By David Peters, PhD

David Peters is the author of ‘James Wilson’s Reidian Revolution Principle‘ in Issue 23.1 of the Journal of Scottish Philosophy.

What does the US Constitution mean? What does democracy entail? Do these questions overlap? For answers, many Americans look to the Framers, the men who wrote the US Constitution and the sources they drew from. Locke is normally seen as the primary influence, leading some to assert that the US is a republic as opposed to a democracy. Yet, Scottish-born American Founder James Wilson’s radically democratic and revolutionary answers to these questions challenge this understanding.

These answers can be found in his significant contributions to the US Constitution and resulting political theory. Answers that hold potentially profound implications for our understanding of the US Constitution and contemporary politics.

Who was James Wilson?

While often forgotten, Wilson was far from a minor character in the American Founding and Early Republic. He signed both the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution, even helping pen those famous words: ‘We the People.’ He would later serve as one of the first Supreme Court Justices. And, according to Aaron Knapp: ‘Wilson’s law lectures gave birth to American jurisprudence as such.’1

Importantly, throughout these contributions and in his political theory, Wilson broke from Locke. Instead, he relied on the philosophy of Thomas Reid, a leading figure in the Scottish Enlightenment. Wilson’s Reidian political theory provides a radically democratic interpretation of the US Constitution where democracy is reconceptualised as a continuous progressive revolution.

Wilson’s Reidian Revolution Principle

At the heart of Wilson’s contributions and theory is his Revolution Principle. This principle states that, through democratic means, the people can change any aspect of their governance at any time and for any reason, precisely because the people are and remain sovereign.

As I explain in more detail in my article for the Journal of Scottish Philosophy, Wilson’s principle is grounded in Reid’s philosophy. To identify the people as sovereign, Wilson looks to Reid’s dignified conception of humanity and particularly their capacity to self-govern. He also adapted some of Reid’s critical techniques and tests for first principles to identify his Revolution Principle as a Reidian first principle. And thus, according to Wilson it is ‘an inalienable right of the people’ and moreover, a right ‘of which no positive institution can ever deprive them’2

Is the Revolution Principle in the US Constitution?

According to Wilson, his Revolution Principle is central to the US Constitution. He located it in the Preamble and the act of popular ratification. Wilson saw popular ratification as his principle put into practice. Through a popular vote, the people had abolished the Articles of Confederation and instituted a whole new federal government outlined in the US Constitution.

Moreover, Wilson’s interpretation was the only one that could effectively deal with the most difficult obstacle to the US Constitution’s ratification: the problem of divided sovereignty. The problem was whether the federal or state governments would be sovereign under the new constitution. Wilson answered that neither would be. Rather, the people are and would remain sovereign, able to alter the constitution and government at will. This allowed for growth and flexibility, while also removing the fear of being trapped in a bad contract.

Re-evaluating the US Constitution

Wilson’s contributions and theory challenge many of our conceptions about the US Constitution. Not least among them is its Lockean foundations and the corresponding underestimation of Reid’s and the Scottish Enlightenment’s significance.

In the ratification debates, Wilson rejects the notion that the US Constitution represents a Lockean contract. This contract entails the people consenting to give up their own sovereignty in order to form a sovereign government. Wilson likens this to a people willingly enslaving themselves, highlighting the inherently monarchical or authoritarian aspects of this theory.

Even Locke’s revolution principle did not sufficiently address these concerns and respect the people’s sovereignty. Locke’s principle requires a breach of contract to devolve sovereignty back to the people. Violence is then required to realise a revolution, which simply establishes a new sovereign government. Alternatively, Wilson’s Reidian Revolution Principle recognises the people’s perpetual sovereignty, effectively democratising and legalizing revolution, rendering it peaceful, legitimating and progressive.

This certainly challenges our historical understanding and modern interpretation of the US Constitution. But also, more importantly, how we think about what democracy entails. In Wilson’s vision of democracy, government is a tool of the people. One which they could and should continually improve—or revolutionise—through democratic means to suit their needs and respond to the problems society faces. For Wilson, democracy is (or should be) a continuous progressive revolution in governance.

Recovering Wilson certainly puts calls for democratic, structural, and constitutional reforms in a more positive light. Yet, on a deeper level, a Wilsonian re-conceptualisation of democracy might help us transform unaccountable and unresponsive governments into tools of the people. And, if it does, we’ll have Wilson, Reid and Scotland to thank for it.

