Tell us a bit about The Pilgrims Society and Public Diplomacy, 1895–1945

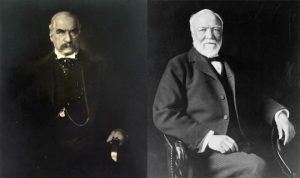

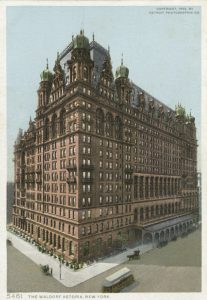

My book is about the Pilgrims Society, which is an elite dining club that was founded in London in 1902 and in New York in 1903. Not many people today will have heard about the Society but it was high profile in its early days and newspapers often reported on the speeches made at its meetings and events. My argument is that the Pilgrims used its high profile to promote its ideas about Anglo-American friendship. It had many famous members, including J.P. Morgan and Andrew Carnegie, and it held banquets in exclusive restaurants and hotels (like New York’s Waldorf Astoria) for powerful politicians and ambassadors. It acted as a transatlantic network for government figures, diplomats, businessmen, and senior journalists and, as a result, contributed to the development of what we now know as public diplomacy. The book covers the period before the UK–US relationship was called the ‘special relationship.’ Though the relationship was improving in the 1900s, the Pilgrims had to work to promote Anglo-American friendship during and after the First World War, when a number of disagreements caused diplomatic tension between the two countries.

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

The Pilgrims Society has sometimes been at the centre of conspiracy theories about secret societies that run the world. These theories of course don’t stand up to scrutiny. The Pilgrims has never run the world and it isn’t really secret. Even so, it is elitist and exclusive and it has sought to influence how the public in both Britain and the United States have thought about Anglo-American relations. This is why I argue that the Pilgrims Society conducted public diplomacy. A good comparison between the Society’s real activities and some of the more outlandish theories comes from the 1920s, when the anti-British mayor of Chicago was worried about allegedly pro-British history textbooks influencing American schoolchildren. There was a campaign to address this influence and the Pilgrims was accused of being involved in seeking to undermine American independence. The irony was, however, that while the Pilgrims Society wasn’t really doing what the mayor and others had accused it of doing, it had nonetheless played something of a semi-official propaganda role during and after the First World War.

Did you get exclusive access to any new or hard-to-find sources?

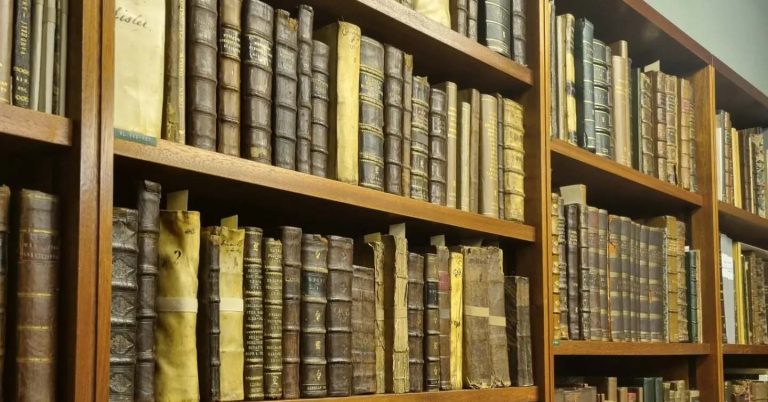

Most of the material I used for the book is from archival collections that are open to the public. The exception to that, however, was the material belonging to the New York branch of the Society, which is held privately. I was able to visit the Society’s offices in an old office block off Sixth Avenue and spent time going through their boxes of papers. This included minute books and correspondence, all of which was unsorted and uncatalogued.

Did your research change your perceptions about the world?

The findings of my research are a reminder that political and diplomatic events often happen under the radar. I was interested in looking at how the Pilgrims influenced official Anglo-American diplomacy, but the Society is rarely mentioned in official sources. Instead I had to work out what happened from newspaper sources, the Pilgrims’ own material, and also from private correspondence. Doing this helped show that a group few people have heard of today provided a network and an outlet for influential individuals seeking to promote Anglo-American friendship. I don’t argue that the Society set the agenda for official relations but it was certainly involved in many of the main diplomatic developments between the two countries, during the first half of the twentieth century at any rate.

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

The most exciting thing about doing the research for this book was the chance to visit archives in cities I’d never been to before, including Cambridge (Massachusetts) and Washington D.C. My favourite archive was, and probably still is, New York Public Library. The main building is really striking and very beautiful but it doesn’t feel stuffy or anything like that. It’s the city’s public library which means that a whole variety of people go in to use it, not just academic researchers. It’s also where they filmed part of the original Ghostbusters film, which I’ve always loved, so it was exciting to go there for that reason too! They also filmed part of Ghostbusters at Columbia University, which I visited too.

Did your research take you to any unexpected places or unusual situations?

One unexpected situation was to discover that I was on the same flight from London to New York as Billy Connolly. I saw him get off and on the plane, and stood next to him waiting to reclaim our luggage at JFK airport.

By Stephen Bowman

Stephen Bowman is Lecturer in the Centre for History at the University of the Highlands and Islands. He holds degrees from Northumbria University and the University of Stirling. His current and future research centres on transatlantic ideological exchange, with a particular focus on the Scottish-American connection. Stephen is a past winner of the Transatlantic Studies Association’s prestigious Donald Cameron Watt Prize. He has taught at the University of Stirling, Durham University, Newcastle University and Northumbria University.

The Pilgrims Society and Public Diplomacy, 1895–1945

Stephen Bowman

Part of the

Edinburgh Studies in Anglo-American Relations series

Published March 2018

Find out more…

Image credits:

- New Year’s Eve Dinner at the Savoy in 1906: Max Cowper, 1907.

- J.P. Morgan: Edward Jean Steichen, 1903

- Andrew Carnegie: Theodore C. Marceau, 1913

- NYC Public Library Research Room: photograph by Diliff, edited by Vassil, CC-BY-SA-3.0