By Chibli Mallat

Chibli Mallat is the author of Democracy Redefined, which presents a radically new definition of majoritarian democracy.

1. Tell us a bit about your book

The book is about how a constitution responds to the citizens’ expectations of a social contract that best represents them in government. Democracy Redefined is really comprised of three smaller books: the first pushes constitutional research back to the very early institutional texts in the modern Middle East, as far back as 1697, then through Egyptian rule in the Levant and the Ottoman periods; the second is the central part, which studies the formation and characteristics of the Lebanese Constitution of 1926 through the manuscripts and works of its main drafter, Michel Chiha (d.1954); and the third departs from the unusual communal system on which the Lebanese Constitution operates to challenge the received notion of democracy in a wider theoretical discussion. The book proposes a new definition of democracy.

2. What inspired you to research this area?

Pure luck. I discovered in my old files a semi-finished article of 2001 on the Lebanese Constitution, which included a reference to manuscripts which I did not have in hand then. I called a friend, Claude Asfar, who called a friend, Isabelle Doumet, who told me that these manuscripts are part of her grandfather’s archive, all available and at my disposal. The material was so rich that the treatment quickly turned it into a book, in fact a large book which Edinburgh University Press generously entertained without abridgment.

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

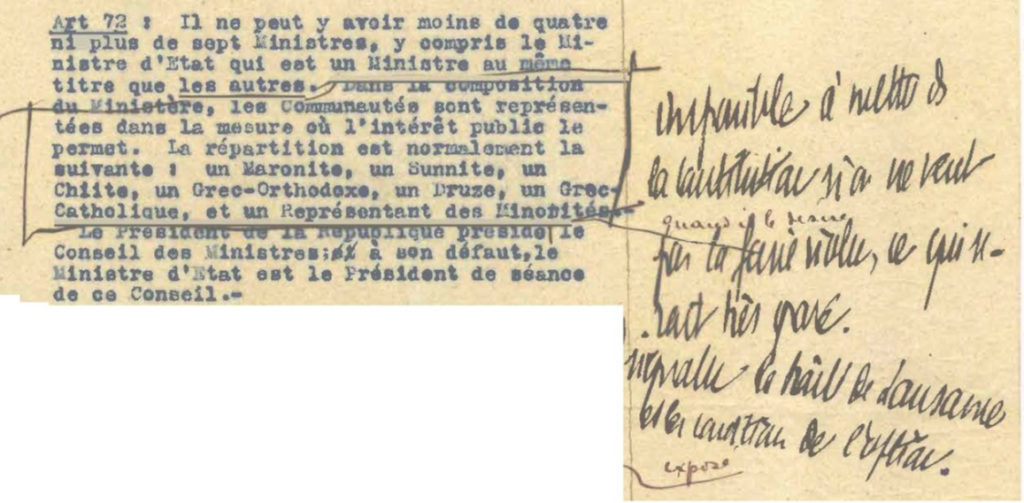

Chiha’s constitutional versions are not dated and include annotations in the margin by others whose handwriting is unknown. I was considering one such annotation on an early version of the constitutional draft. Because the comment was peremptory, and the handwriting looked ‘grand’, I suspected that it came from a higher authority, possibly the person in command in Lebanon at the time, Henry de Jouvenel, the High Commissioner under the colonial system known as Mandate. I had met his granddaughter, Anne, twenty-five years ago, in Beirut. I rang her and sent her the picture of the passage with the comment in the margin over WhatsApp:

A second later, she confirmed it was her grandfather’s handwriting.

