Western Europe experienced the immigration of people from a Muslim background after World War II who settled in countries like France, Britain or Germany to fill the labour shortage and made important contributions to the economic recovery of Western European countries in the post-war period. There are now well-established Muslim presences across Western Europe which include the children and grand-children of early Muslim immigrants. Countries like Britain, France and Germany have received the bulk of Muslim immigration and have now the largest Muslim populations in Western Europe. Both public and academic discourse around Muslims in Europe is very often shaped by the particular experiences of Muslim immigration and settlement in these larger Western European countries and revolve around the specific postcolonial relations of former European colonial powers to the countries of origin of Muslim immigrants, the continuous socio-economic marginalisation of Muslims in these countries, issues around the integration of Muslims and fears around radicalisation and violent extremism. Within this discursive framework the experiences of smaller European countries located in the geographical periphery of Europe are usually overlooked. Ireland is one of those countries of whose Muslim population little has been known until recently.

The experience of Muslim immigration and settlement to the Republic of Ireland after World War II is a different story. Muslims began to form a permanent communal presence in Ireland from the 1950s onwards. The majority of them came as students from privileged backgrounds, to study in the medical field at Irish universities in particular. Those who stayed in Ireland worked as professionals and doctors and became part of the Irish middle- and upper-class, reflecting their successful socio-economic integration into Irish society. In this sense, Muslim immigration and settlement to the Republic of Ireland was more akin to the US experience.

With the arrival of the Celtic Tiger on Irish shores, Ireland’s years of rapid economic growth from 1995 to 2008, came mass immigration. While Ireland was a fairly homogenous society before the Celtic Tiger years, it has been transformed into one of the most globalised and culturally and religiously diverse societies in Western Europe. The Muslim population grew rapidly, from around 4,000 in the early 1990s to current estimates of about 65,000. With mass immigration, the socio-economic profile of the Muslim population has also changed. The Muslim population has transformed from a small middle-class community to a population that is marked by social disparity between the more established migrants and the newcomers who have come as labourers, asylum seekers and refugees during the Celtic Tiger years. While the socio-economic profile of the Muslim population in Ireland has become more mixed, there is still a strong middle-class component within the Muslim population of Ireland.

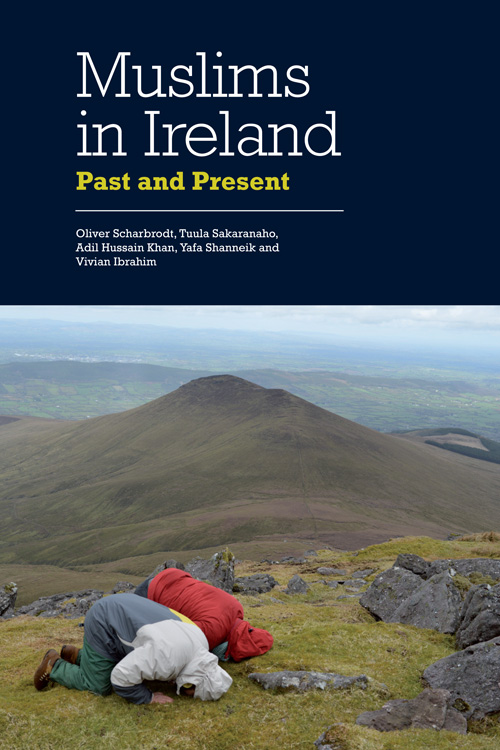

The history of Muslim immigration is different to that of larger Western European countries. Muslims moved into a society that was and still is one of the most religious in Europe. Catholicism has historically played an important role in defining Irish national identity. Although many Irish Catholics have turned away from the Catholic Church in the last 20 years, church attendance is still relatively high compared to the rest of Europe. Religion has always played an important public role in Irish society, though this has been contested for some time now. The public expression of one’s religion is therefore not seen that much of a scandal as in the more secular societies of Western Europe. Official representatives of Muslim organisations in Ireland often praise the Irish “respect for religion”, saying that the religious ethos of Irish society makes it easier for Muslims to find understanding for their particular religious needs.

One good example of this are the two state-funded Muslim primary schools in Dublin. The establishment of Muslim faith-based schools is hugely controversial in Western Europe. Fears around further ghettoization and limited if not non-existent encounter of pupils with “European values” are often cited against the establishment of such schools. The establishment of Muslim schools in Ireland was swift, unproblematic and without any controversy. When a Muslim organisation approached the Irish Department of Education to request permission to establish a state-funded Muslim school, only small bureaucratic hurdles had to be overcome, and the first school was opened in 1990. Given the high demand, a second school was opened in September 2001, a few days after 9/11, without any notice by the Irish public. The fairly easy and uncontroversial establishment of two Muslim primary schools results from the particular denominational nature of the Irish educational system which worked in favour of Muslims who wanted their children to be taught at an Islamic school. Primary and secondary education is traditionally the domain of the churches in Ireland, the Catholic Church in particular, with almost 90% of primary schools run by the Catholic Church. As Protestants and Jews, Ireland’s historical religious minorities, run their own schools, it was only logical that Muslims, as a newly arrived religious minority, should have their own schools as well.

However, the Catholic ethos of Irish society is a double-edged sword. The Catholic dominance in public life and the Catholic underpinnings of Irish national identity exclude people in Ireland, whether Irish citizens or immigrants, who are not Catholic. They are seen as not being properly Irish. This has been the case with the historical religious minorities in Ireland, Protestants and Jews, and is also true for recently arrived faith communities that are primarily constituted of immigrants. Similar discourses of exclusion are encountered by Irish converts to Islam. Very often, they are accused by their families and friends to be traitors to the Irish nation, because they have embraced another religion. The unproblematic establishment of two state-funded Muslim schools suggests a more accommodating Irish context for the needs of Muslims. However, there are only two schools in Dublin, and the vast majority of Muslim pupils have to attend Catholic schools whose religious ethos is informed by Catholicism and where they and other non-Catholic pupils are often coerced to participate in religious activities contrary to their own beliefs.

Ireland provides a different narrative of Europe’s new Islamic presence. On the one hand, there are examples of successful integration: the strong middle-class component in the Muslim population has meant that Muslims in Ireland suffered from a lesser degree of socio-economic marginalisation than their coreligionists in other Western European countries; Ireland’s religious ethos has also created a more accommodating environment for the articulation of religious beliefs in the public sphere than the more secular contexts of other Western European societies. On the other hand, a “hate letter” campaign in 2013 with threatening letters sent to mosques, Islamic organisations and individual Muslims and increasing incidents of racist and Islamophobic attacks show that Ireland is not immune to Islamophobia either. The burgeoning European anti-immigration discourse coupled with Islamophobia, fears of jihadi fighters going to or returning from the Middle East and the increasing securitisation of Islam across Europe have also reached Irish shores.

About the author

Oliver Scharbrodt is Professor of Islamic Studies at the University of Chester, UK, and Director of the Chester Centre for Islamic Studies. He is co-author of Muslims in Ireland: Past and Present (together with Tuula Sakaranaho, Adil Hussain Khan, Yafa Shanneik and Vivian Ibrahim). He is also the editor-in-chief of the Yearbook of Muslims in Europe.