Read Laura Mayne’s overview of the new book Sixties British Cinema Reconsidered, which re-evaluates a critically neglected period in British film history.

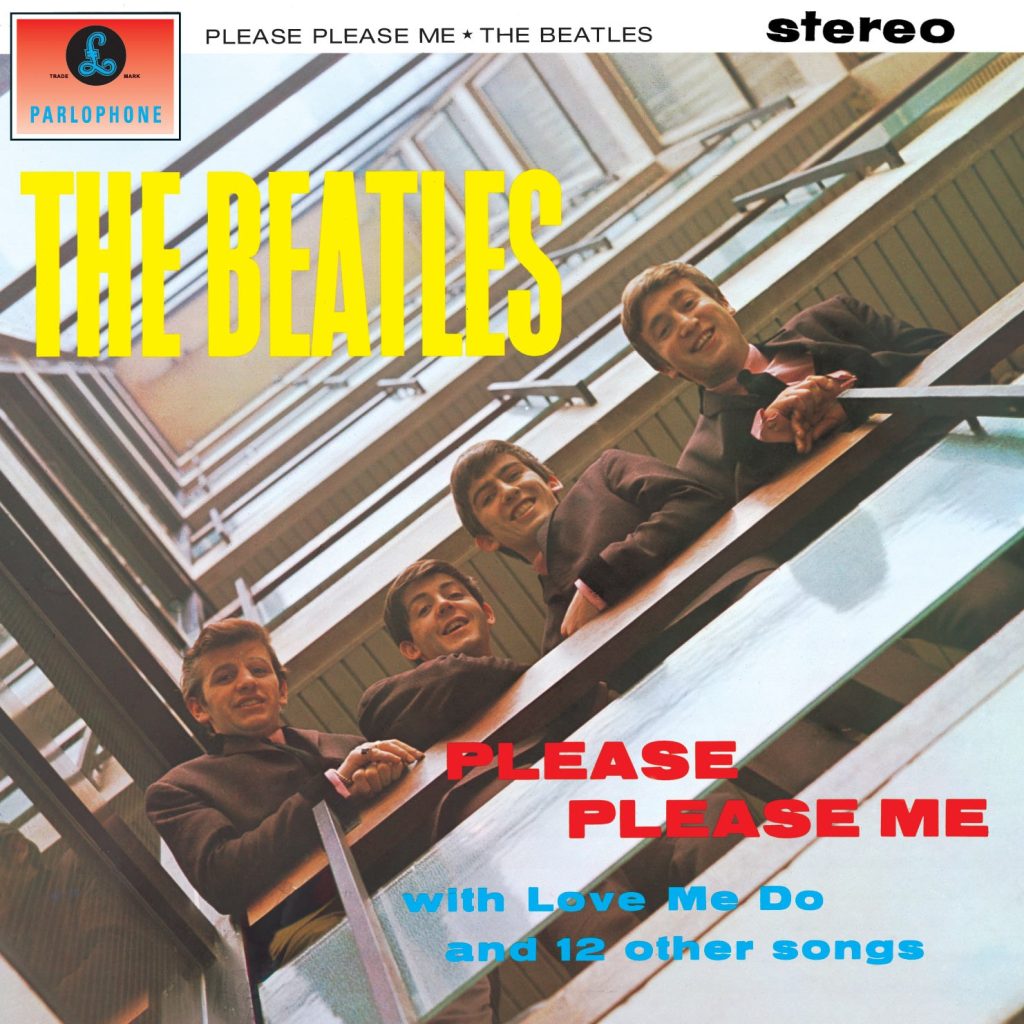

Has here been any decade more inconsistent in the public imagination than the 1960s? Lived recollections of the era are often intertwined with popular culture and the changing media landscape. As the Philip Larkin poem goes, ‘sexual intercourse began in 1963… Between the end of the “Chatterley” ban/And the Beatles’ first LP.’ The lifting of the obscenity ban on Lady Chatterly’s Lover in 1960 symbolised a move toward a more permissive society, and this was also the era when rock and pop music exploded in ways that would come to define a generation. But for many residents of the British Isles, day-to-day life continued much as it had before, and this is why people who lived through the 1960s often report having two sets of memories: the humdrum realities of daily life in Romsey and the colourful, swinging interpretations that circulated in media and popular culture.

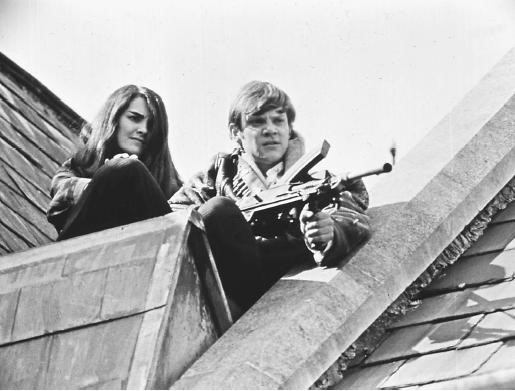

In an era characterised by tradition as much as by transformation, it’s no surprise that national cinema was a complicated fusion of the old and the new. For example, Lindsey Anderson’s If…. (1968), a tale of anarchic youth run amok in a British public school, worked loose old assumptions about class and British society. But we should also bear in mind that the Carry On… series of comedy films topped the British box office every single year of the 1960s, and this was a sign that the old tradition of British seaside postcard humour and music hall bawdiness remained a key part of British national culture.

