Barton Palmer, co-series editor of Traditions in World Cinema and Calhoun Lemon Professor of Literature at Clemson University, interviews Charlie Michael about the latest book to publish in the series: ‘French Blockbusters: Cultural Politics of a Transnational Cinema’.

Palmer: Tell us a bit about your book.

Michael: The title is actually meant as a gentle provocation. I want the combination of “French” and “blockbuster” to spur as many questions as it does answers. After all, French cinema isn’t usually associated with the type of digitized spectacle that we see in recent big budget, franchise event films like Avengers: Endgame. If anything, most French auteurs are better known at home and abroad for their playful rejection or artful re-appropriation of Hollywood’s methods. Right?

Anticipating that my title itself would raise related questions about economies of scale and cultural power, I organized this book as a series of measured responses and caveats. Over the past thirty years, the French industry has been both fascinated and repulsed by the possibility of producing its “own” blockbuster cinema to play Hollywood’s high stakes game. Since the 1980s in particular, government officials, trade lobbyists and producers have pushed an agenda to find new resources to support a class of aggressive, commercial French films that are more appealing to audiences with a taste for global popular culture. Thirty-some years later, we can say that those efforts have largely succeeded. An assortment of popular films like Amélie (Jeunet 2001), Les Choristes (Barratier 2005), Bienvenue Chez les Ch’tis (Boon 2008) and Intouchables (Tolédano & Nakache 2011) have broken records, and there are now even numerous viable French franchises like Taxi and Astérix. France is now populated with multiplexes and large distribution chains that pack weekend marquees with star-driven genre films. At the same time, while a handful of variously “big” productions tend to drive box office returns almost every single year, they also usually face predictable rebuffs and backhanded compliments from critics – “too commercial”, “too formulaic”, “too American.”

France is a country that cares deeply about the quality of its cinematic output. It seems like every time a new French-made film succeeds on a grand scale these days, it provokes a new variation on what has become something like an ongoing public debate about the status of film art in the age of accelerated capitalism. Can an overtly commercialized cinema ever be considered French in any legitimate way? What does the future of this particular national cinema look like if domestic audiences are now most interested in watching lowbrow comedies like Les Tuche (Baroux 2011) and its biggest export success rides on Hollywood replicas like Taken (Morel 2008) and Lucy (Besson 2014)? A smattering of panicked and infuriated responses to such popular hits in the press now seems almost as inevitable as the staid, diplomatic language of CNC reports, which dutifully catalogue the fortunes of each and every film. And yet, I would argue, the sheer amount of nervous energy that continues to percolate around each surprising success story or catastrophic failure – Chapter 4 is about Luc Besson’s Valérian (2017) – also offers an important case study for how France is more generally ‘making sense’ of its own symptoms of cultural globalization.

Palmer: What inspired you to research this area?

Michael: I’ve always loved movies. I’ve also always been interested in France. I’ve studied the language since high school, and worked at a wonderful immersion camp in my late teens (Concordia Language Villages), but my first real experience of the culture was on a study abroad program to Paris during the spring of my junior year in college. I knew almost immediately that it was my favorite city in the world, and it still is. I’ve never been to a place so alive with excitement about cinema. At the same time, I have to admit that my earliest experiences in France were also as an outsider. When I saw French movies as a young person, surrounded by native speakers, I often felt both awestruck and a bit alienated – not as much by the spoken words but by the cinematic technique and general attitude. French movies were just so differently calibrated than the films I dreamed of as a kid – Star Wars or Raiders of the Lost Ark. At the risk of speaking too generally, I have to admit in retrospect that my book comes right out of those encounters in some way. It is a comparative project, one that I think honors the numerous cultural differences between Hollywood and the French film industry, but also offers an alternative perspective on the way they relate to one another – or at least a different one than the versions we usually hear.

The first spark for the actual research for the book came in a brilliant course on Hong Kong cinema that I took at the University of Wisconsin about fifteen years ago with David Bordwell. At that time, there were a number of rather unexpected movies coming from France that featured martial arts action scenes. These were films that looked nothing like the ones I studied in my French film courses. Some had English dialogue and international stars. Kiss of the Dragon (Nahon 2001), for instance, was the very first film produced by EuropaCorp (the company founded by director Luc Besson that plays a crucial role in the book), and it starred Jet Li and Bridget Fonda and – at first glance — basically looked like a typical Hollywood action film. Other films in the cycle were in French but far more overt about their mixed, transnational influences. I was particularly struck at the time by a film called Brotherhood of the Wolf / Le Pacte des loups (Gans 2001), which even now I find to be joyfully difficult to describe. It’s part period adventure and part horror film, with a visual style that splices Italian goth, kung fu and digitized video game effects. Honestly, both films seemed totally crazy coming from France at the time, but they were the type of crazy that compelled me to know more. Since then, action genres in general have experienced something of a renaissance in the Hexagon – something I write about extensively in Chapter 5. I had no idea that my initial curiosity about a few films could launch a journey that would end up being so long – and so fruitful. The book we see today also owes a great deal to my mentor and friend, Kelley Conway, whose confidence in this project never wavered even when mine did.

