinds of ‘them’ – for example, 1959’s Sapphire, featuring the late, Bermudan-born Earl Cameron. It is one of the actor’s finest performances, not least for the moment in which he resignedly telling a police Superintendent: ‘There’s no assurance for me and my kind’. Can this really be the world to which Heffer wants to return?

It’s also interesting that Heffer sings the praises of Hammer Studios, since various studies have shown that, when these films were first released, the mainstream critics absolutely loathed them, complaining bitterly that their copious blood-letting was a far cry from the alleged restraint and subtle suggestion of the Universal classics. (Of course, the British critics hated them too at the time of their release). Nor are there any soothing qualities in 1965’s The Nanny, especially the scene of a GP berating the title character after the death of her daughter from a back-street abortion. Talking Pictures has also screened Quatermass and the Pit, which ends so memorably in murderous mob violence and the wreckage of London – and maybe of the entirety of civilisation

One somehow feels that had Heffer been writing during either the Universal or Hammer eras, he too would not have been exactly an admirer. It is, by the way, particularly unfortunate (although presumably not the author’s fault) that the picture which illustrates Heffer’s article is utterly inappropriate. Although it’s not credited, this is from Dracula AD 1972, precisely at the point at which Hammer was injecting more sex and violence into their films in the wake of the ‘Swinging Sixties’, an era with which one doubts that Heffer has very much sympathy.

One of the many attractions of Talking Pictures is its array of archive television Their output has included major attractions from ITV’s back-catalogue, such as Gideon’s Way, Callan and Public Eye. Few viewers of a certain age would expect Heffer-style reassurance from the last two series, but the first one too can be surprisingly harsh, for all its gentlemanly detectives and bell-clanging Wolseley squad cars. We talked to Matthew Sweet about this and he commented:

Talking Pictures TV looks like it offers the kind of programming approved for broadcast just before the outbreak of nuclear war – soothing images of the British past. Paradoxically, though, the material rarely provides an opportunity to doze off on the Dormeo mattress of history. In the past few months I have watched Callan episodes of uncompromising bleakness, I have seen Gideon’s Way deal with posh thugs and domestic tyrants, I have been taken aback by how TV drama of the 50s and 60s saw the middle-class marriage as a theatre of verbal and physical violence. A lot of it is compellingly unpretty.

ITC filmed Gideon’s Way between 1964 and 1966, and while certain episodes now appear engagingly ham-fisted (especially when they attempt to deal with ‘youth culture’) others are resoundingly grim. Thus The Prowler focuses on a mentally disturbed young man who cuts women’s hair under the cover of darkness, while children are beaten by their own mothers in Big Fish, Little Fish. Meanwhile, for those familiar with only the later colour editions of Callan, the surviving black and white shows are a revelation, with a PTSD-afflicted protagonist often destroying lives in the name of Queen and Country.

But for sheer, relentless despair, little can equal The Man Who Said Sorry, a 1972 episode of Public Eye. To say that Paul Rogers gives one of the best performances in the history of British television is no hyperbole: for almost 50 minutes one us in the presence of collapsing hopes and self-identity. Perhaps the character of Raymond Clemens once believed in the mythology of the stoic middle-class Englishman but now his delusions are dissipating by the minute.

Heffer also praises the ITV series The Adventures of Robin Hood, which starred Richard Greene. But as any fule kno (to reference the Nigel Molesworth books, which are surely Heffer favourites), and as is illustrated in the film Fellow Traveller, this was created by the producer Hannah Weinstein partly in order to enable the commissioning of scripts by blacklisted American writers. Among these were Ring Lardner Jr., Waldo Salt, Robert Lees, and Adrian Scott (all writing under pseudonyms). Howard Koch, who was also blacklisted, served for a while as the series’ script editor. According to Heffer, Greene was ‘to millions of us of a certain age, really was Robin Hood’, but he was also a proto-socialist hero of whom one would have thought that Heffer would strongly disapprove. However, here as elsewhere in Heffer’s Talking Pictures pantheon, nostalgia adds considerable, if highly distorting, enchantment to the view.

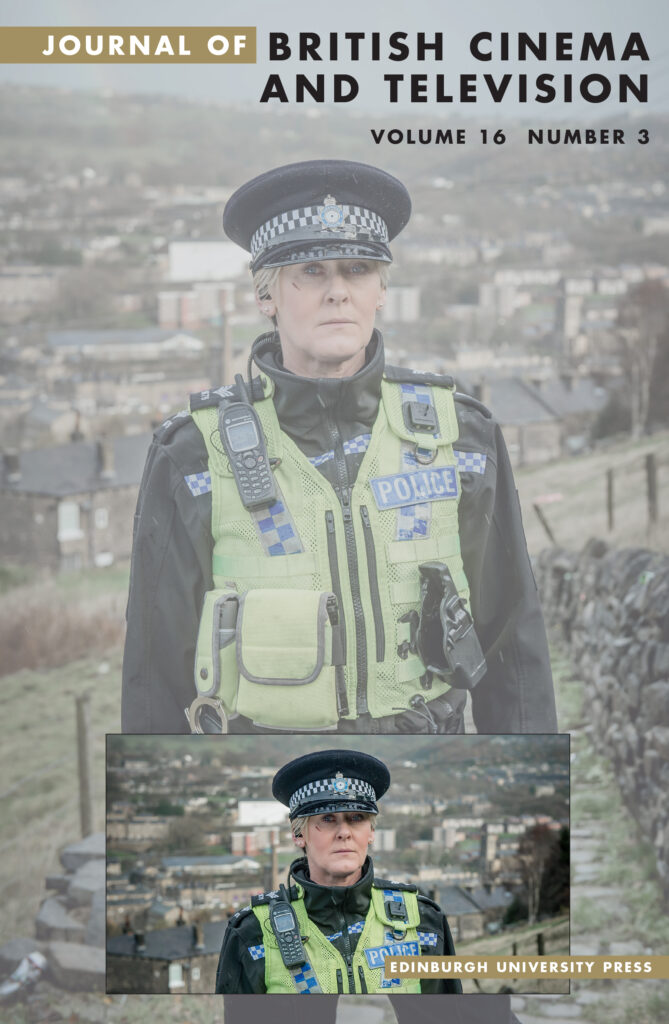

The Journal of British Cinema and Television is indispensable for anyone seriously interested in British cinema and television. Themed issues alternate with general issues, and each issue contains a wide range of articles that encourage debate. Find out more about the journal, how to subscribe, and how to recommend to your library. Sign up for Table of Contents alerts so you never miss an issue.

Gideon’s Way was a hard-hitting show for its time – there’s one episode that deals with homosexuality, and another in which a murderer gets away with it. There’s also “Morna,” with its flashbacking structure and weird resemblance to Twin Peaks.