By Nicole Maceira Cumming

Nicole Maceira Cumming is the author of the article ”Whether or not there be any difference between men and beasts …?’: Animals, Dominion and Natural Law in Post-Reformation Scotland’ in Scottish Church History.

My research is concerned with how people thought about and interacted with animals in early modern Scotland. Dogs are often labelled as ‘man’s best friend’1 and their dominant presence in the historic record reflects this status. Dogs were, after all, one of the domestic animals which lived and worked most closely with humans. Yet, the traces they leave also reveal the varied ways in which dogs occupied early modern spaces and minds.

Royal hounds

James VI (1566-1625) of Scotland loved to hunt and kept many hunting dogs in his court. Insight into their lives can be gained from the ‘houndis compt’ (kennel accounts). These accounts (NRS, E22/12-14) reveal what the dogs were fed, the cost of coal and straw to keep the dogs bedded and warm and expenses such as soap to clean them.

Dogs were also given and received as gifts. Ten deerhounds were sent to ‘our deerest bruder the King of Denmark’ in August 1594, accompanied by the three falconers who had been appointed to care for them, a trumpeter and all the necessary supplies for the journey. Royal dogs were highly valued and cared for; their lives were arguably better than much of the human population!

Canine accomplices

In February 1616, George Scott, a shoemaker in Hawick, was on trial for the slaughter of the Laird of Drumlanrig’s sheep. The trial records that he was accompanied by his dog who, rather amusingly, was named Hyde-the-bastard. But this was clearly not a name given out of any dislike for his companion, whom George called his ‘bastard brother’ (pp.382-384).

Another account from 1574 reflects the lengths that some would go to to protect their canine companions. The case, recorded by the Privy council, involves Andro Makky, Edmound Broun ‘ane Hieland piper’ and his dog. The dog is said to have bitten Makky, resulting in him bleeding profusely. Makky then struck the dog, leading Broun to attack him with his sword, sending him fleeing (pp.418-419). Man’s best friend indeed …

Nuisance dogs

After James Stewart, Earl of Arran, was murdered by James Douglas of Parkhead in 1595, his body was left ‘in an open kirk … and was found eaten with dogges and swine’ (pp.198-199). In this period stray or wandering dogs, who did often congregate in kirk yards, were a common source of concern.

In 1655 ‘great flesher [butcher] dogs’ in the parishes of Culross and Tulliallan were said to have caused ‘great hurt and skaithe [harm] … to several persones and bairnes within [the] burghe’ (pp.278-279). And in this same area, great concern was raised in 1733 about ‘some wood [mad] dogs going through town.’ The dogs were believed to have rabies and to protect the inhabitants of the area, a decision was reached not to ‘suffer any dogs’ to live (pp.103-104). A rather sad reminder of the threat which disease could pose.