Read the full article, ‘James Wilson’s Reidian Revolution Principle‘ in the Journal of Scottish Philosophy

About the author

David Peters is a lecturer in history, politics, and law, most recently at The American University of Paris. He holds degrees from the University of Edinburgh (MSc), and the University of Glasgow (PhD). His research traverses history, politics, philosophy, and constitutional law. It primarily focuses on the Scottish Enlightenment’s influence on the US Constitution as a means to understand and potentially address contemporary political and social issues in the US and further afield. He is currently working on a monograph that delves into American Founder James Wilson’s reliance on the philosophy of his fellow Scot, Thomas Reid, in the formulation of his revolutionary Democratic Political Theory.

Footnotes

- Aaron T. Knapp, ‘Law’s Revolution: James Wilson and the Birth of American Jurisprudence‘, Journal of Law & Politics, Issue 29.2 (2014): 194. ↩︎

- Respectively: John P. Kaminski, Gaspare J. Saladino, Richard Leffler, Charles H. Schoenleber and Margaret A. Hogan, ed, The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution Digital Edition (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009), 2:472; & Jonathan, ed. Elliot, The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution as Recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia in 1787: Together with the Journal of the Federal Convention, Luther Martin’s Letter, Yates’s Minutes, Congressional Opinions, Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of ’98-’99, and Other Illustrations of the Constitution, Vol. 2 (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1941), 2:432. ↩︎

Image credits

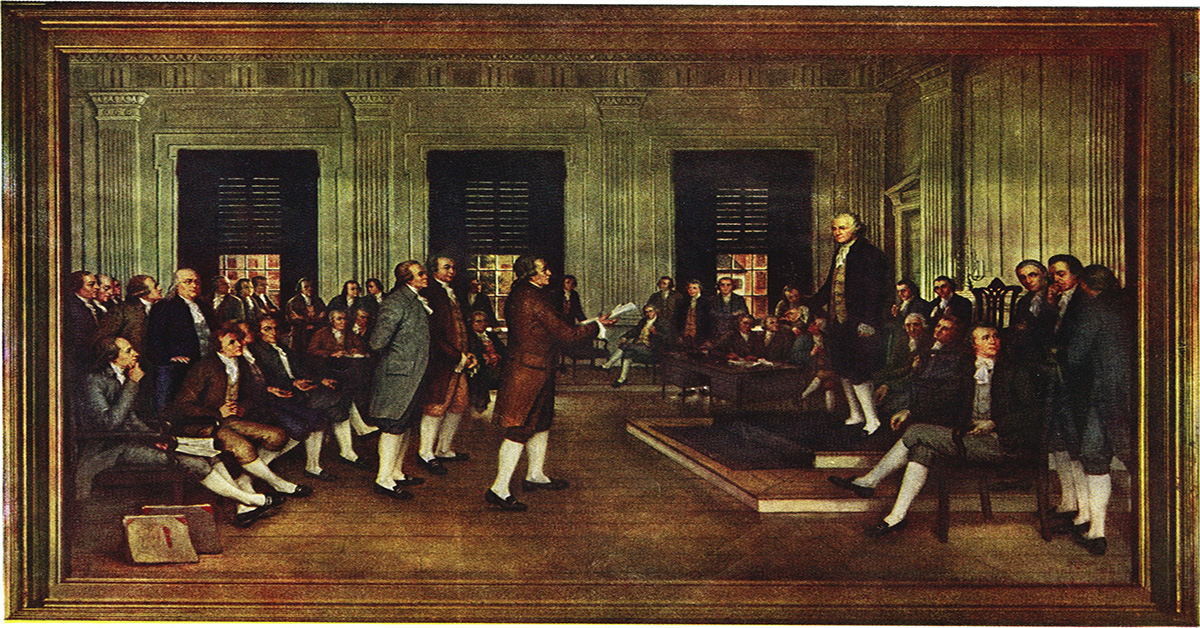

- Featured image: ‘The Adoption of the U.S. Constitution in Congress at Independence Hall, Philadelphia, Sept. 17, 1787’ (1935), by John H. Froehlich: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%27The_Adoption_of_the_U.S._Constitution_in_Congress_at_Independence_Hall,_Philadelphia,_Sept._17,_1787%27_(1935),_by_John_H._Froehlich.jpg

This painting by John H. Froehlich in 1935 hangs in the Pennsylvania State Museum in Harrisburg. According to N. Lee Stevens, the senior curator of art collections at the State Museum of Pennsylvania.