by A. J. Carruthers

Did Australia invent the idea of the avant-garde? It may sound like an absurd headline, but the non-European nature and origin of the avant-gardes is old news. As Jerome Rothenberg put it, the avant-gardes wormed their way into the heart of Europe from the East. Tom Sandqvist would go so far as to call Dada “Dada East.” This is because the first Dadaists came in from Eastern Europe, chiefly Romania.

In Literary History and Avant-Garde Poetics in the Antipodes: Languages of Invention I insist that the avant-gardes came to Europe from even farther out than the East. They came up from the South. I claim that, without the Antipodal avant-gardes, there would be no such thing as the avant-garde as we know it. The story of Australian avant-gardes is the story that begins well before avant-garde Europe, and continues long after. Antipodean influences are there before and after and yet also at key points in the historical and aesthetic development of the European avant-gardes.

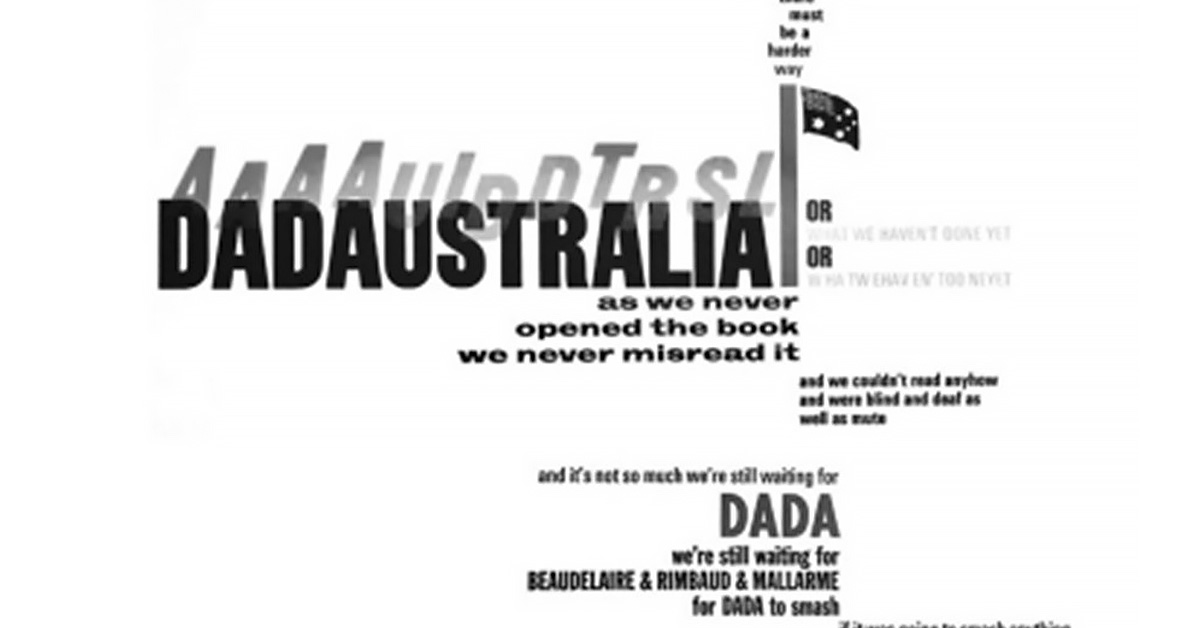

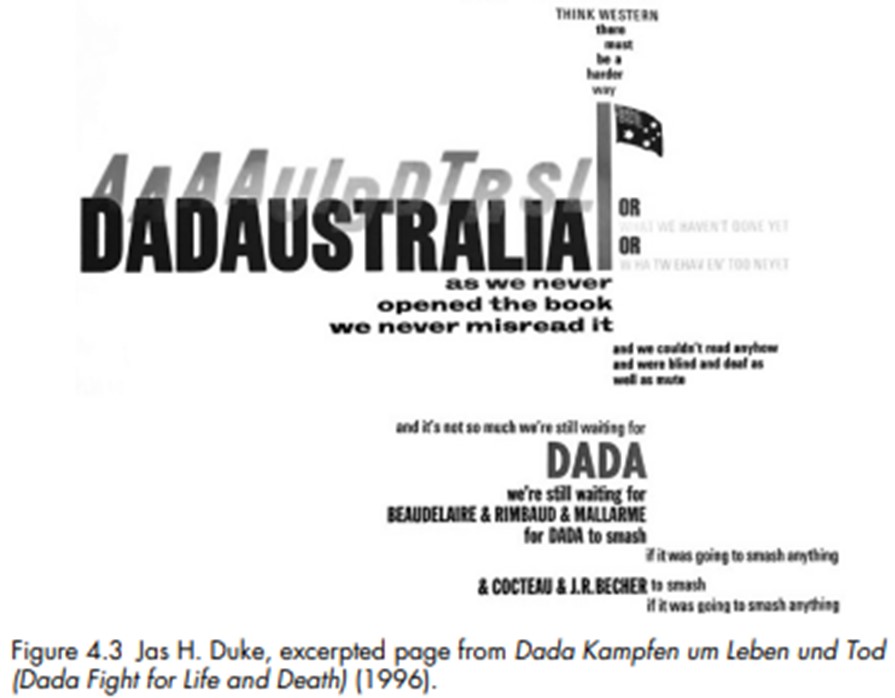

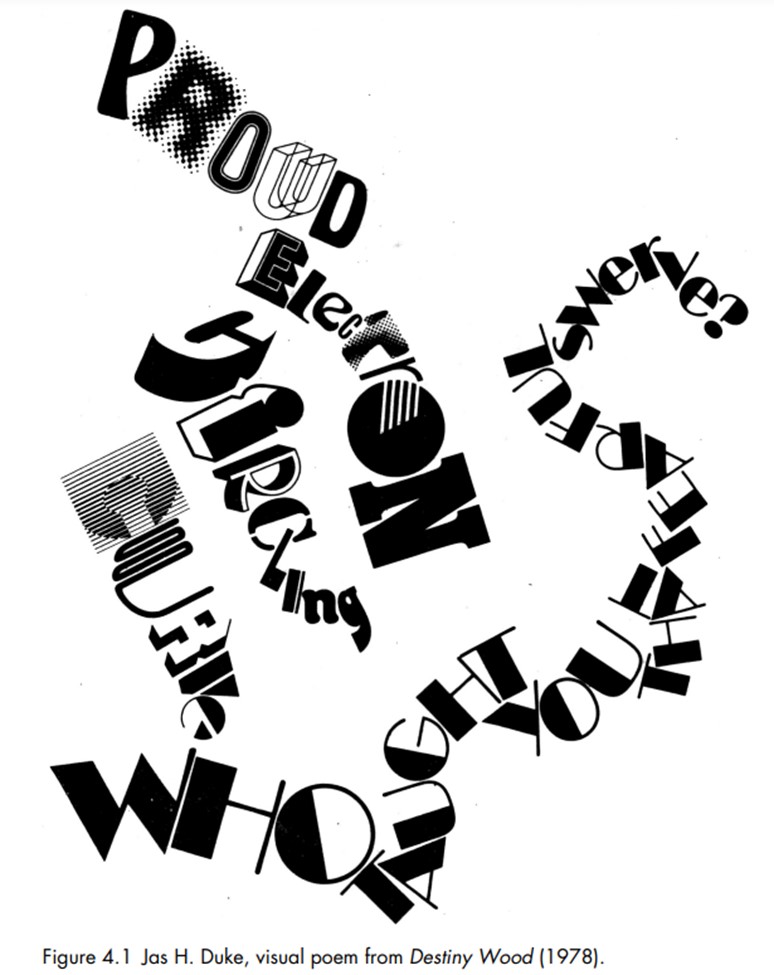

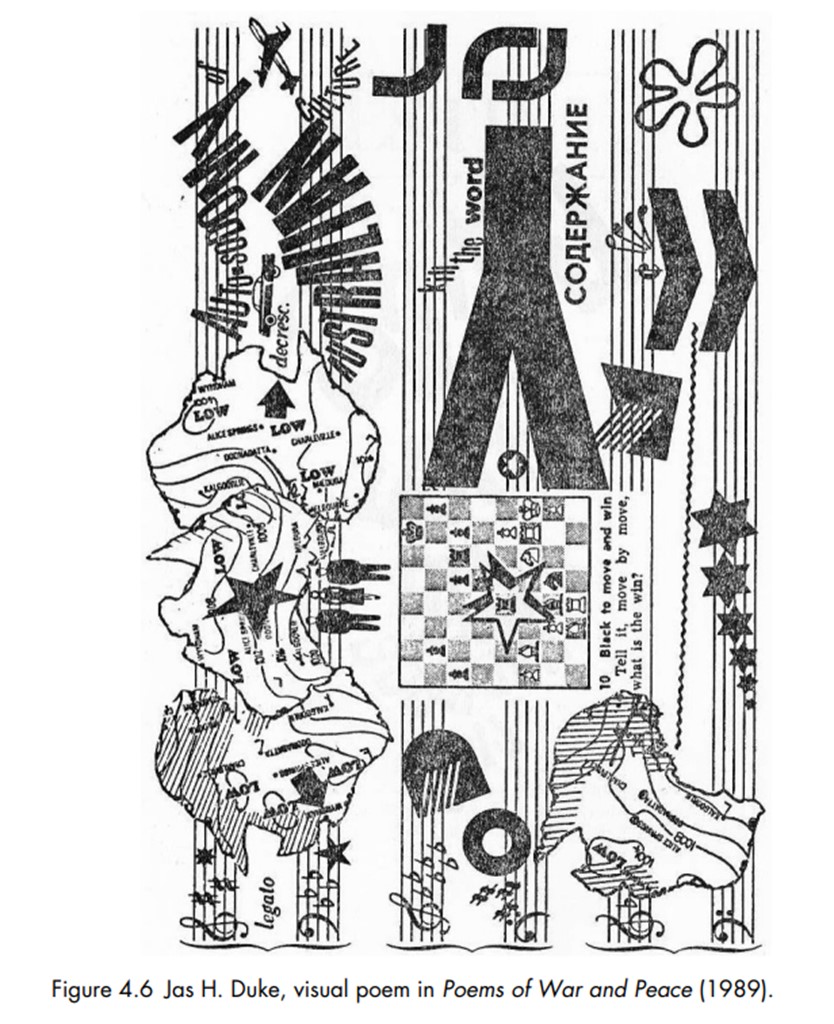

So goes, as above, the historical shorthand. Dada Ost leads to Dada Aust; “Dadaustralia,” then, is Jas H. Duke’s name for it, for the historical and national contradictions of Dada South (Duke was Australia’s first self-proclaimed Dada poet).

But like any literary history, I have had to lead with examples. Tristan Tzara’s performance of fragments of Arrernte and Luritja Songlines (Aboriginal epic cycles) at the Cabaret Voltaire in 1916 is one of the most well-known of them all. But others are just as curious. Christopher Brennan, Australia’s premier Symbolist and modernist poet, did his own version of Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés in the very same year that Mallarmé wrote it, 1897. Australians seemed to be hanging about in the shadows at the very inception of the twentieth-century revolution of the word.

Perhaps an even more curious evocation is in Jerome Rothenberg at the beginning of his anthology Technicians of the Sacred. It appears in the very first section, marked “Origins & Namings.” Rothenberg reproduces an Aboriginal Rain-chant, without permission, with lines that sound like “Dada.” Rothenberg is suggesting that the word “Dada” in fact has First Nations origins. Dada worms its way into Europe from the Southland.

