How do authors think about characters, and how might an author’s creative process affect how those characters are invented? Robert Louis Stevenson, who had a lot to say about the relation between author and character, fluctuated between two different methods of character creation over his career.

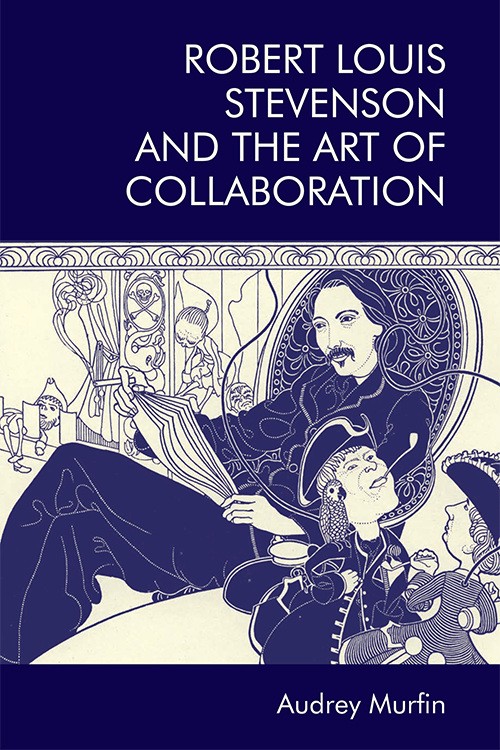

On the one hand, Stevenson conceived of characters as puppets, artificial creations who were self-consciously fictional and whose purpose was to advance the story. In “A Gossip on Romance,” Stevenson celebrates the self-conscious artifice of character creation in the Arabian Nights: “No human face or voice greets us among that wooden crowd of kings and genies, sorcerers and beggarmen.” It is also the method represented on the cover of my book, in an image from E. R. Herman taken from a 20th-century edition of Stevenson’s Fables. Herman’s illustration of the Stevenson fable “The Persons of the Tale” depicts the more playful side of Stevenson’s attitude towards his characters. In this story, “After the 32nd chapter of Treasure Island two of the puppets strolled out to have a pipe before business should begin again.” As Long John Silver and Captain Smollett from Treasure Island argue about whom the author likes more, Long John ruefully states, “’There’s no call to be angry with me in earnest. I’m only a chara’ter in a story. I don’t really exist.” (4) In the foreground of Herman’s drawing of this scene, the wooden characters don’t even look at each other but gaze blankly at the sky. A wire extending from each character’s back leads snakingly back to Stevenson, who lounges behind, smoking contentedly. Behind him an array of other puppets slump, ready to be called into use.

But this mode of creation didn’t lend itself to the kind of realistic depictions of character that had been the prominent mode of the Victorian period, and as Stevenson’s style matured out of fantasies like Treasure Island towards more political and realistic work, his method of character creation had to change. The frank avowal that characters didn’t exist, but were mere tools in an author’s toolbox, was out of step with the decree, made by Stevenson’s friend Henry James, that novelists ought not to “give themselves away” by admitting the fictional nature of their projects. Stevenson used another method too, which was to base his fictional characters on real people. This new method enabled to him to collaborate more easily with his stepson, Lloyd Osbourne, to whom he would say “make him So and so.”[i] (Letters 8: 364). (In fact, Long John Silver was based on his friend W. E. Henley, but it was a very loose characterisation.) More realistic mimicries included Stevenson’s friend, the artist Will H. Low, who became The Wrecker’s protagonist, artistic poseur Loudon Dodd. Stevenson’s good friend Charles Baxter took offence when he recognised himself as the hard-drinking “hero” of The Wrong Box, Michael Finsbury. But it was of James Durie, the charismatic villain of The Master of Ballantrae, that Stevenson wrote “for the Master I had no original, which is perhaps another way of confessing that the original was no other than myself” (227).[ii]

About the Author

Audrey Murfin is Associate Professor of English at Sam Houston State University and the author of Robert Louis Stevenson and the Art of Collaboration.

[i] Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson. Eds. Bradford Booth and Ernest Mehew. Yale UP, 1994-95, volume 8 page 364.

[ii] The Master of Ballantrae: a fragment, draft for a preface, Huntington Library, reprinted in The Master of Ballantrae, ed. Adrian Poole, Penguin, 1996, p. 227.