By Nancy Lindisfarne-Tapper

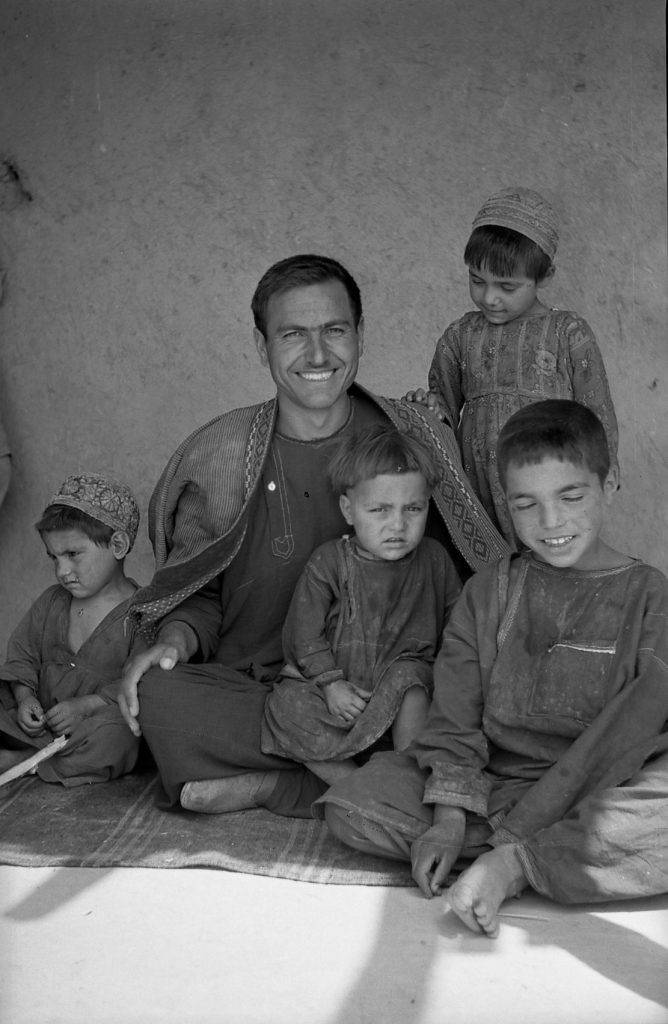

In 1971 and 1972 Richard Tapper and I lived with Afghan villagers for nearly a year. The Piruzai, some 200 families, lived in two small settlements near the town of Sar-e Pol in northern Afghanistan. They were Pashtu-speakers, pastoralists and peasant farmers, poor people, working very hard to survive in a vicious feudal system.

The people, the setting, and even the division of labour between Richard and myself seemed to conform to every stereotype about the Middle East. There were veiled women, men on horseback, camel caravans, stunning scenery and dramatic lives. These were stereotypes shared by the Afghan officials, politicians and urban professionals we met in Kabul. But the people we met were not two dimensional.

They were warm, funny, clear-thinking and tough. They understood we were doing research – anthropology – insanshenasi – and they wanted to help us ‘write a book’. They wanted their words to be heard and written down. Living with the Piruzai was an immense privilege and our obligation to tell the story of the Piruzai is on-going.

Richard and I, separately and together, have written extensively about the Piruzai, including an ethnographic monograph, my Bartered Brides: Politics, Gender and Marriage in an Afghan Tribal Society (Cambridge: CUP, 1991). But we always knew their humanity, and the great depths to their lives, was something academic writing could never fully reach.

To this end, Richard took on the immense task of retranslating more than 100 hours of tape recordings so the Piruzai could tell their story in their own words. ‘Maryam’s Story: An Ethnographic Memoir‘ (published this spring in Afghanistan 3.1, 2020: 27-47) is the first fruit of that labour. A book, Afghan Village Voices: Stories from a Tribal Community by Richard Tapper, with Nancy Lindisfarne-Tapper, will be appearing with I.B. Tauris early this summer. It is an account of Afghanistan at a time of peace, told by people whose voices have rarely been heard.

And now it is my turn to find another way of writing about the Piruzai. This is how I have begun the story of our fieldwork.