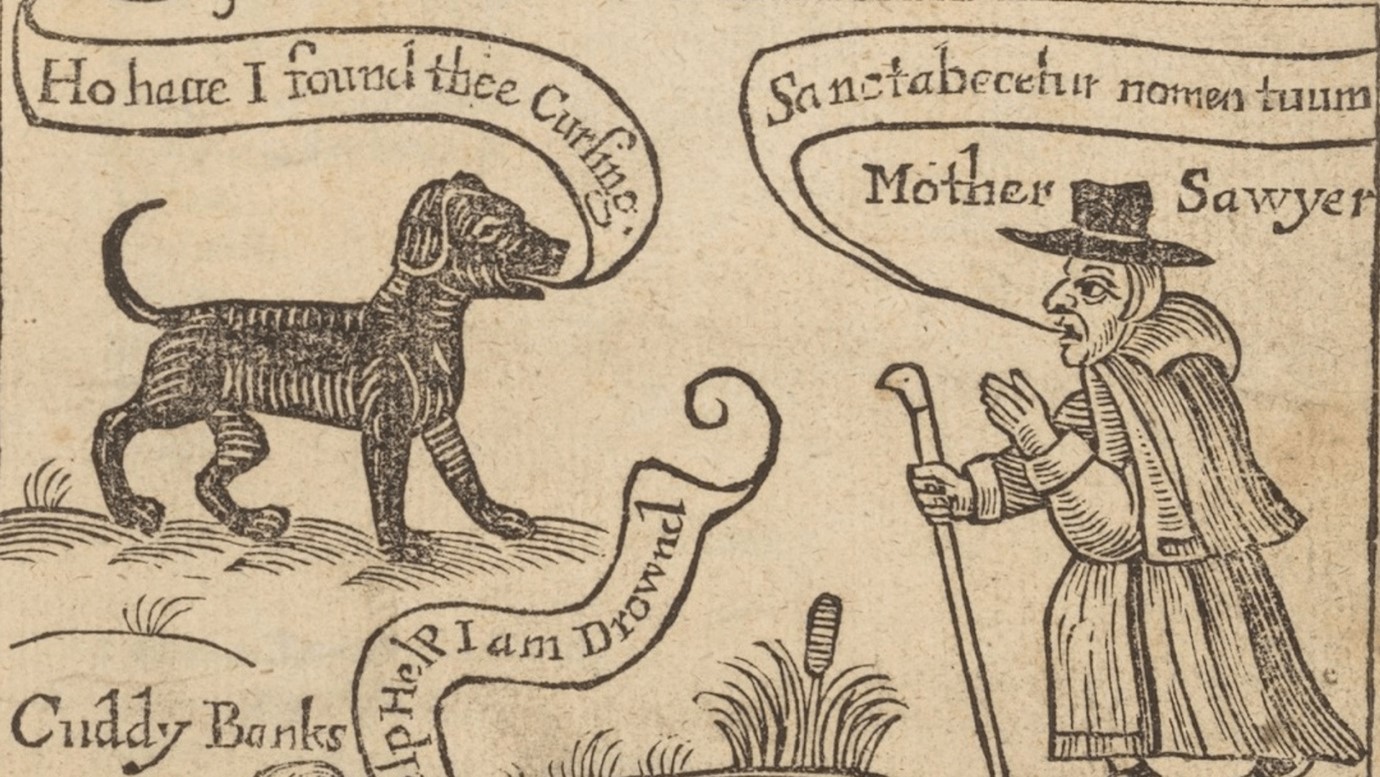

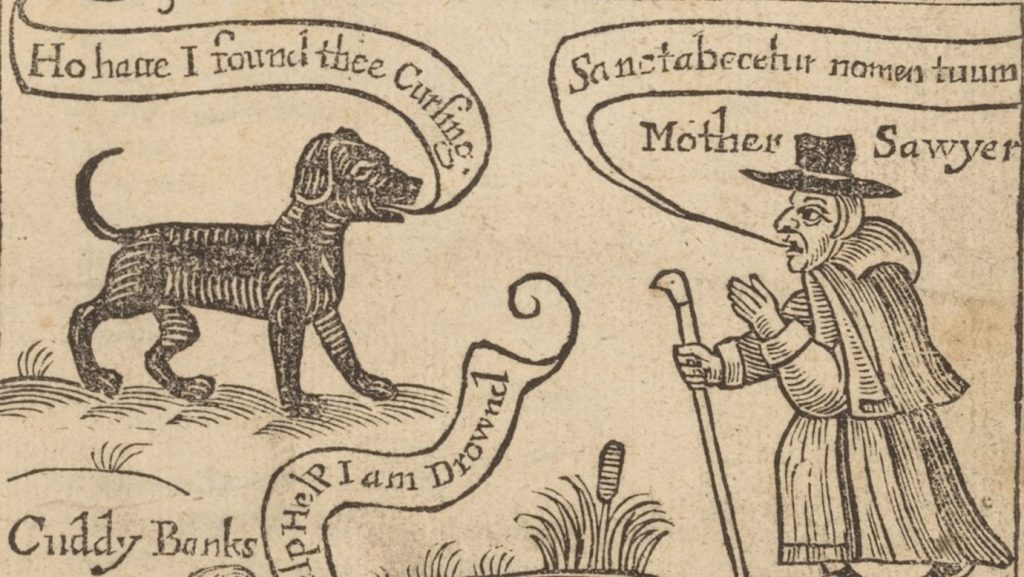

Demonic appearances

There are two predominant places where we come across dogs in the Scottish witch trials. They were the second most common animal, after cats, that a witch was believed to be able to transform into, and they were the most common animal form that the Devil was said to take.

In the 1597 Aberdeen trails, Jonnet Wischert was said to have taken the likeness of ‘ane broun tyk’ and attacked her son-in-law John Allan in response to him having assaulted his wife, Janet’s daughter (pp.88-89). Similarly, in the 1608 trial of Beigis Todd the accused was said to appear each day before Alexander Fairlie in the shape of a dog, putting him ‘almaist out of his witts’ (pp.542-543) and in another trial of 1649, Jeane Craig was said to appear as both cats and ‘uglie black tyks’ in the homes of John Barbes and James Cowan (NRS, JC26/13/B/10, item.6). It is clear that dogs and other animals could often be suspected of diabolic association.

Slanderous insults

In The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedie, the Scottish poet William Dunbar (c.1460-1530) calls his opponent a ‘crabbit, scabbit, ill-facit messen-tyke’ (pp.73). The poem is full of comedic insults but the reference to him as a ‘messen-tyke’ (ill-bred lapdog) is notable. Unlike hounds used for hunting, who were associated with noble war-like behaviour, lapdogs were understood to epitomise feminine traits, and the relationship between human and pet was often portrayed as perverse.

The dog also often found itself commonly linked to sinful fallen human behaviour in post-Reformation Scotland. The minister John Wemyss (c.1579-1636) wrote that through ‘sinne he [man] becomes a beast, like a dog’ (pp.233). A more in-depth discussion of the place of animals within post-Reformation Scottish thought can be found in my recent article in Scottish Church History.

The varied ways in which dogs appear in the record reveals a multifaceted image of our canine companions, as both ‘man’s best friend’ and his enemy.

- In reference to this common phrase, and in line with the language of the early modern period, the gendered language of ‘man’ (meaning human) and his/him will be employed intentionally throughout this post. ↩︎

- The Witch of Edmonton, a play by William Rowley, Thomas Dekker, John Ford & c. (printed by J Cottrell, London, 1658). Houghton Library, Harvard University, 14433.26.13 via Wikimedia Commons ↩︎

Read the full article, ”Whether or not there be any difference between men and beasts …?’: Animals, Dominion and Natural Law in Post-Reformation Scotland’ in Scottish Church History

About the author

Nicole Maceira Cumming is a Teaching Fellow in early modern history at the University of Edinburgh. She recently completed her AHRC-funded PhD thesis, which examined the role of hunting in the Scottish court of James VI, c.1579-1603.