Palmer: Why have critics in France and elsewhere been slow to come to grips with this aspect of the national cinema?

Michael: This question cuts to the heart of my book’s subtitle, “Cultural Politics of a Transnational Cinema.” The short answer is that the idea of a purely “commercialized” cinema has – almost since the beginning – clashed with how the French film industry and cultural establishment imagine their place in the world of filmmaking. The longer answer is, of course, far more complicated, but I’ll try to offer an abridged version here.

First, in French, the term “cultural politics” (la politique culturelle) refers to a long Gallic tradition of supporting the arts through government means; historians usually trace it back to Louis XIV. The more modern version of this philosophical approach – often termed the ‘cultural exception’ (l’exception culturelle) or, more recently, ‘cultural diversity’ (la diversité culturelle) – derives from a number of different French institutions and policies designed in the 20th century to both stimulate indigenous cultural production and protect it from foreign competition. For the cinema, the key antagonist has perennially been Hollywood, and the crucial period occurs just after World War II, when the CNC (Centre National de la Cinématographie) is created as an independent body that oversees a cinema support fund (compte du soutien) comprised of box office taxes that it reroutes to commercially successful French producers via ‘automatic subsidies’ for their subsequent films (soutiens automatiques). Crucially, in 1959, under the country’s celebrated first Minister of Culture, André Malraux, another program is added to the first – by then deemed too nakedly commercial. Starting that year, there is a second CNC funding pool for ‘selective aid’ (soutien sélectif), meant to support properly ‘cultural’ forms of cinema without a direct connection to box office success. Around the same time, a new designation for art house cinemas (Art et essai) offers economic incentives to domestic theaters that agree to screen more ‘challenging’ forms of filmmaking. These reforms gain a reputation worldwide, largely because they support the young French directors of the 1960s, who turn their low-budget, personal films about Paris into some of the most indelible signatures in film history (Varda, Truffaut, Godard, et al.).

It may sound clichéd – but the rebels of the past have become a measuring stick for legitimate artistic claims of the present. To this day, the artistic legacy of the New Wave and its ‘cultural’ distinctions from market concerns has such a strong, implicit connection to cinematic “Frenchness” that many contemporary directors almost cringe when you mention it. And when the reformers and filmmakers I’m most interested in writing about in the book sought to promote more commercialized filmmaking practices in their home country during the 1980s and 1990s, they had more to worry about than just the immense popularity of Hollywood. They also had to contend with the ideological strength of their own cinematic heritage, which is steeped in a celebrated history of ideas about what a “healthy” relationship between art and commerce should look like. It’s actually kind of hard to overstate how much influence this general kind of thinking – what I call an “exceptionalist” discourse – still has today.

And this is how we get to the second part of my title. Transnational cinema is quite a popular theoretical concept these days – at least for academics. As a field, it is really still at the beginning, and has been construed to mean different things, but I think scholars agree that transnational film scholarship should be devoted to scrutinizing how “new” film and media practices call for different approaches to how we make sense of films and their history. Invariably, this involves grappling with the inertia of national “containers” as a convenient but somewhat inescapable influence on our thinking. You might be surprised that the “of” and the “a” are actually the two words I stewed about most (why not simply use “and”?). Yet given the expansive possibilities of the word, it became clear to me that one book cannot possibly account for the myriad ways that contemporary French filmmaking might be considered transnational. Rather, I have written a book about the overlooked history and polarizing consequences of a particular form of transnationalism that has recently taken hold in the industry – one that Mette Hjort has called “globalizing transnationalism.” So as I mentioned earlier, what I call the “French blockbuster” phenomenon is less typified by any one set of generic patterns or stylistic features than it is by a shared history of reform efforts and by a vigorous set of polemics it continues to generate across film culture.

