By Douglas Cawthorne

Douglas Cawthorne is the author of the open access article ‘A Maritime Compass Petroglyph in Shetland‘ in Northern Scotland.

Trade tariffs in geo-politics are not new. They were used by north European countries in the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries to control maritime trade networks and to exclude competitor nations from lucrative sources of raw materials and processed goods, often as an extension of political and military policy. Very often there is little physical evidence of this trade, however my article ‘A Maritime Compass Petroglyph in Shetland’ points to the West of Shetland, where there are records of tariffs being used to control the supply of goods in this way.

A legacy of Norse laws

The Norwegians and then the Danes exercised trade tariffs for centuries in a policy called the ‘mare clausum’ or ‘closed sea’ over the Faroe Islands, Orkney, Shetland, Greenland and eventually Iceland, which they collectively called their Western tax-lands or tributary islands (skattelande). From at least the mid-fourteenth century onwards, North German merchants of the Hanseatic league called Bergenfahrer paid trade tariffs to the Norwegian-Danish crown for a monopoly, giving them exclusive access to the products of these islands.

Like the other tributary islands, Shetland had Norse laws and customs but this began to change when first Orkney in 1468 and then Shetland in 1469 were ceded by king Christian I of Norway and Denmark to King James III of Scotland. Norse laws largely remained in Shetland until 1611 when Bishop James Law, acting as kings commissioner for the islands, brought them fully under the law of Scotland. Foreign merchants arriving in Shetland frequently had to pay heavy tariffs to the new Scots landowners or ‘lairds’ for the right to anchor off and trade on their shorelines.

