The legacy of Byzantium and the role of transcendent justice

By Michail Theodosiadis

Ancient Greek Democracy and American Republicanism traces the remnants of Ancient Greek democratic thought in American Republicanism

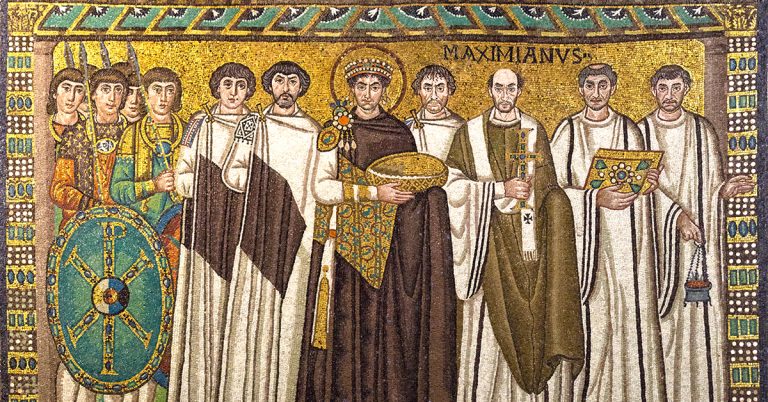

In 2013, Adrian Pabst published a groundbreaking article, challenging the conventional view of the Byzantine Empire as an absolutist theocracy, starkly juxtaposed to Western secularism and liberalism. Early Byzantium, he argued, was an alliance of city-states bound by shared culture and faith; Byzantine emperors and priests were regarded as earthly representatives of Christ, embodying a vision of secular power profoundly shaped by religious ideals that emphasised the universal good and collective well-being. Hence, Byzantium was a cosmopolitan politeia (or a cosmo-politeia); it was a structure that united (and protected) Greek-speaking city-states, forming a large political entity. The Greek historian of political thought, Georges Contogeorgis, also spoke of the koina (or commons), that is, of popular associations in many Byzantine cities. Here Contogeorgis refers to the Byzantine/Roman principle of local self-government (αυτοδιοίκητο), which ensured a degree of political inclusion.

Furthermore, Pabst mentions Saint John Chrysostom, who claimed that Christians must not reject the public and political realm; instead, they should judge secular rule based on divine norms of justice. Chrysostom feared that conflating the sacral with the secular would lead to the deification of human rulers, effectively turning them into idols. Likewise, the secularization of sacral power could lead to a despotic takeover, as indicated by Byzantine critiques of Popism (highlighted by Sir Steven Runciman). This suggests that Byzantium’s legacy is one of balanced cooperation (συναλληλία) between religious and secular authorities. We understand, then, that the sacred should serve as a moral source of critique of political power, ensuring secular fairness and social/political justice. Let us examine how this legacy offers untapped potential for building a unified European community beyond the failures of the liberal market system (as Pabst also believed).

The Promethean and Pontifical human in Byzantine society

Considering the deeply ingrained religious fervor in Byzantine public life and experience, we could suggest that this emphasis on justice, deriving from transcendent values, was likewise embedded in the temperament of the people. This conclusion is ardently supported by Anthony Kaldellis, who also shed light on procedures through which laws imposed by imperial authorities were rooted in public customs. We could, therefore, call the Byzantine society Promethean. More to the point: political Prometheanism, as I explain in Ancient Greek Democracy and American Republicanism, advocates the inclusion of the people in political structures. This could occur not just through democratic procedures; for consensus-based law-making and/or involvement in local affairs (according to the example of the Byzantine commons) also applies. By considering Seyyed Nasr’s ideas, we could claim that the Byzantine world was also ‘Pontifical’. For the same author, the Pontifical man creates bridges between the sacral and the secular. This is what we find in Chrysostom’s conceptions of justice, which direct our attention to sacral realms and transcendent norms in order to check and balance secular authorities. Thus, both the Promethean and the Pontifical human coexist in the Byzantine context.1

Pabst calls the European Union a ‘neo-medieval’ entity and (partially) attributes the existence of civil society institutions that protect the citizenry from arbitrary power to the Byzantine Christian heritage. However, he assumed that Europe had been usurped by technocratic bureaucracies and financial monopolies in the context of the spread of ‘neoliberal’ capitalism. Consequently, a centralised European superstate emerged, ultimately devouring the autonomy of individual nation-states and leading to a dangerous imbalance of power that severely undermines the principles of subsidiarity and self-determination. In response, Pabst supports the ‘rediscovery’ of the roots of this ‘neo-medieval’ structure in Byzantium. He ultimately questions approaches that consider secularism as a necessary prerequisite for freedom and justice.

Reviving transcendent values for modern justice

We could, therefore, assume that the revival of a project which follows the legacy of the Byzantine ‘Promethean’ cosmopoliteia first and foremost presupposes the resurrection of the Pontifical human and, thus, the rediscovery of the concepts of divine moral order and truth. These concepts (according to Saint Chrysostom) should guide human societies against the selfishness of secular overlords. Western modernity assumes that transcendent values are not important to promote common decency; the people can rely on their supreme power of reason alone, internalising concepts and norms of justice. This argument has been supported by a good deal of radical thinkers (to the likes of Cornelius Castoriadis), who often neglect that liberal conceptions of justice originating in religious morals have been secularised and internalised by Western societies. Transcendent values safeguard this sense of moral decency by aligning its content and objectives with the universal good, firmly rooted in the power of cosmic order. Thus, we could assume that the desiccation of religion in the West destroyed the extrasocial basis that provides such a powerful anchoring for secular justice, leaving political and social structures susceptible to the unchecked ambitions of ruling elites as well as to technocratic usurpation. In this regard, the Promethean shift of Europe from a centralised superstate towards a cosmo-politeia, which respects the autonomy of each nation, is contingent upon the realisation of the Pontifical human, who knows how to check and balance selfish political power.

- Nasr considered the Promethean and the Pontifical man as opposites. The Pontifical man is modest and timid, while the Promethean is obsessed with materialism and worldly perfection. However, I must clarify that my depiction of Prometheus has not much to do with that of Nasr, which points to the arrogant pursuit of perfection through means of science and technology. Political Prometheanism, as I explain in Ancient Greek Democracy and American Republicanism, is anchored to a spirit of moderation; the fire Prometheus gifted to humanity, the fire of knowledge and moral judgment, does not promise endless improvement. Humans must be aware of their imperfect nature. Thus, they must not regard their ability to reason as a ticket to endless improvement. ↩︎

About the author

Dr Michail Theodosiadis is Lecturer of Politics at the University of Kurdistan Hewlêr in Erbil, Iraq. He is also a post-doctoral researcher at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, focusing on Ancient Greek, Byzantine and Middle Eastern political thought. Dr Theodosiadis has recently published a monograph with Edinburgh University Press under the title Ancient Greek Democracy and American Republicanism: Prometheus in Political Theory.