As the Mueller investigation comes to a close, our attention shifts to a more familiar fight: the one between Congress and the White House. The Democrats’ control of the House has handed them institutional power to use Congress’s oversight mechanisms against the White House. President Trump, however, is not interested in cooperating. As House Oversight and Reform Committee Chair Elijah Cummings recently wrote in The Washington Post: ‘The White House has not turned over a single piece of paper to our committee or made a single official available for testimony during the 116th Congress.’

The executive and legislative branches have been playing the checks-and-balances game on power for decades. But, in the modern era, it becomes difficult to understand the Trump administration’s actions without examining its historical roots.

Information Wars: Presidential Control vs Congressional Access

Many will immediately compare Trump’s behaviour to that of President Richard Nixon. I argue that we should look back further, to Nixon’s mentor: President Dwight Eisenhower. The Vesting Clause of the Constitution has allowed for the expansion of president power since the Washington administration. But it was the dramatic changes under Eisenhower that set the precedent for executive privilege.

In the immediate post-war period, the rise of Communism and the Cold War presented external and internal threats. President Truman responded to the communist threat at home through unilateral actions. These included Executive Order 9835, which instituted an employee loyalty program within the executive branch. Soviet threats and the Korean War, coupled with consistent actions from the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the rise of McCarthyism, altered the president’s thinking. The president had learned the need to be cautious and careful in the control of information, even to Congress. This new Cold War Paradigm mindset solidified within the executive branch.

Truman and Congress worked in lockstep through most of this period. Congress responded to Truman’s anti-communist fervency in kind, demonstrating that this new Cold War Paradigm had become a learned response. However, a rift emerged during the debate over the Internal Security Act of 1950, known as the McCarran Act. The bill mandated the White House to publicly disclose information on multiple Cold War programs. Truman vehemently opposed those provisions and vetoed the legislation. Congress argued that they needed greater oversight on these anti-communist measures. They opted to override Truman’s veto. The split between the president and Congress, grounded in the Cold War mindset, established a growing divide over access to information. The president sought greater control; Congress wanted greater access.

Eisenhower: A Growing Divide

This divide grew under Eisenhower. Upon coming into office, Eisenhower immediately sought to move deeper into the Cold War Paradigm mindset with Executive Order 10450. This order institutionalised security requirements for government employment. It allowed Eisenhower to fire nearly 3000 federal employees. He claimed that they failed to meet the new requirements and were a threat to national security.

The firings caught the attention of a freshman House member from California named John Moss, who served on the House Post Office and Civil Service Committee. Moss requested the personnel files for every official that Eisenhower fired. He was flatly denied, with the White House claiming national security concerns. As a freshman Democratic member in a Republican-controlled House, Moss had no real power to respond.

Setting the Precedent of Executive Privilege

Eisenhower’s control over information was institutionalised in 1954 with two actions. The first was the creation of the Office of Strategic Information (OSI) within the Commerce Department to oversee all public access to government information. OSI quickly cut off the flow of executive branch information to Congress and the press.

The second and more prolific action came on May 17, 1954. Eisenhower sent a letter to Defense Secretary Charles Wilson. Eisenhower told Wilson to withhold information and testimony from the Senate Government Operations Committee for an upcoming hearing, known now as the Army-McCarthy Hearings. Eisenhower’s letter included a memo from Attorney General Herbert Brownell that established an inherent constitutional privilege for the president. This allowed for the denial of any information to Congress in the public interest and for national security reasons. This memo created and established the precedent of executive privilege.

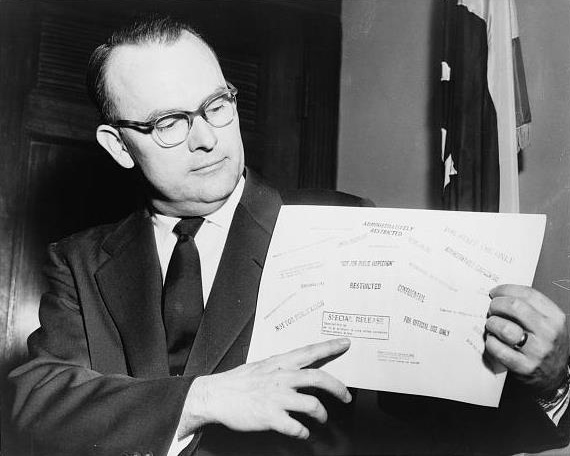

Congress’ Response: John Moss and FOIA

Eisenhower’s claim of this new inherent constitutional authority was not questioned by the Republican controlled Congress or the public. Both had grown weary of Senator McCarthy’s fearmongering. Then, the 1954 midterm elections gave control of Congress back to the Democrats. In spring 1955, the House created the Special Subcommittee on Government Information, with one John Moss serving as its chair. The Moss Subcommittee – as it became known – was given broad jurisdiction and was specifically tasked with oversight of all executive branch information policies. The creation of the Moss Subcommittee would institutionalise the issue of government secrecy and executive privilege in Congress. It was instrumental in setting up a 12-year battle that would result in the creation of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) as a direct congressional check on presidential power.

Trump and Executive Privilege – What Next?

Though it has been more than 50 years since FOIA was implemented and almost as long since the Supreme Court legitimised executive privilege as a constitutional power in the United States v. Nixon decision, these issues continue to play out in contemporary politics. The Trump administration is not unique in denying information and testimony to Congress: it is following a precedent established decades ago.

But Trump would be unwise to assume Congress will be complacent, especially with the Democrats back in control of the House. With history as a lesson, executive privilege will only go so far before eliciting a legislative response. It was a Democratic-controlled Congress that was able to finally thrust FOIA on President Lyndon Johnson in 1966, after all. And it got Johnson’s signature on the bill – even though he was adamantly opposed to the legislation.

By Kevin M. Baron

Kevin M. Baron is Lecturer and Civic Engagement Coordinator for the Bob Graham Center and the Department of Political Science at the University of Florida. Kevin’s research focuses on Congress and the Presidency, paying particular attention to the politics of policymaking. His book Presidential Privilege and the Freedom of Information Act examines how the Cold War created a paradigm shift in thinking over public access to government information that became entrenched within the executive branch.

Find out more about Presidential Privilege and the Freedom of Information Act by Kevin M. Baron

Find out more:

- Executive Order 9835

- Executive Order 10450

- Eisenhower’s letter to Defense Secretary Charles Wilson

- Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

- United States v. Nixon decision

Image credits

- ‘Trump and Members of Congress discuss Infrastructure; February 2018‘. Public Domain. Via Wikimedia Commons.

- ‘Welch-McCarthy-Hearings‘. Public Domain. Via Wikimedia Commons.

- ‘Eisenhower d-day‘. Public Domain. Via Wikimedia Commons.

- ‘Moss‘. Image provided by the author.

- ‘NSC meeting 15 09 1966‘. Public Domain. Via Wikimedia Commons.