Palmer: Did you get exclusive access to any new or hard-to-find sources, including industry records? Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

Michael: I do think my research trail was pretty unconventional – even if most of the resources I used were publicly available. I found lots of research materials in different nooks and crannies of Parisian bookstores and memorabilia shops, but most of my nitty gritty archival work took place in two venues – the document resource room in the basement of the CNC and the periodical stacks at the BiFi (Bibliothèque du Film) at the Cinémathèque.

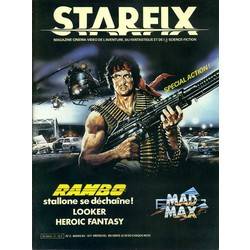

The French film industry is amazingly prolific at keeping track of the facts and figures about everything it does. Thanks to the wonderful archivists at the CNC, I was able to peruse numerous statistical manuals, but also to locate literally dozens of carefully compiled thematic dossiers through a database. These usually combined news reports from the trade press with documents from the Ministry of Culture and various other government sources. In the early stages of my work, reading widely among them helped me to formulate a knowledge base that later became my Introduction and Chapter 1. When I sought more material specifically about the films I was interested in, the librarians at the BiFi were wonderfully accommodating – but also shocked about what I was looking for. Sometimes it felt like I was the very first person – and definitely the first American – to ask for certain materials. I know I’m not the first visitor to peruse back issues of 1980s popular culture magazines like Starfix, Mad Movies and Ecran Fantastique, but I think it is safe to say that those pages get far less mileage than those of the Cahiers du cinéma and Positif issues residing just a few alphabetized aisles away. I really encourage others to take the plunge I did – they are full of information and their glossy pictures make them quite entertaining to read.

During my trips to Paris over the past decade, I also managed to conduct a number of interviews with industry professionals. In every case I was greeted graciously, and the discussion went on far longer than planned. I would always learn new insights in those exchanges, and it was refreshing to meet people who not only cared about my topic, but also had actually met the people or experienced the events that I describe in the book. These perspectives allowed me to test my broader hypotheses, as well as to solidify the distinctions between the three common transnational “framing narratives” I propose in Chapter 2.

Palmer: Would you like to see the French cinema considered more broadly in all its aspects, including production series that are more commercial than artistic?

Michael: Absolutely. My hope is that this book will help shed some light on a whole category of recent popular filmmaking that is too often glossed over – certainly abroad, but also within France. Ideally, this book will not only excavate an alternative history, but also inspire readers to reflect on how their preconceptions about French cinema invariably become a self-fulfilling prophecy – affecting their ideas about what a national industry has been in the past, what it is now and what it can be in the future. I am certainly not alone in this sort of reclamation project; over the past few decades, quite a few scholars have worked hard to highlight the popular cinematic traditions of France. In that respect, this book exists only because of the groundbreaking work of many others before me.

Palmer: What’s next for you?

Michael: I’m currently enjoying the completion stage of this book – and searching for new ideas. I do have one project already lined up with Edinburgh UP – a co-edited, revisionist volume of auteur studies tentatively entitled The Other French New Wave. My two ambitious colleagues and I are actually planning two tomes, one that reconsiders a list of forgotten French directors from the 1960s and 1970s, and a second that sheds light on the numerous younger directors who reinvented its legacy from the 1980s to the 2000s. I’ve also got a couple of self-authored projects in store. One of them grew from material I just couldn’t fit into French Blockbusters. Broadly speaking, the book – which I’m calling Digital Hexagon – looks at how recent government regulations in France have literally tried to shape how individual citizens consume online culture – primarily via strict regulations regarding file sharing and streaming content. In another book, I’d like to document the growing involvement of the Sri Lankan Tamil community in French cinema and in the European media industries more broadly. Most of them arrived in Europe in the 1980s or 1990s and are just beginning to gain media representation. In France, the best-known instance of this is Dheepan (Audiard 2015), but there have been many other Sri Lankan actors involved in French films of late, often playing small but memorable roles. La Fémis, the national film school, also just graduated its first Sri Lankan Tamil director last year, so I suspect there will soon be more titles to add to my filmography. Honestly, after pursuing one end of the production spectrum for so long, I’m really excited to look at contemporary French filmmaking from an entirely different angle.

- French Blockbusters: Cultural Politics of a Transnational Cinema is available now in the Traditions in World Cinema series. Find out more on the Edinburgh University Press website

Charlie Michael earned his PhD in Film Studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and currently teaches Cinema and Media Studies courses at Emory University in Atlanta. He co-edited the Directory of World Cinema: France (Intellect, 2013) and his work has also appeared in SubStance, The Velvet Light Trap, Quebec Studies, French Politics, Culture & Society, and A Companion to Contemporary French Cinema.