In James Benning’s film Concord Woods (2014), we watch a replica of Henry David Thoreau’s famous cabin at Walden Pond. The cabin is first shown during the summer solstice, graced by the golden sunlight. The shot lingers for sixty minutes while the sun gently sets. Next, we see the same cabin during the winter solstice, from time to time under gently falling snowflakes. Again, the shot lasts for sixty minutes, but this time the daylight does not give way to darkness. During the first shot, Benning’s voice reads from Thoreau’s ‘A Plea for John Brown’ (1859), an abolitionist who led an insurrection against slavery and was later hanged for his violent act of civil disobedience. Over the next frame, he reads from Economy (1847-1854), the opening section to the same author’s Walden.

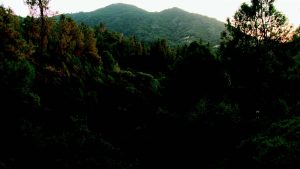

Concord Woods points back to the equally picturesque cabin in Benning’s Stemple Pass (2012). This film begins in spring, where the cabin almost disappears in the lush green forests of the Sierra Nevada. The image becomes more disturbing once Benning’s voice begins to recite tales of survival, freshly killed animals and gum infections. In this case, the words that Benning is reading come from the journal of Ted Kaczynski, better known as the Unabomber, and for a while America’s most feared terrorist. Through these two lovers of nature, one worshipped, one reviled, the landscape is presented as the locus of various forms of violence. In so doing, the constellation of cabin projects (which includes other film works and installations too) subtly explodes the stories we tell about each other, our environments and our actions.

Originally trained in mathematics and converted to art by a chance encounter with John Cage at the University of Wisconsin, James Benning has been making films since the early 1970s. Over the years, Benning has developed a highly original language, which, together with his privilege for uncommon landscapes, makes him a unique filmmaker in contemporary film culture. Benning’s language is marked by durational static shots and natural sound. At times, duration takes over and, in BNSF (2013) and Nightfall (2012) for example, the film is simply one single extended shot (BNSF lasts for 3 hours and 13 minutes). Even in those films that do not push duration to such extremes, Benning creates exacting, compositionally rigorous frames that leave the audience to confront the choreography of the world. The director has described his films as ‘found paintings’: not only do they offer striking pictorial qualities, but they also toy with the idea of returning the moving image to its original stillness.

The films also offer a systematic investigation of the relations between man, landscape, and the filmic medium. During the last decades, it has become increasingly clear how much these investigations have to offer key contemporary debates about ecology, the age of the Anthropocene and the development of digital technologies. Benning stands today as an important precursor to the non-pastoral attitude to the environment required by the Anthropocene. In Benning’s films, what we could once call the ‘natural environment’ is a complex, ambiguous, politically charged field, which is always simultaneously entangled with the human and technology, and capable of resisting and reversing human designs.

As the opening examples demonstrated, rather than being conciliatory and aesthetically appeasing, Benning’s films are – whether subtly or explicitly – often concerned with the murderous, the destructive and the ruinous. The entire California trilogy, for instance, (El Valley Centro (1999), LOS (2000), SOGOBI (2001)) is an investigation of the many consequences of water politics in southern California. Over the six hours of the trilogy, agro-industrial processes are observed in relation to the intense desertification they cause. Whether he is reminding us that unequal access to resources is one of the main sources of war or showing nature as the locus of social antagonism – from civil disobedience to terrorism – Benning keep us waiting just long enough to see how much violence is stored in our landscapes.

Nikolaj Lübecker is Professor of French and Film Studies at St John’s College, University of Oxford.

Daniele Rugo is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Arts & Humanities at Brunel University, London.

Related links: