In 1998, the celebrated lesbian film scholar B. Ruby Rich wrote:

‘I don’t want to make the mistake of falling into that comfortable old victim box, complaining of absence in the midst of presence. We’re not invisible anymore’ (58).

In 1999, Patricia White observed that lesbianism was by now ‘an intelligible social identity, visible on the nation’s television and movie screens’ (6). And Julianne Pidduck signalled in 2003 the ‘“hypervisibility” of lesbian/gay/queer works’ in North America (266). Two decades ago, then, it became possible to suggest that the lesbian had reached the realm of the visible.

For several years now, we can consider ourselves to be spoilt for choice when it comes to scouting for lesbian films in the London Film Festival programme (though it’s all relative, of course). Lesbians on-screen in the 2018–19 season cross genres, tastes, moods, periods and audiences, including in Disobedience (Lelio, 2017), Vita and Virginia (Button, 2018) and The Miseducation of Cameron Post (Akhavan, 2018). We begin to see popular culture mainstreaming lesbianism in a way that might not have been imaginable even at the turn of the century.

The same decades that have heralded remarkable transformations in the inclusion of lesbianism in mainstream political, social and cultural fields have also witnessed a revolution in the academic study of sexuality, which has veered away from the labels associated with the identity politics of 1970s and 1980s liberation movements. Critical discourses have increasingly replaced identity categories such as lesbian with the more fluid notions of queer sexuality. Situated against this context, Lesbian Cinema after Queer Theory takes as its starting point three interlinking observations: firstly, that lesbianism is more visible on-screen now than it has ever been; secondly, that even so, the discussion of the lesbian’s screen presence is beset by comparisons to older models of representation; and, thirdly, that queer theory has forcefully ignited the discussion of sexuality over the past three decades but has concurrently diminished the perceived relevance of lesbianism as a term of engagement.