Meeting Sati

I met Sati, my first friend, and a good friend right through fieldwork, in Hajji Mulk’s camp in the spring pastures. There were five black-tented households and a white canvas guest tent strung along the side of a shallow valley. The steppe was carpeted, emerald, lush and velvety with grass. We’d been invited to stay in the camp.

‘You go and talk to the women’, Kuk, Hajji Mulk’s son, tells me. Kuk is his nick-name, his real name is Mastu Khan. And I do what Kuk says that very first day.

There are a whole gang of women there, all working together to sew a suit of clothes for one of the hired shepherds, a young man they nicknamed, ‘Pahlevan – Strongman’. They clearly like him. He’s from a Persian-speaking group living in a very poor, very remote valley in the centre of the country. The clothes are a present from the family for Nowruz, the Persian New Year.

The women are comfortable with each other, and it is easy to be with them. They are patient with me, speaking Persian to help me along, repeating themselves two and three times to make sure I understand, then telling me to get busy and learn Pashtu as soon as I can. I am the first foreigner they’ve ever met.

Sati is not the oldest, but she is bold. Right away she tells me she and Tor Mohammad have been married twelve years, and have no children.

‘I haven’t been to a doctor or to a shrine’, she says, and her face falls with grief. There are tears in her eyes.

She tells me Tor Mohammad talks about taking a second wife, ‘But he hasn’t done it. Not in all this time.’

Then Tor Jan, as I know to call him, turns up and drops an armful of brushwood outside the tent. Compared with that of Hajji Mulk which can house a multitude, Sati and Tor Jan’s tent is small. It is made of big pieces of woven goat-hair cloth and is some 25 feet long and 15 feet wide. It is raining outside and inside there is the finest mist which dampens the paper of my little notebook where I’m writing down new words.

Tor Jan sits down next to Sati, and they touch hands and smile at each other as they talk to me. They’re first cousins, they tell me. Sati calls him Tor Mohammad.

‘It’s his proper name’, she tells me when I ask. ‘If you love your husband you call him by his real name’, she says, then pauses and looks at me and decides to try out a joke. ‘If you don’t love him, or you are angry with him, you call him ‘Hey!’

I am so pleased that I get it. All the women join in, laughing, and I can almost see Tor Jan, who is very dark skinned, blush.

Sati is not yet thirty, but she looks worn. Her mother is visiting, with three of Sati’s younger sisters and a baby brother, her mother’s first son, at her breast. The little boy is ten months old, and petted and pampered outrageously. He wears some twenty amulets and is clearly much wanted. Everybody plays with him.

Satis’s mum strikes me as a sensible, intelligent woman, and I can see she is well-respected by the others.

‘Is your mother alive?’, she asks me.

‘Yes, thank god, yes.’

‘That’s good’, she says, ‘But you must be very dik, very sad’, and she touches my hand. ‘She’s in America, ney? Your heart must be burning when she is so far away.’

Sati’s little sisters have settled in with their big sister for some days at least. The oldest, Zara, helps with milking the sheep, but without much effect. She is only ten. Even the smallest, four or five-years old, is perfectly happy away from home. I watch them playing nicely with the other kids in the camp. Sati clearly enjoys having them around. The little girls, the grown women, all dress almost alike, same hair, same embroidered hats and the same puranay veils with fancy borders on top.

All through the day we talk. There was a lot of talk about clothes, about henna and kohl. I get out my little make-up bag, and they try the lipstick, the powder and Nivea cream. They’re very keen on being white-skinned. Matelha, one of Hajji Mulk’s daughters-in-law, brags that she is very white-skinned. ‘And Matelha has a long white neck’, someone adds, ‘wearing black sets it off best’.

Kuk’s son, Salaam Khan is around. Everyone calls him diwana, mad. They say he’s a rogue. He’s seven years old and circumcised, but he never wears trousers. Not because he doesn’t have any, but because he won’t – he refuses in his willful way. He tells us all he saw his father and mother kiss each other last night. And everyone laughs, including Hajji Bakhtawar, his granny.

I already like these people lots.

By Nancy Lindisfarne-Tapper

31st May, 2020 from fieldnotes, 20th March, 1971; 29th Hud, 1348.

Nancy and Richard’s article, ‘Maryam’s story: An ethnographic memoir‘ appears in Volume 3, Issue 1 of Afghanistan, the journal of the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies. Find out more about the journal, how to subscribe and recommend to your library.