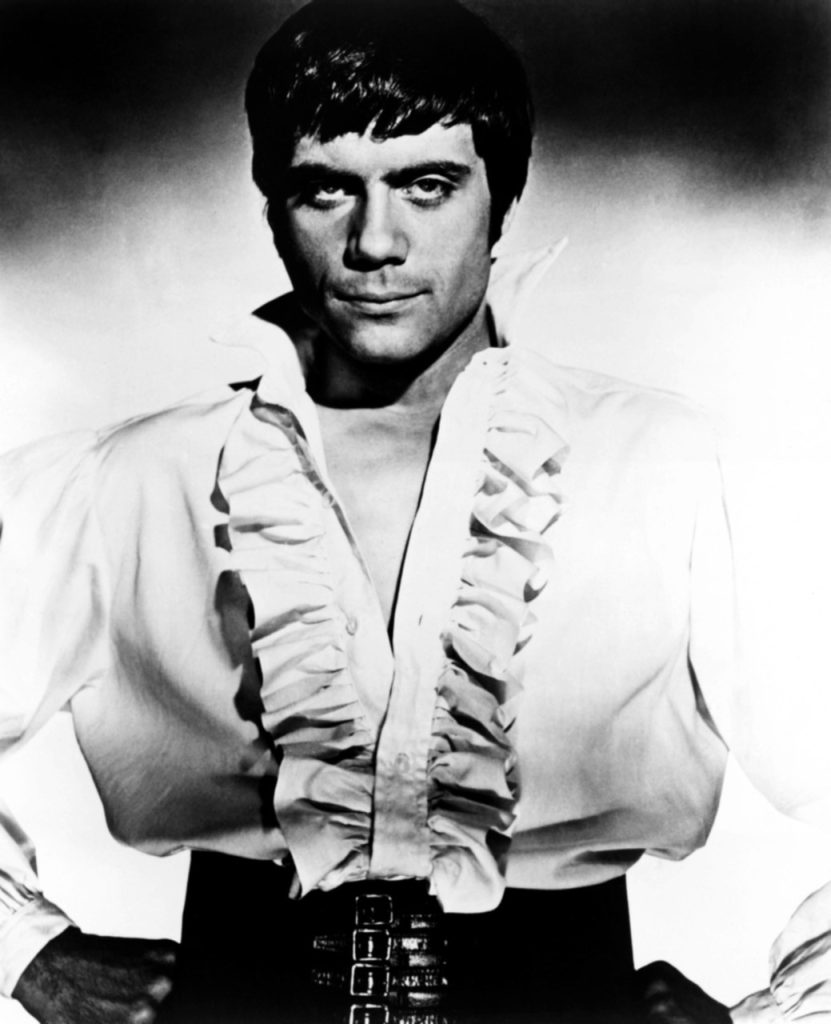

This historical dissonance is explored in a new edited collection, Sixties British Cinema Reconsidered, which goes beyond existing accounts of the era as well as providing a multiplicity of new perspectives on familiar stories. The first section, ‘Stars and Stardom’, appraises key cultural figures of the decade. Margherita Sprio explores the career of Carol White, the so-called ‘Battersea Bardot’ who rose to prominence in Ken Loach’s Cathy Come Home (1966) and Poor Cow (1968). Caroline Langhorst focuses on masculinity and stardom in her case study of the raw, Byronesque performances of Oliver Reed, and Andrew Spicer also discusses performance in his chapter on 60s male stars who were celebrated for their particular brands of working-class masculinity: Sean Connery, Michael Caine Albert Finney and Terence Stamp.

In section 2, ‘Creative Collaboration’, the authors go beyond auteurist film histories that are often characterised by a focus on directors and cinematographers. David Cairns looks at the often-marginalised work of the screenwriter in his study of Help! (1965) scriptwriter Charles Wood while Dave Forrest and Sue Vice focus on the process of adaptation in their chapter on Kes and the work of novelist Barry Hines. Vicky Lowe offers a case study of the work of Jocelyn Herbert, production designer on If…., while Llewella Chapman takes us on a tour of the obscure but fascinating world of film finance in her archival study of Joseph Losey’s Figures in a Landscape (1969).

In section 3, ‘Style and Genre’, the tension between cultural transformation and tradition is evident in chapters on such diverse topics as Hammer Films and censorship (Paul Frith) Cold War films (Steven Roberts) and sixties corporate fantasies (Carolyn Rickard), while Virginie Selavy focuses on late 1960s counterculture in the low budget horror films of Michael Reeves. The clash between old and new is even more evident in section 4: ‘Cultural Transformations’. From British Naval films (Mark Fryers) to drug-influenced psychedelic light shows (Sophia Satchell-Baeza) the 1960s was an era of diverse and conflicting interactions between the establishment, subcultural diversity and countercultural expression. Finally, given the racial tensions rippling across British society during this decade, it is surprising how seldom these tensions actually manifested in the national cinema of the era (Flame in the Streets [1961] and To Sir With Love [1967] are notable exceptions), and Phillip Drummond focuses on how issues of race and identity played out across British national cinema.

By Laura Mayne

Laura Mayne is an Associate Lecturer at the University of York. Her research specialism is in post-war British cinema with an emphasis on industrial history, institutional practices and production cultures, and she has published widely on these subjects. She is currently working on her first monograph, titled Slumdogs and Millionaires: The Story of Film4.

With perspectives and insights from established scholars and new critical voices, Sixties British Cinema Reconsidered draws on under-explored archival resources to explore four key research areas: stars and stardom; creative collaborations in filmmaking; developments in genre and film style; and how the cinema of the period both responded and contributed to social and cultural transformation in the 1960s.

Find out more about Sixties British Cinema Reconsidered