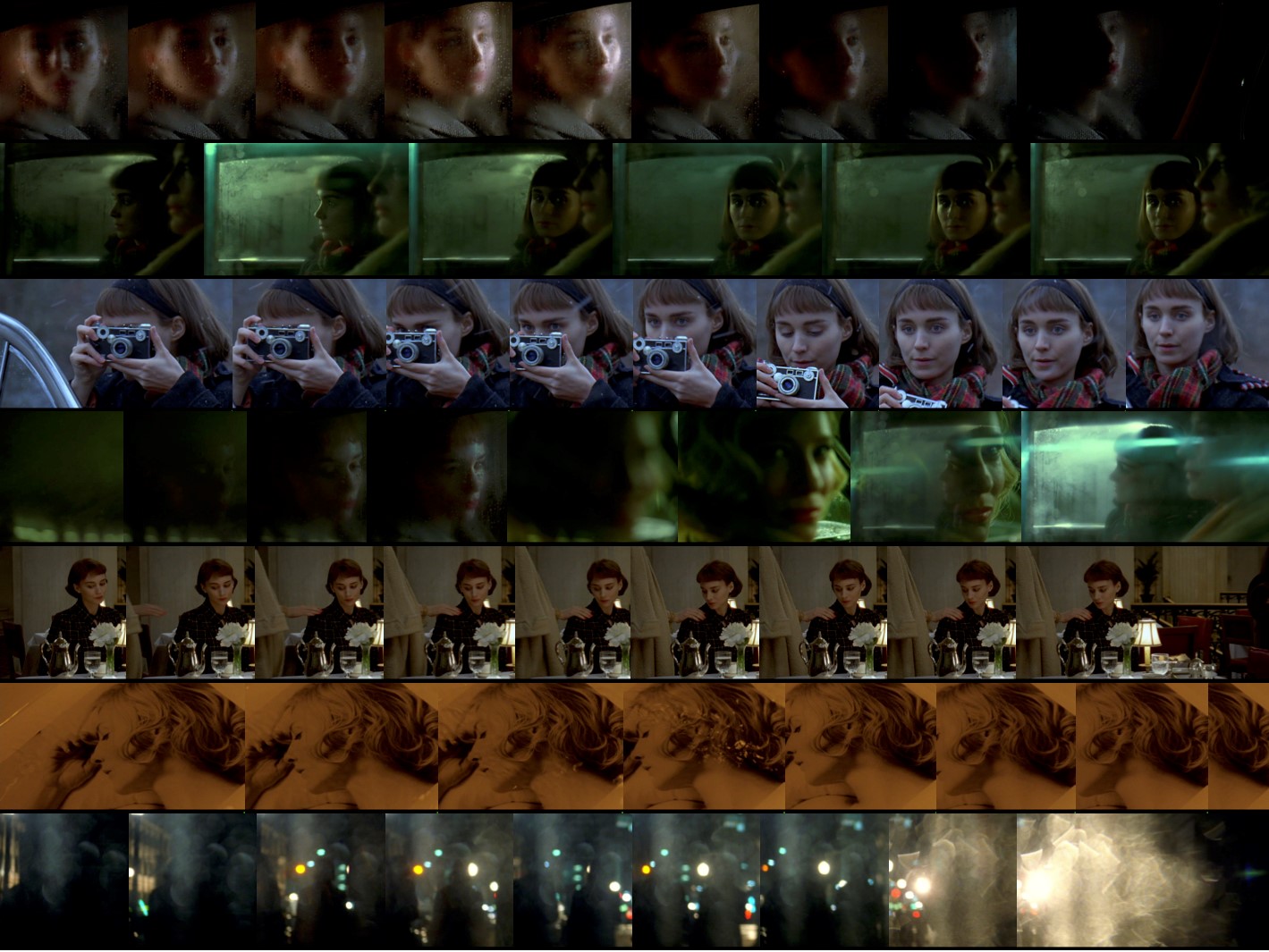

Instead of being chosen solely on the basis of their contribution to the visibility effect (for instance, breadth of distribution or garnering of mainstream awards), the films discussed in this book bring to the fore the paradoxical nature of this so-called visibility. Throughout, I identify and theorise the kinds of cinematic language through which the figure of the lesbian has continued to be made legible on the screen. In doing so, I argue that, rather than providing another identity category, queer is the charge or potential through which lesbianism is enabled to expand its borders.

Rather than advancing a conventional history of the recent past of lesbian representation, then, or an overview of the films that have made the lesbian visible, in Lesbian Cinema after Queer Theory I analyse a series of films released in the past two decades alongside the invigorating theories of sexuality that problematise their legibility as lesbian. I offer close readings of key contemporary films such as Blue Is the Warmest Colour (Kechiche, 2013), Water Lilies (Sciamma, 2007) and Carol (Haynes, 2015) alongside a broader filmography encompassing over three hundred films released between 1927 and 2018.

These films are united by an emphasis on the diegetic role of spectatorship and voyeurism in the construction of desire. They all include scenes of what I think of as intensified spectatorship, revealing the ways in which the cinematic apparatus links desire to the image. Central to the book’s aim is the reconsideration, through queer theory, of theoretical arguments about the tensions between identification and desire. These lie at the very heart of debates over what constitutes lesbianism in the visual field. Lesbian Cinema after Queer Theory negotiates these theoretical tensions in order to mark out the ways in which we might simultaneously trouble and sustain lesbian cinema in the era of the visible.

Clara Bradbury-Rance works in the Department of Liberal Arts at King’s College London, where both her teaching and research focus on feminist and queer theories of film, popular culture and new media. This post is excerpted and adapted from her book Lesbian Cinema after Queer Theory, which is published by EUP in March 2019.

Sources

- Dyer, Richard and Julianne Pidduck (2003 [1990]), Now You See It: Studies in Lesbian and Gay Film, 2nd edn, London: Routledge

- Rich, B. Ruby (2013), New Queer Cinema: The Director’s Cut, Durham, NC: Duke University Press

- White, Patricia (1999), Uninvited: Classical Hollywood Cinema and Lesbian Representability, Bloomington: Indiana University Press