by Sarah Churchill

Sarah Churchill is the author of ‘Domestic Documents: Contemporary Photography and the Irish Housing Crisis‘ in Issue 55.1 of the Irish University Review.

In 2022, British surrealist Henry Orlik was evicted from his flat in a London social housing estate while in hospital. His personal possessions, including seventy-eight artworks, have yet to be recovered. Reading of Orlik, I was reminded how important safe and affordable housing is to a thriving art scene. (After all, where would the New York School have been without gritty Greenwich Village?) In my recent article for the Irish University Review, I consider the real and imagined landscape of home in Irish art and its relationship to Ireland’s housing crisis. It’s got me thinking – what will become of the Irish art scene if things don’t improve?

As it turns out, the artists I spoke with for this research shared my concerns for the future. According to artist and filmmaker Aideen Barry, housing is the quintessential issue facing Ireland today. Barry’s own preoccupation with home, which emerges in works like Levitating (2007) and Possession (2011), is deeply personal. ‘Home is like a trench in my work’, she explains, ‘It’s supposed to be the space of safety and security but often it’s the space of turmoil and angst’. Whether taking aim at Ireland’s regressive legislation of women’s domestic labour in its constitution or lamenting a national obsession with property ownership, what emerges in Barry’s approach to this theme is her appreciation of housing insecurity as a political rather than a personal failing. ‘We’ve missed a trick by not enshrining in our constitution the home as a human right’, she’s observed, ‘even in the centenary of the signing of the proclamation, we didn’t revisit what was in our proclamation and here we are nearly ten years on, and housing has become the most volatile conversation in Ireland’.

The absence of leadership on the housing issue has been similarly noted by artist and activist Adam Doyle, also known as Mála Spíosraí or Spicebag, whose controversial digital collage The Eviction (2021) is a stinging indictment of Ireland’s laissez-faire housing policy. As Doyle notes, the high cost of housing disproportionately impacts emerging artists. He described to me a situation in which a simple housing search required hundreds of inquiries and a fierce competition with families and wealthy tech workers. ‘In Dublin, all the people are competing for the same house. It’s not like that in Glasgow, London, or Belfast’, Doyle observes, ‘It’s grim’.

In his view, the lack of housing, ‘stifles the creative wing from which change emerges. The same circuit of musicians and artists that are already established, the golden circle, they’re fine. But anyone on the edge would sort of struggle. It stifles new creativity and reinforces the status quo’. Cheap real estate, of course, is essential to struggling artists, who rely upon the creative communities such neighborhoods initially attract. Such enclaves are now non-existent in Dublin. Frustrated, Doyle’s left Ireland and has been living abroad for the last several years.

The home, now a luxury item in Ireland, is beyond the reach of most young people. The frustration is helping to mobilize a dangerous rightward shift in Irish politics, as Barry and Doyle each noted. Over the past several years, the political exploitation of immigration and housing shortages as linked issues has sparked protests and frightening incidences of arson designed to intimidate immigrant communities. Doyle worries that too many in the government are happy to blame others for their mismanagement, particularly given their own entanglements in the Irish property market. According to a 2024 report in The Irish Times, nearly a quarter of Ireland’s elected representatives in the Dáil Éireann (the Irish parliament) own rental properties. Of these, the largest property owner, TD (Teachta Dála) Michael Healy-Rae, owns some twenty-five properties, some of which were listed as vacant at the time of the report.

With chronic inventory shortages, poorly constrained landlordism, and rising prices, homelessness is at a record high and emigration by Irish citizens is again on the rise in Ireland – a distressing set of circumstances for anyone longing to call Ireland home. But these are just the most visible consequences of housing crisis. Many more hidden costs, from poor mental health to lost economic opportunities, are harder to quantify. There are no graphs that can convey what housing crisis feels like on the inside. And when it comes to the question of home, feelings matter more than we realize. That’s why in my own research I’m looking beyond the raw data. Rather, I’m looking to artists – and to their art – to tell that story.

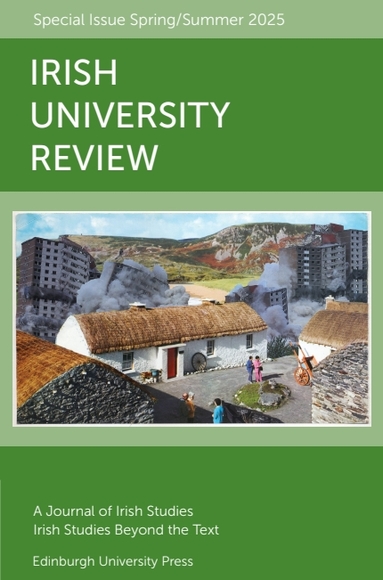

Journal cover image:

Sean Hillen, ‘Searching for Evidence (of Controlled Demolition) at Father McDyer’s Folk Village, Glencolmcille, Co. Donegal’, photo collage, 2010

About the author

Sarah Churchill is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. Her essay ‘Domestic Documents: Contemporary Photography and the Irish Housing Crisis’ is part of the special issue of Irish University Review published in May 2025: Irish Studies – Beyond the Text.

Adam Doyle is an Irish artist and political commentator working under the moniker ‘Spicebag’. Doyle’s work around Irish culture, politics and Palestinian solidarity has garnered international coverage. Follow him on Instagram: @spicebag.exe

Aideen Barry is a Visual Artist, Film Maker and Academic based in Ireland but with an international profile. Her works are in major public museum and private collections all over the world. She is a member of Aosdána and the Royal Hibernian Academy. www.aideenbarry.com