There are, of course, problems with this. And the problem with this comes from First Nations avant-gardes themselves. There were and are “remote” avant-gardes under Occupation, as Jennifer Loureide Biddle put it, First Nations avant-garde artists and poets opposed to avant-Europe, and quite often opposed to the Western way of life. They would not foreclose the question of Antiquity. They didn’t hide their methods either. Lionel Fogarty is a towering figure in this regard. Under the conditions of Modernity, Antipodal avant-gardes from the 1940s to the 1970s in particular told their own histories that critiqued the piousness of avant-Europe and its churches, while enthusiastically responding to its poetics.

An Australian radical poet named Harry Hooton took exception to his age, writing avant-garde poetry in the shadow of the world-famous trickster Ern Malley. Hooton inspired Jas Duke, whose Dada ranks among the best ever produced. The eccentric stylist Ania Walwicz and her expansive avant-garde writings worm their way into the Antipodes from Poland. The cosmopolitan avant-garde poet Javant Biarujia invents a new language: Taneraic. Not only were they were inventive with language, they also invented new languages. They were not always Western, sometimes prophets, mostly revolutionaries, ignored by some, celebrated by others, often against the whole idea of Australia, and sometimes sad in their country. So it was with the longer history of avant-garde poets in Australia.

The missing avant-gardes of the Antipodes were hiding in the pocket of the avant-garde world-system all along. But why has the story of the world’s most durable avant-gardes taken so long to tell? It’s a confounding fact that the tale of the avant-gardes of Australia is one of the last to be told across all the continents and hemispheres of the globe.

Understanding Australia’s late entry into the avant-garde narrative requires grasping the problem of literary history. The international power of the avant-garde idea carries contradictions hitherto unexplored in global space. Literary history is still and perhaps always will be bounded by space, and materials. Literary movements like those comprising avant-gardes cannot be said to exist unless they have members and things, books and chapbooks, readings and recordings, adherents and detractors, local pundits and overseas supporters: in short, a real-world historical existence. “WE DO EXIST!” was the plea of a group of concrete poets from Melbourne in 1981.

My book provides examples, tables evidence. It closes the time gap. It presents these materials, many of them for the first time. It proclaims that an Antipodal avant-garde did exist.

Yet, and with some of these materials publically revealed, even that is not enough. Recuperation isn’t enough. It has been said of Revelation that it was not even enough for Moses to come down from Sinai and present the Tablets of the Law; the people had to accept the Revelation and adopt it into Law. It had to be completed on the side of reception. The Viennese psychoanalyst Theodor Reik spoke about this in his unusual 1959 book about Australia, Mystery on the Mountain: The Drama of the Sinai Revelation. The acceptance of the revelation of the Antipodal avant-gardes now lies with readers and enthusiasts within the field of avant-garde studies. More evidence awaits us, more drama and more mystery. I leave it to readers to decide the fate of avant-gardes in the Antipodes. It is my hope of course that this offering is accepted as a contribution to the internationalisation of our field and its expanded relevance. Australia invented the avant-garde, let that be the headline. But underneath it much more remains unknown.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the book

Examines Australian avant-garde poetry from the late nineteenth to the early twenty-first centuries

- Argues for Aboriginal and First Nations avant-gardes as a challenge to the Euro-U.S. constitution of avant-gardes in theory and history

- Proposes a re-definition of the meaning of national literature

- Explores the question of avant-garde literatures in settler-colonial and post-Soviet contexts

- A guide to unknown avant-garde texts, performances and prosodies from Concrete and Sound Poetry traditions

Literary History and Avant-Garde Poetics in the Antipodes maintains that this literary history poses a distinct challenge to the theories of the avant-gardes we have become accustomed to and changes our perspective of avant-garde time.

About the author

A. J. Carruthers is a poet, critic, author of Stave Sightings: Notational Experiments in North American Long Poems (2017), and three volumes of the long poem AXIS: AXIS Book 1 (2014), AXIS Book 2 (2019) and AXIS Z Book 3 (2023). Carruthers has worked in China, as Associate Professor in the English Department, Nanjing University, and is currently a Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University.