This is a book owed to faithful and intelligent granddaughters…

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

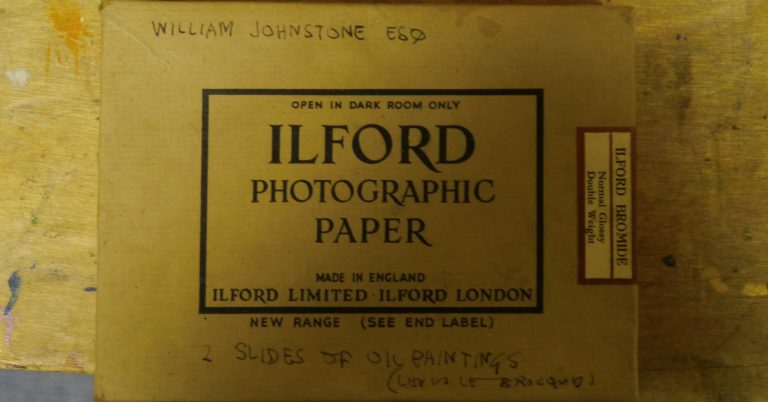

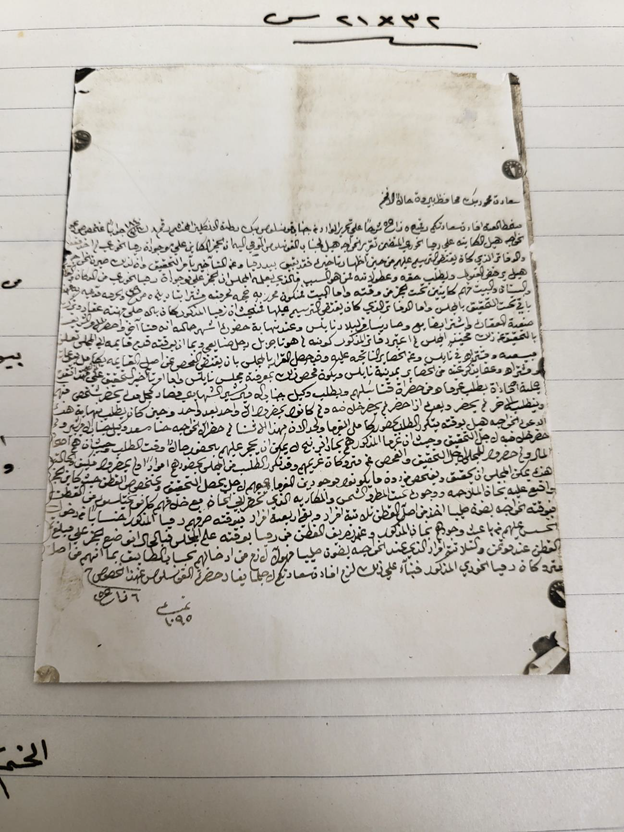

When you work on manuscripts or texts not considered previously by previous scholars, your treatment can only be novel. In a sense, this is an easy exercise of multiple discoveries, so long as you can decipher manuscripts aptly enough. And they bring you to yet other troves. Such was for me the discovery at the American University of Beirut of minutes and documents from meetings of the city’s hitherto unknown Council of Government ca 1839:

At the same time, you need to weave a ton of small discoveries into a wider picture, both historical and theoretical, within a significant worldwide scholarship available on constitutionalism and democracy.

On the theoretical side, the logic of the research pushed me into asking why the Constitution of Lebanon is the only such founding text still alive in the Middle East? And, more pithily, would such a system that protects subordinated minorities not do better than, say, the way the Black population has been treated by the white majority through three centuries of American constitutionalism?

Has your research in this area changed the way you see the world today?

Yes. Concluding that democracy needs to be redefined is quite the challenge, and I did not take it lightly. I had the privilege of discussing some of these conclusions with a leading theoretician of political science, Jane Mansbridge, and I considerably changed the last two chapters in the light of extensive discussions with her. To conclude, as I do, that a complete, full, real democracy is contingent on representing historically subordinate groups in a constitution, is a strong and fraught proposal. I hope that my new definition is vindicated in the longer course of the human arc of justice.

What’s next for you?

The present book is published with a companion book by the Chiha Foundation, which is a beautiful full set of facsimiles of Chiha’s Constitutional Papers, with short introductions and a research guide which I wrote for the larger public. I also completed a project which took a very long time, on another major figure of Lebanese thought, the Shi‘i leader Musa al-Sadr, who was invited to Libya by Muammar Qaddafi and subsequently disappeared there in 1978. It is being published by the prestigious Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought series, which puts Sadr right up there with great political thinkers of Condorcet and Kant caliber.

I am hoping to take a break after more than ten monographs and some forty edited volumes, to repair the overly English nature of my scholarship. I will be mostly working on translations of several of my books for the Arab public.

About the author

Chibli Mallat is an international lawyer and Emeritus Presidential Professor of Law at the University of Utah. He is the author of some twelve monographs, including Introduction to Middle Eastern Law (Oxford UP 2007, 2009); Philosophy of Nonviolence (OUP 2015), The Normalization of Saudi Law (OUP 2022) and has advised several groups and governments in the Middle East over constitutional reform. Mallat taught at various universities in three continents, including Harvard and Yale law schools, Princeton, the University of Lyon and the Islamic University and Saint Joseph’s University in Beirut. He was senior visiting scholar at the school of law at Sciences-Po in Paris for research on the present book.