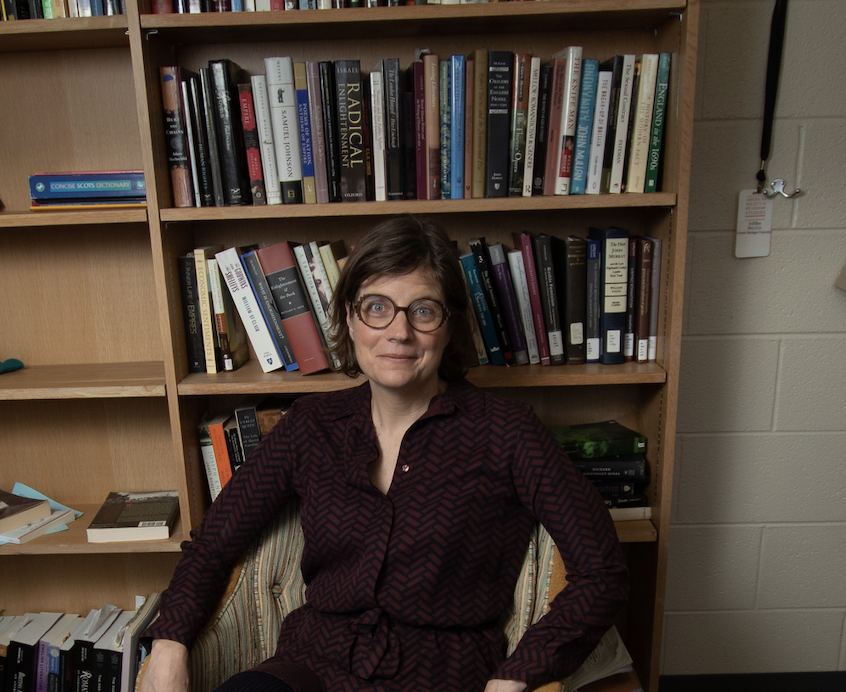

By JoEllen DeLucia

JoEllen DeLucia is the author of ‘Frances Wright’s A Few Days in Athens: Feminst History, Epicureanism, and the Scottish Enlightenment‘ in issue 23.3 of the Journal of Scottish Philosophy.

Tell us a bit about your article.

My article explores Frances Wright’s defense of Epicurus in her A Few Days in Athens (1822). Epicurus was an ancient Athenian philosopher and a materialist, who argued for the senses and pleasure as the best gauges of virtue. Controversially, he also welcomed women as well as enslaved people to his school. Through her work on Epicurus, Frances Wright developed her own understanding of the relationship between pleasure and virtue, and this served as the basis for her feminist philosophy.

Despite its popularly in the nineteenth century, A Few Days in Athens has been hard to place in feminist philosophy and history. It’s generically uncertain; in places, it reads like a philosophical dialogue, but it also borrows tropes from the novel. In addition, pleasure remains difficult to discuss within feminism because of its association with sex and the body. My article grapples with Wright’s attempt to make pleasure central to living a virtuous life.

What inspired you to research this area?

Wright offers me a chance to extend my previous work on Scottish Enlightenment thought and women’s writing in new directions. Wright was a controversial nineteenth-century writer and reformer. She published A Few Days in Athens in 1822, but it was written years before while she was living with her uncle James Mylne, who was Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow. He lectured on Epicurus and likely introduced her to Scottish Enlightenment debates about the value of Epicurean thought in the work of David Hume, Thomas Brown and Thomas Reid. Wright took these ideas with her when she moved to the U.S. and tackled big issues, including women’s rights, labour rights and slavery.

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

I’ve always been passionate about feminist recovery. By this, I mean finding people in the past who were concerned with women’s education, rights and reproductive freedom—well before the label feminism was given to these investments in the late nineteenth century. Wright engages in this same recovery work in A Few Days in Athens. Within the dialogue, Epicurus’s best student and most able advocate is a woman philosopher named Leontium. Through Pierre Bayle’s Historical and Critical Dictionary (1709), I was able to track the historical Leontium, who appears in Cicero and other ancient sources. Wright’s excitement in recovering Leontium echoes my own feelings in bringing Wright back to the attention of today’s readers.

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

I was surprised to find so much discussion of Epicurus within Scottish Enlightenment philosophy. Few Scottish literati went as far as Wright in their embrace of Epicureanism and many were very, very critical, but it was still interesting to see them using Epicurus to refine their own ideas about self-interest, pleasure and even the value of empiricism.

Did you get exclusive access to any new or hard-to-find sources?

I spent a few days in the University of Glasgow’s special collections examining student notes on James Mylne’s lectures and a catalogue of his library. I learned that Mylne began his course on moral philosophy with a discussion of Epicurus. I hope to return and discover more.

Has your research in this area changed the way you see the world today?

In the West, we are often taught to value self-denial and sacrifice—more Stoic virtues. Even the intellectual pleasures Wright defended, such as reading poetry or painting, are often viewed as unproductive, extra and inessential; often, they are framed as feminine pursuits. Wright has helped me think in new ways about the value of pleasure not only in feminist history but also in Western culture more generally.

What’s next for you?

I’ve been working with Wright’s View on Society and Manners in America (1821), which was also shaped by Wright’s experience of the Scottish Enlightenment. In this work, Wright adapts Scottish stadial history, which used economic and political development to gauge social progress. She applies stadial history to indigenous people and enslaved Africans in the U.S. to position them as less advanced than white settlers. Despite her public opposition to the slave trade, you can see her racist assumptions about development undermining her own arguments for equality. Notably, she applied these ideas to Nashoba, the disastrous and failed utopian community that she founded in Tennessee. I plan to use Wright’s Views on Society and Manners in America to examine the history of white feminism in the U.S. and its relationship to Scottish Enlightenment frameworks such as stadial history. Wright was so prolific that I would also like to trace the influence of Scottish philosophy on her later work, potentially culminating in a book-length project.

About the author

JoEllen DeLucia teaches literature, writing, and gender studies at Central Michigan University. She has written a book A Feminine Enlightenment: British Women Writers and the Philosophy of Progress, 1759-1820, edited a collection of essays with Juliet Shields entitledMigration and Modernities: the State of Being Stateless, 1750-1850, and is soon to publish a multi-volume edited collection of Gothic novels, chapbooks, magazine fiction, and plays from the long nineteenth century with Jennifer Camden. She has also authored several articles in journals and essay collections on eighteenth-century women’s writing, moral philosophy, and print culture.

Featured image: Lithograph by Charles Joseph Hullmandel after Auguste Hervieu’s ‘Frances Wright of Nashoba’ (ca. 1830).

The Met Collection: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/852838