Thanksgiving Model Buildings

An article published in The Lady’s Newspaper in 1851 makes an explicit connection between creative production – in this case writing – and its effect on architecture. ‘The painfully true pages of Mr. Mayhew’s “London Labour and the London Poor”, the anonymous author comments, ‘give a startling yet true description [of the] crowded houses of the poor.’ The author claims that Mayhew’s contributions to the Morning Chronicle documenting the lives of the urban poor and labouring classes, collected in three volumes the year of this article’s publication, had called public attention to necessity of adjustments in housing design to ensure ‘wholesome air and plenty of water.’ While the impetus for such adjustments may have had its origins in the substandard homes of the city’s impoverished areas, the author explains that in the ‘dwellings of persons even in the upper and middle classes[,] the system of building and ventilation requires for the purposes of health a very considerable alteration.’

Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor (1851) – to which may be added a flurry of social investigative texts including Fredrich Engels’s The Condition of the Working Classes in England (1844) – is not connected to one particular building design but instead to an architectural and social movement. The model dwellings movement, which began roughly a mid-century, gave rise to a number of associations that used shareholder investment to purchase land and construct improved dwellings for the working poor and labouring classes. Although the buildings of some model dwellings companies remain an part of the city’s fabric today, for instance those of the Peabody Trust, there were approximately 30 such organisations operating in London the latter half of the century.

The Lady’s Newspaper reports on the healthful achievements one of the earliest model dwellings companies: the Society for Improving the Condition of the Labouring Classes. The Society financed the construction of the Thanksgiving Model Buildings at Portpool Lane near Grays Inn Road, allegedly ‘one of the worst neighbourhoods in London.’ The Thanksgiving Model Buildings, designed by Henry Roberts and completed in 1850, provided accommodation for 20 families, but also offered – in rather astonishing ratio – accommodation for 128 single women. The rooms for single women were each furnished with two iron beds that could be folded up during the day, a table, washstand, fireplace, and cupboard. The rooms were particularly suited, it seems, to needlewomen who may have worked long hours in their lodgings. Rooms were 2s. per week, but with two beds could be shared and thus cost only 1s. per week for each woman.

The women were accommodated separate to the families in a four-storey building was divided by a central open staircase: an important factor for ventilation. Residents accessed their rooms by a corridor that stretched the length of the building on either side, and which also served as a central lobby. The use of hollow bricks helped to fire-proof the structure, and based on the published floorplan, each room seems to have had a window into a specific ‘area for light and ventilation.’

Such provision of such ‘private and wholesome’ accommodation for single women – especially many of whom may have had no guaranteed income – was radical both in idea and design. In fact, it would be more than twenty years before Lady Mary Fielding would establish the Working Ladies’ Guild and offer purpose-built accommodation for ‘genteel poor’ women at Oakley Street in Chelsea.

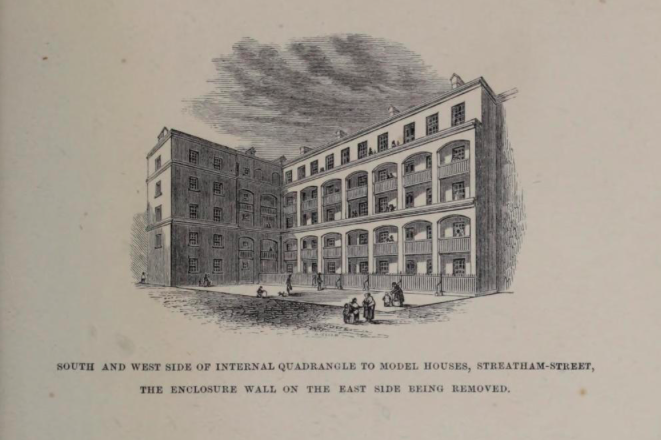

Although the Society for Improving the Conditions of the Labouring Classes was not dedicated to providing housing specifically for single women, it is possible to consider the radical nature of even its designs for family housing at this time. In 1849, Henry Roberts designed another building for the Society that was built at Streatham Street in Bloomsbury, and which also used innovative systems to maximise ventilation. For instance, Roberts dispensed entirely with separate staircases and internal communication and instead employed a series of external walkways arranged around a quadrangle system support by a series of arcades.

In materials, Roberts made use of slate floors, iron beams and hollow bricks for fireproofing. And although the Streatham Street Dwellings were designed and built specifically for families – the long title of the building was ‘Streatham Street Model Houses for Families’ – its design aimed to synthesise private dwelling rooms with shared facilities and communal areas. It was in practice, however, that residents would have to negotiate such boundaries between public and private space. For instance, The Lady’s Newspaper anticipates that ‘unnecessary regulations around entrance to the building at night will prove unpopular and make residents think ‘otherwise than they are paying an honest value for their dwellings.’ Many industries, the author points out, require unsocial hours and such policies would make the buildings entirely useless to trades such as printing. The Lady’s Newspaper recommends that, instead, each person is furnished with a key to the building’s entrance.

Art for Feminist Cities

Many of London’s ‘lofty’ model dwellings were, in fact, inspired by Edinburgh’s walk-up tenements, some of which date as early as the seventeenth century. Despite this early antecedent, London’s nineteenth-century model dwellings movement – and residential design in the period more generally – remains radical for the dynamic political and social shifts around class and gender that contextualise these projects, and to which they respond.

In Leslie Kern’s remarkable new book Feminist City, she imagines the ways that a city might look and operate differently if it were designed along feminist principles. How might cities operate to reduce, rather than further entrench, social inequalities? The forms of radical housing that Home and Identity considers, including Model Dwellings Corporations, often attempted to address this important and enduring question – even if the answer wasn’t always easy to achieve.

About the Author

Lisa C. Robertson is Lecturer in Women’s and Gender Studies at Acadia University in Wolfville, Nova Scotia. She is co-editor of Margaret Harkness: Writing Social Engagement, 1880–1921 (MUP, 2019). You can find out more about Lisa’s new book Home and Identity in Nineteenth-Century Literary London on our website.