By Elena Vanden Abeele

Elena Vanden Abeele is the author of the article ‘Frivolity and Modernity: Parasols in the Long 19th Century‘ in issue 59.2 of Costume.

When was the last time you saw someone strolling down the street with a parasol? While seeing one today is very unique, in 19th- and early 20th-century Western Europe, they were omnipresent — not only as fashionable accessories, but also as vibrant symbols of status, femininity and modernity. Here are three fascinating stories that reveal just how much meaning the parasol carried.

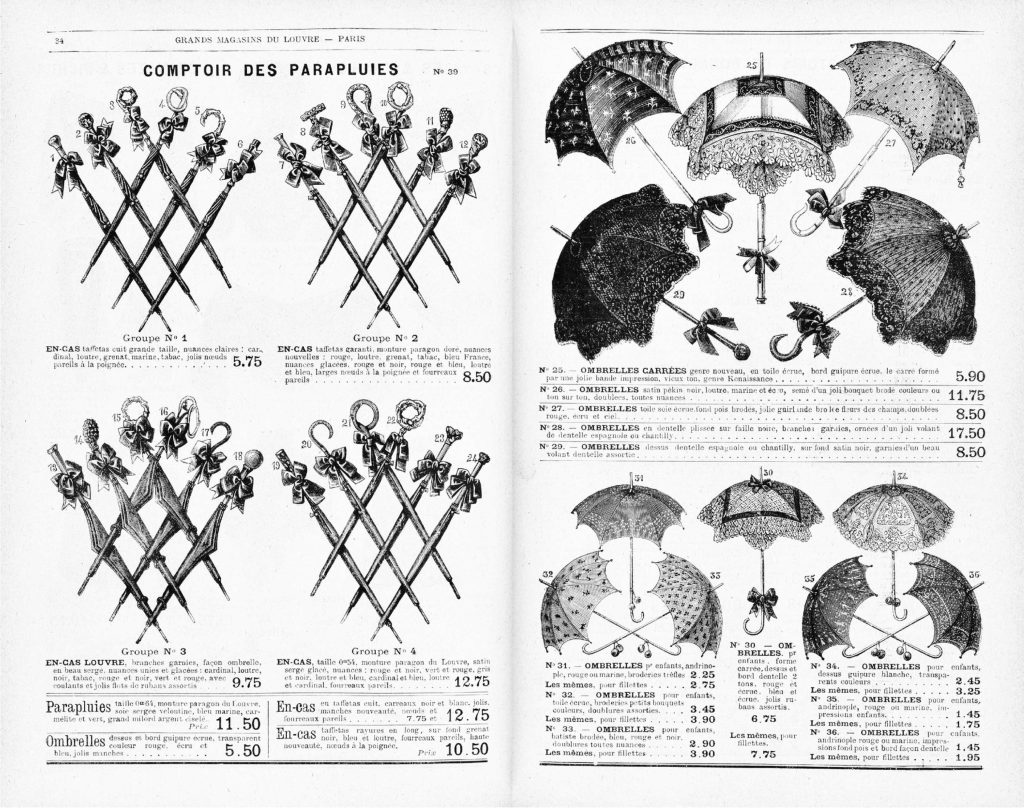

Grands Magasins du Louvre, Saison d’été, exposition générale et grande mise en

vente de toutes les nouveautés: comptoir des parapluies, 1887. Commercial catalogue.

Palais Galliera, musée de la mode et du costume, Paris, acc. no. GALCP-1887-LOU-01-vol4.1

1. The en-tout-cas: an Umbrella-Parasol Hybrid

In the second half of the 19th century, a clever accessory grew in popularity: the en-tout-cas, (or en-cas), literally ‘in any case’. As a hybrid between an umbrella and a parasol, it combined both protection against rain and sun. Combining practicality, fashionability and a nod to modern mobility, the en-tout-cas reflected a shift in how middle-and upper-class women navigated public space.

While ubiquitous today, the en-tout-cas was so entrenched in society that the accessory could even be deployed as a metaphor. In Guy de Maupassant’s 1885 novel Bel-Ami, main character Georges Duroy uses the adaptability of the accessory to describe one of his lovers’ flexible use of religion. Whether rain or shine, or social situation, the en-tout-cas resonated with the growing mobility of women in modernising society.

2. Parasols Were More Than Accessories: They Were Statements of Power and Privilege

Behind the frills and lace, parasols carried deep social meaning. They were not just fashionable accessories, but instruments of conspicuous consumption: signals of a woman’s class and respectability. The shade they provided was more than literal, symbolising whiteness, leisure and domestic ideologies in 19th-century European society.

Even the materials and decorations, such as ivory handles or Orientalist depictions, reveal connections to colonial trade and imperialism. So while they may look frivolous, parasols were embedded in complex narratives of gender, race and empire.

3. David Beckham Carried a Parasol

Yes, you read that right: David Beckham once carried a parasol. At Jacquemus’s Autumn/Winter 2023 show at the gardens of Versailles, the guests — including David Beckham — floated across in boats and were provided with white parasols. While the former midfielder may not have been aware of the complex historical baggage of his accessory, the image was striking: a global male icon holding a traditionally feminine, now re-emerging, object.

While parasols never entirely disappeared — remaining common in many Asian countries for sun protection — their re-emergence in Western fashion could signal a broader cultural shift. Could we be seeing the start of a non-gendered parasol comeback? Before that happens, why not get acquainted with the parasol’s deeper sociological meaning? For inspiration, explore the rich examples housed in two Belgian collections, discussed in my recent article ‘Frivolity and Modernity: Parasols in the Long 19th Century’ in the recent issue of Costume.

About the author

Elena Vanden Abeele is an art historian specialising in nineteenth-century fashion and textiles. She works as a research assistant for the Belgian Fashion Research Network Revers at Ghent University.

Read the full article ‘Frivolity and Modernity: Parasols in the Long Nineteenth Century‘ in issue 59.2 of Costume.

- CC0 Paris Musées / Palais Galliera, Musée de la mode et du costume. ↩︎

- Public domain, Beeldbank Kusterfgoed. https://www.beeldbankkusterfgoed.be/portal/published/c12d8687198e4adfba8be8f39b5fc09810e52fb4d4b44fb089f8894af3b11077884d971de59a4fa282c3971a398144db/details ↩︎

- © Fashion & Lace Museum (Brussels Museums); photo: Yvan Peeters. The Fashion & Lace Museum have granted permission of use in this article. ↩︎

Featured image:

La Mode Illustrée, Fashion Plate (detail), 1866. Hand-coloured engraving on paper 36,5 x 26 cm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Ac. No. RP-P-2009-3511.

Public Domain, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, gift from the M.A. Ghering-van Ierlant Collection. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/object/La-Mode-Illustree-1866-No-22-Etoffes-des-Mins–5decae46e1711d5473f671a472e6a1e5