by Stephen Harrison

Kingship and Empire under the Achaemenids, Alexander the Great and the Early Seleucids places Alexander the Great and his monarchical ideology within his Near-Eastern context.

In June 323 BCE, Alexander III died in Babylon. His conquests were so momentous that they earned him the moniker ‘the Great’ and form a transitional point in how we view the ancient world: thanks to Alexander, the Classical era became Hellenistic. Since historians have long considered Alexander a turning point, his reign has often been a point of division. Before Alexander, near-eastern history has traditionally been written by people trained in subjects like Assyriology, after him, the Near East becomes the domain of the Classicist. But this is changing. After all, to understand the impact of Alexander’s campaigns – and, indeed, the legacy of the Achaemenid Empire that he conquered – we need to write across these artificial boundaries. Did anything actually change? If so, how, and why?

Equally, how did conquering the Persian Empire affect the way that the Macedonians thought about the world? Pivotal instances – like the supposed debate about whether the Macedonians should adopt the Persian practice of proskynesis – make it obvious that Alexander and his men were affected by Persian ways of living. But how meaningful was Macedonian engagement with Persian culture? How influential were Achaemenid ideas and practices on the way that the Macedonian kings of Asia ruled?

Broadly speaking, Alexander took over the infrastructure of the Achaemenid Empire and left it intact, so we see lots of continuities here, even if there were plenty of changes too. But when it comes to imperial ideology – by which I mean the ideas and principles which underpinned governance of the empire – things are harder to assess. For instance, ‘Great King’ was an old Mesopotamian title that had been used for over a millennium before it was taken up by the Achaemenids. However, because of their prolonged contact with the Persians, the Greeks began to associate ‘Great King’ with the Achaemenid monarchy. Little wonder, then, that neither Alexander nor the first Seleucid rulers appear to have used it when communicating with Greeks. In this instance, Greek reception of a very specific aspect of Achaemenid royal ideology seems to have shaped the way that Alexander and his immediate successors presented themselves. This created a distinction between the self-representation of the Achaemenids and the Macedonian rulers, but this was made possible only because the were affected by Persian precedent. At the same time, however, ‘Great King’ was used of Alexander and the Seleucids in Babylon. Here, on this very particular point, there was continuity – and this continuity was aided by the fact that some of the material which attests to the use of the title was created by Babylonians themselves who ascribed to the Macedonians a title they had long used of their own rulers.

In the face of such complexity, and when narratives vary when we compare local and global perspectives, labels like continuity and change become largely meaningless: more interesting is how Achaemenid ideas came to be taken up by the Macedonians. Plutarch, the Roman author and biographer, paints an interesting picture of Alexander’s behaviour at Persepolis, the city at the heart of the Persian Empire. He describes Alexander wandering through the wreckage caused by the Macedonian sack of the city and stopping in front of a statue of Xerxes which had toppled over. Alexander is said to have pondered whether to re-erect the statue – one king honouring another – but eventually to have left Xerxes lying in the dirt as punishment for his invasion of Greece. This story is surely apocryphal, but it reminds us that the Macedonians were occupying places and spaces which had been profoundly shaped by centuries of Persian rule.

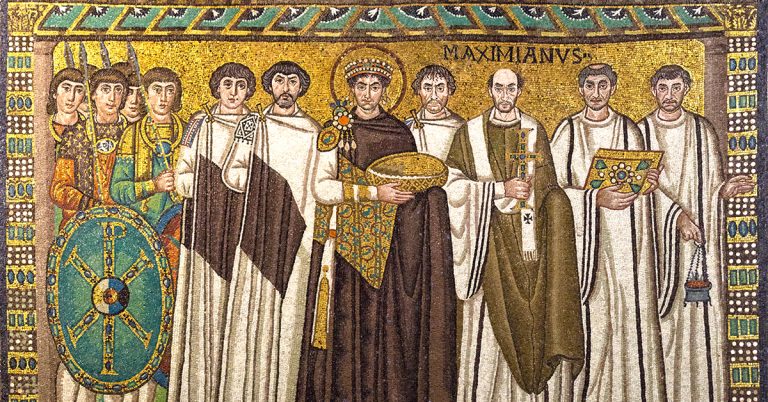

There was a cultural aspect to this, but a literal element too: initially at least, the Macedonians sometimes lived in buildings and perhaps tents which were constructed by the Persians. These structures reflected the monarchical ideology of the Achaemenid kings who had overseen their creation, and they were designed to reinforce key messages. For example, during some ceremonial occasions the Persian king appears to have reclined on a couch with golden feet, while the couches of his courtiers had silver feet. Here, the materiality of these objects created a visual distinction between ruler and subject, emphasising the king’s superiority.

When Alexander began to use this furniture, the couches introduced this messaging to his court. Simply by sitting where he sat, Alexander began to reflect a different model of kingship. When we think about cultural interaction, we often focus on the agency of people, and especially key individuals like Alexander whom we can portray as picking and choosing which bits of one culture to adopt and which to ignore. This example shows how the built environment is an actor too, superficially merely the spaces in which we live our lives, but actually instrumental in how they play out.

About the author

Stephen Harrison is Senior Lecturer in Ancient History at Swansea University. He is the author of Kingship and Empire under the Achaemenids, Alexander the Great and the Early Seleucids (Edinburgh, 2025) and Alexander the Great: Lives and Legacies (Reaktion Books, 2025).