by Lucy McDiarmid

Slightly Magical Irish Poetry and the Long 1990s examines the way recent Irish poems interrogate the status of a place or being or phenomenon considered ‘magic’.

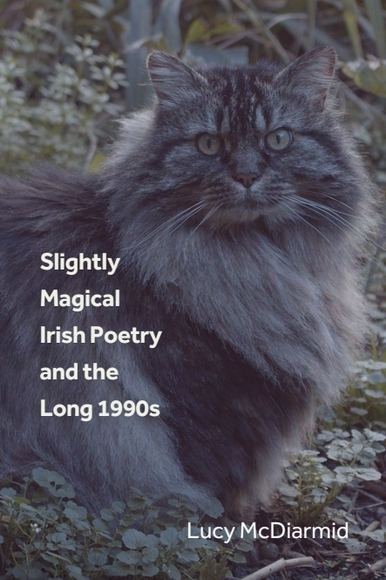

Why is there a photograph of a cat on your book’s cover?

That cat is Dora, and her human mother is one of the poets whose work I discuss in the book.

I loved the look in her eyes. It’s mysterious, eerie, uncanny, and yet the rest of the picture shows a full-bodied, actual cat, so full-bodied that her tail reaches around to the back cover.

And so she’s sort of a cat and sort of supernatural?

Exactly: she’s slightly magical, and the argument of the book is that much recent Irish poetry focuses on beings, spaces, or encounters whose ontological status cannot be definitively determined. Is the cat on the cover an actual cat, a cat sí (a cat fairy), a painting, the ghost of a cat, a stuffed animal, or some other kind of being altogether?

And what’s the answer?

There is no definitive answer. The poems I discuss play with the unstabilizable nature of their subject. That condition has long been central to Irish thinking about the world: Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill once discovered something similar in the folklore archives at University College Dublin. She found a drawer labelled ‘Neacha neamhbeo agus nithe nách bhfuil ann’ — as she translated it ‘Unalive beings and things that don’t exist’. How could that be, she wondered: ‘Either they exist or they don’t exist.’ The answer, as she soon realised, was that ‘they do and they don’t’. What interests me is that ontological ambiguity.

Is the whole book about ontologically ambiguous cats?

No, though cats are indeed ubiquitous in Irish folklore and literary traditions, in the medieval Irish poem ‘Pangur Bán,’ written by a ninth-century monk about his cat, and in the folklore about ‘The King of the Cats,’ a story of monarchical succession in the feline realm.

But the phenomenon I call ‘slightly magical’ appears in many forms. All I knew when I began this book was that I wanted to write about Irish poetry of the past 30 years or so, and as I read the work of dozens of Irish poets, I just let the ideas emerge. I discovered that the freedom of the slightly magical cast of mind, as I began to call it, appears in railroad reveries, in the tongue, rivers, hair, and encounters with strange beings, as in the case of Michael Harnett’s poem about a man who only communicates through ferns. It’s present in playful poems like Michael Longley’s ‘The Rabbit’ and serious poems like Paula Meehan’s ‘The Statue of the Virgin at Granard Speaks.’

And ‘the long 1990s’ – how do they fit in?

To explain the prevalence of ‘the slightly magical’ in that period, it’s useful to consider Ní Dhomhnaill’s ‘Ceist na Teangan’ (‘The Language Issue,’ translated by Paul Muldoon). That poem uses the story of Moses’s mother sending her baby out on the water to characterize the way the poem’s author wants the Irish language to survive through her writing: publishing her poems, she’s freely casting a ‘dóchas’ (hope) on the water for an audience somewhere, anywhere, to read. This autonomous, liberating gesture is typical of other poems in the 1990s and later in the new century: in a time when the moral authority of Church and State in Ireland was eroded, a period of scandals, tribunals, and referenda that dramatically reshaped Irish social and political life, poets were expressing feelings of liberation and release, often mixed with a note of resistance to authority. In poems written by Northern Irish poets in this period, a surreal mode often occurs, in which a reverse chronology undoes the tragedies of the present moment.

The ‘slightly magical’ ontology fits this mix of feelings because it offers new possibilities, most of them implausible but daringly inventive, moving beyond the rational and the official. Like ‘Ceist na Teangan’, many poems from this period create a space that allows an escape from repressive authorities and the freedom to critique power.

You include an unusual mix of poets in this book.

I liked the idea of disrupting the conventional grouping of poets by identity categories. This book considers poets of slightly older generations (Derek Mahon, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Michael Longley, Michael Coady, Moya Cannon, Tom McCarthy, Theo Dorgan, Bernard O’Donoghue, Paul Muldoon), poets of a middle generation (Martina Evans, Colette Bryce, Enda Wyley), younger poets (Rosamund Taylor, Annemarie Ní Churreáin), ‘New Irish’ poets who weren’t born in Ireland (Nidhi Zak/Aria Eipe, Nithy Kasa, Mimmie Malaba), poets writing in Irish (Gearóid MacLochlainn, Ailbhe Ní Ghearbhuigh, Louis de Paor) and many others.

But the book’s not encyclopedic: it’s an argument that uses the language of metaphysics to analyse the oblique way recent poems revise Irish literary traditions. And by including what the poets themselves say about the poems, even (especially) when their views are different from mine, the book exercises the same whimsical freedom that the poems do.

Thanks to Líadáin Evans, Martina Evans, Rachel Savin-Stewart, Katie Stewart-Savin, and Rosamund Taylor for permission to use their cats’ photographs.

About the author

Lucy McDiarmid’s most recent monographs are Slightly Magical Irish Poetry and the Long 1990s (2025), At Home in the Revolution: what women said and did in 1916 (2015), and Poets and the Peacock Dinner: the literary history of a meal (2014). She is a former fellow of the Guggenheim Foundation and of the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library, and an honorary member of the Royal Irish Academy.