by Ruth M. McAdams

Tell us a bit about your book.

Temporality and Progress in Victorian Literature is about what happened when Victorians looked around for signs of the historical progress that was allegedly taking place on a broad scale. When they scoured their own lives and experiences, what they found instead was evidence that time was taking other shapes: regress, cyclicality, stasis, or rupture. The book looks at a wide variety of traces of a lingering past in Victorian literature – from unfashionable waistcoats to elderly people – and argues that they tend to trouble the view of time as progressive and continuous. These vestiges of the past reveal that progress is not just elusive but also surprisingly hard to theorize.

What inspired you to research this area?

Early in graduate school, I remember being confused by the truism that an ideology of progress was central to Victorian literature—I just couldn’t see it. I kept asking my mentors, reading long footnotes, and trying to figure out what I was missing. Eventually I dropped the question and wrote a dissertation about something else. When it was time to write a book, I initially intended revise my dissertation, but then started to become obsessed again with figuring out where progress was being theorized in the Victorian period. I kept being sent to texts that were understood to be theorizing progress but that weren’t really doing it.

Did your research take you to any unexpected places or unusual situations?

At one point, I got very deep in the weeds researching the history of men’s fashion to try to unpack all the shifting sartorial references in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair. Thackeray presents this vignette, for example, as a satire of Regency fashion from the perspective of the 1840s, and that’s how most scholars see it. But the image actually modernizes some elements of the fashion, especially the cut of the man’s trousers. So, the image actually doesn’t fully exploit the fashion differences between the 1810s and 1840s. This is not a topic on which I expected to develop expertise!

Has your research in this area changed the way you see the world today?

Politically, I’m a progressive, and I’m an American, so it has been painful to see right-wing authoritarianism gain popularity here and around the world. The celebration for the release of my book in November 2024 has been overshadowed by Trump’s re-election. One thing I’ve come to believe through my research is that generational turnover is not necessarily going to result in political progress. People on the left sometimes hope that we can just wait for demographic shift—toward a younger, more progressive cohort—to solve the world’s problems. Several of the Victorian texts I study take up this exact question and brilliantly expose its flawed assumptions.

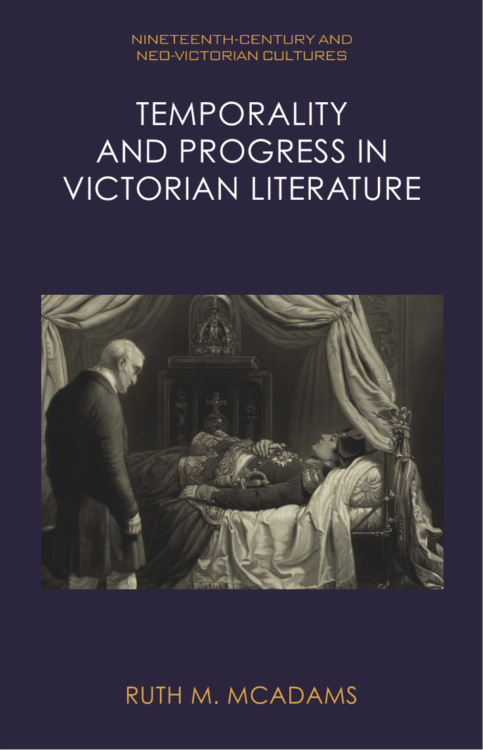

What is going on in your cover image exactly?

This image is a mezzotint taken from an 1854 painting by George Hayter that was destroyed by fire. It depicts an incident at Madame Tussaud’s, when the elderly Duke of Wellington (on the left) visited the wax effigy of a dying Napoleon, which is dressed in Napoleon’s real clothing, hat, and medals. The wax scene itself is highly romanticized representation of Napoleon’s death decades earlier, and a reminder of the centrality of clothing to envisioning the past. And then there’s the additional layer of Wellington’s visit shortly before his own death—the two never met in real life. So, the image struck me as evocative of the challenge of trying to register the passage of time.

What’s next for you?

In the years I was writing Temporality and Progress I was also helping organize a union for the non-tenure-track (contingent) faculty at Skidmore College. Toward the end of the revision process on the book, I realized that my interest in non-progressive temporalities had been shaped by my lived experience of cyclical precarity with regard to my employment. I have become increasingly interested in bringing together my identities as academic and activist. I wrote an article that connects the anti-union messaging of Charles Dickens’s Hard Times with the anti-union messaging of the Skidmore administration in response to our unionization campaign. And I’m planning a second book that will reexamine the Victorian industrial novel from an explicitly pro-union perspective.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the book

Argues that Victorian literature uses traces of a lingering past to theorize time as non-progressive and discontinuous

- Argues that the dominance of progressive history in the Victorian period has been overstated

- Considers Victorian literature in light of contemporary developments in philosophy of history

- Synthesizes critical conversations on liberal history, the temporalities of objects (in material culture studies and fashion theory), and the trajectories of the life (in Age Studies and queer temporality)

- Offers new readings of Benjamin Disraeli, William Makepeace Thackeray, Harriette Wilson, Harriet Martineau, Thomas Hardy, and Margaret Oliphant

About the author

Ruth M. McAdams is a Senior Teaching Professor in the English Department at Skidmore College. Her articles have appeared or are forthcoming in Victorian Studies, Victorian Literature and Culture, Nineteenth-Century Contexts, Nineteenth-Century Literature, and Pedagogy.