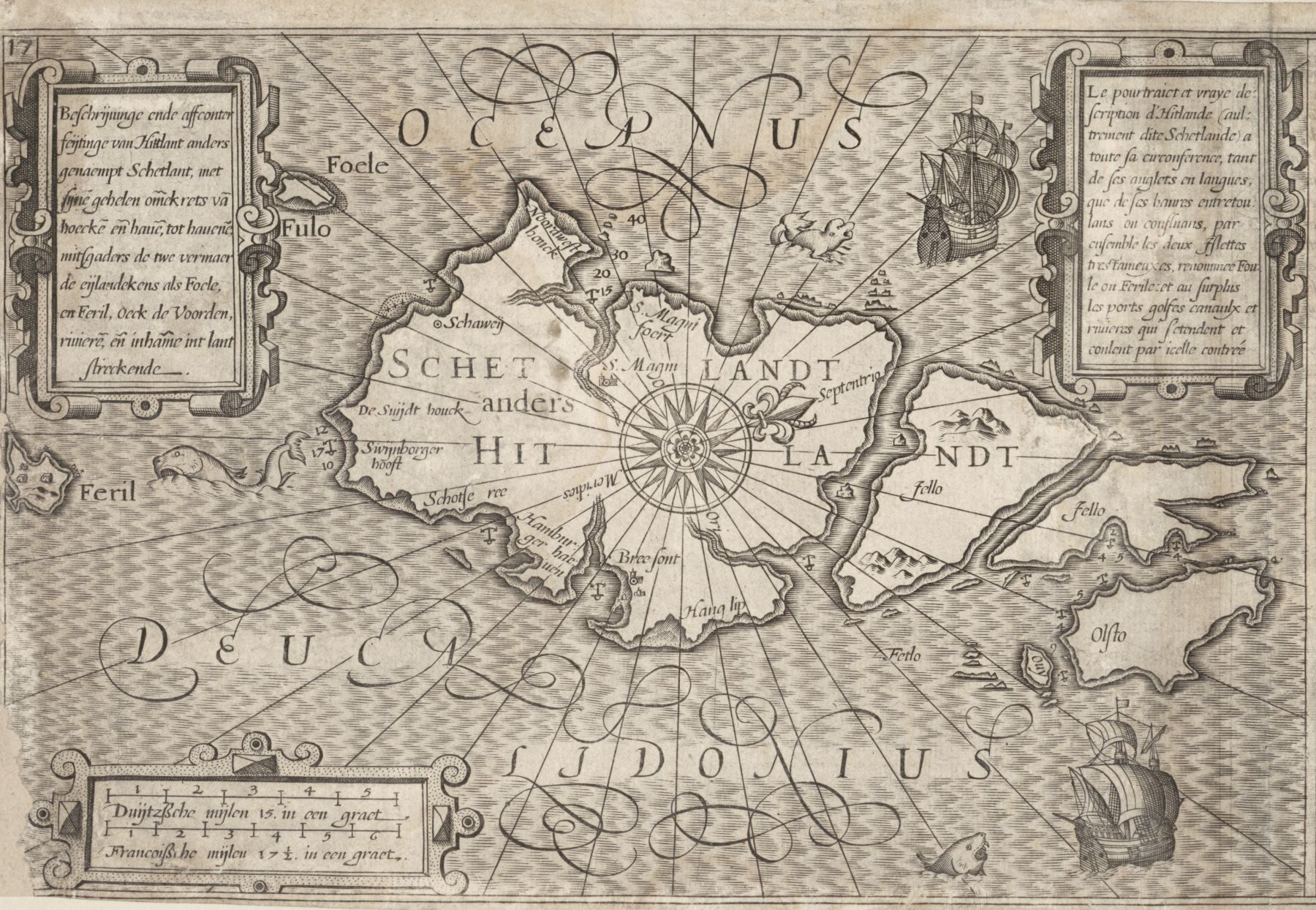

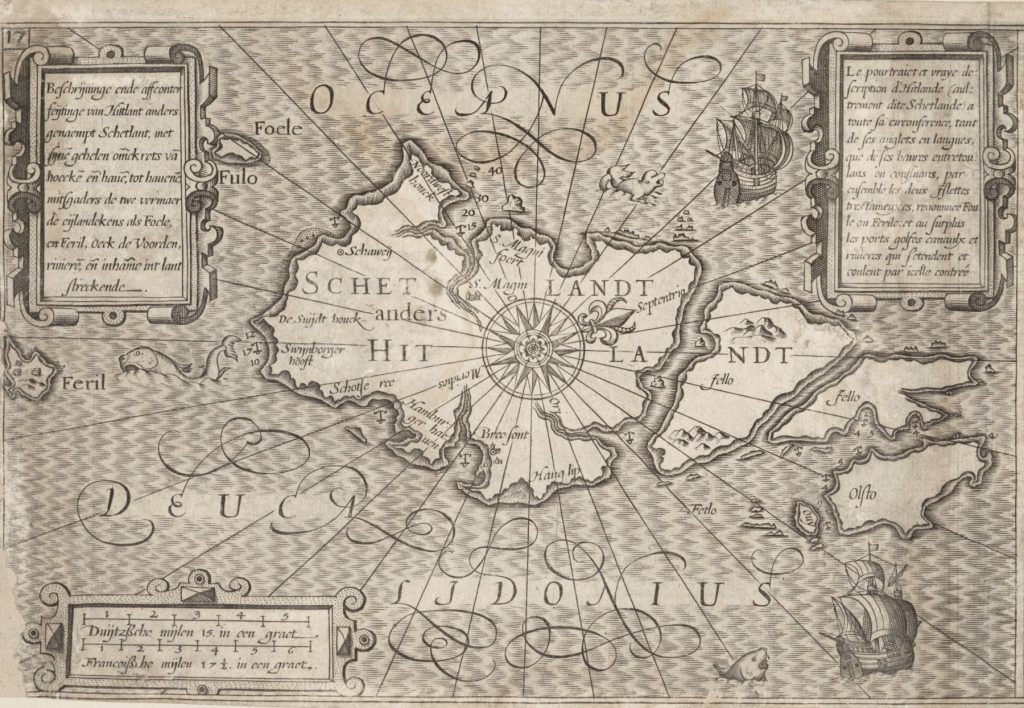

From Thresoor der Zeevaert by Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer

Changing customs and shared traditions

The Scots presence in Shetland also began to shift trade to ports in Scotland rather than Norway and up until 1702 there developed a triangular North Sea trade network between Shetland, North Germany and Scotland. Scottish and Shetland merchants and seamen sailed on North German and later Dutch ships and participated in this trade and its navigation. In doing so they would have been exposed to North German and Scandinavian maritime trade and navigation practices. One of the more curious of these was carving compass petroglyphs in rock, most often on high-points at havens and anchorages. Examples exist on rocks from western Sweden to Northern Norway, on the coastlines of the Baltic Sea and White Sea and even as far west as the Faroe Islands. Nearly all date from the 15th to the early 18th centuries and are aligned more or less accurately with north. They are also often accompanied by carved merchants’ marks, initials and sometimes coats of arms. This might point to their role as symbols, perhaps of possession or recognised locations of trading rights in the surrounding area and rights to, or payments of, tariffs. Other purposes are quite possible since in this period there remained much mystery surrounding the navigator’s art. The magnetic compass in particular held an almost supernatural fascination which lent it an aura of importance for mariners, paving its way into wider culture and iconography.

The enduring mystery of the petroglyph

To date, there is only one known example of a compass petroglyph in Scotland and that is in the Shetland Islands. Like its counterparts in Scandinavia, it is enigmatic, it is surrounded by carved initials and it is also very probably the product of this early modern maritime trade with Northern Germany and Scandinavia. My article ‘A Maritime Compass Petroglyph in Shetland’, published in the EUP journal Northern Scotland, examines this particular remnant of an important international maritime trade network. It looks at this compass petroglyph’s unique characteristics, its potential date and its local and wider historical context including trade tariffs paid by German merchants close by. These were important in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries because there was significant competition for the best harbours, anchorages and trading sites in Shetland where stockfish (dried fish) and later clipfish (salted fish) including herring could be bought, processed and transhipped most easily. Exclusive possession of favoured anchorages and surrounding shore-side trading sites in the islands in return for payment of tariffs to the local laird would have been a key determinant of the financial viability of a merchant’s trade voyage. This was not least because payment could be made in-advance to secure a site for the following season and access to the locally produced goods at that site.

It would have been natural in these circumstances for traders to want to place their imprimatur on such a place to signify exclusive, enforceable and authoritative possession and this is perhaps one of the possible functions of a maritime compass petroglyph in Shetland. Nevertheless, this is not the only possible interpretation of its purpose and it may have had others. What do you think?

Read the full article, ‘A Maritime Compass Petroglyph in Shetland’ in Northern Scotland

About the Author

Douglas Cawthorne is an independent researcher, architectural historian and Scottish yachtsman. His background is in university teaching, contract research and digital heritage. He is author of the book, ‘The McGruer Lorne Class Yachts’ (Scotforth, 2013).

Explore related articles on the EUP Blog

The lost story of the Shetland Female Emigration Fund

Fr John Morrison: defender of an island’s cultural heritage and faith