By Aubrey Westfall

The Scottish government has campaigned for a greater say over immigration ever since the Scottish Parliament was re-established in 1999. Scottish leaders argue that depopulation is the biggest economic and social threat to Scotland, and that more immigration to Scotland is necessary to compensate for an aging population. They claim that the current system, which has skills and salary requirements that apply equally to all areas of the UK, does not reflect the needs of Scottish employers or the cost of living in Scotland. To resolve the issue, the Scottish government proposed a Scottish visa that would tailor the current immigration policy to make it easier to attract migrants to Scotland.

For a moment earlier this year, it looked like a window of opportunity was opening for the Scottish visa: in the run up to the elections, the Labour leadership suggested that if they won (as was inevitable), they would be open to talks about the Scottish visa. The idea was quickly squashed once Labour took office: In October, a UK source told the BBC that the UK government is ‘not at all considering’ a separate visa for Scotland. This is hardly the first bait-and-switch suffered by the Scottish government – in the run up to Brexit in 2016, Michael Gove suggested that the UK government would give Scotland power to set its own immigration quotas through a points-based system once the UK left the EU. Nothing came of that promise, either.

Why has Westminster been definitively against considering a more flexible immigration system, regardless of which party leads the government? The unwillingness to consider a Scottish visa is fundamentally attributable to two sets of fears, neither of which are insurmountable.

The primary fear about a Scottish visa is that migrants would use it as a backdoor to enter the UK through Scotland. Record high net migration to the UK in the year 2023 gives weight to this concern. Anticipating this objection, the Scottish government proposed that separate tax codes north of the border would ensure that holders of the visa would have to live and work in Scotland. Opponents have suggested that such a system would be unfair and impractical, as it raises questions about differential rights north and south of the border. They ask, how would the policy navigate visas for those working in companies that operate in both England and Scotland? Would Scottish migrants and their dependents be entitled to UK citizenship after five years, after which point, residential restrictions could not be enforced? If Scottish migrants can only work legally in Scotland, what would prevent them from seeking alternative employment in the black economy south of the border?

The first two questions do not present a significant challenge – they can be explicitly addressed in policy. The concern about the black market speaks to systemic regulatory issues beyond the scope of immigration policy. Furthermore, devolved immigration policies have been implemented elsewhere, and they hint at likely outcomes for a Scottish visa. Canada and Australia, both of which also use a points-based system of immigration, have long featured regional differences in their immigration policies. Responsibility for immigration selection, much like what the Scottish government is proposing, has essentially been devolved to Quebec. Recent research in Canada finds that immigrants are much less likely to make an inter-provincial move than native-born Canadians. Earlier research finds 5-year rates of inter-provincial migration to be 2.8% for migrants and 3.5% for native-born Canadians, and one-year rates to be 0.8% for migrants and 1% for native-born Canadians. These statistics confirm the reality that once settled, most people stay put. The best way to make sure that migrants in Scotland stay, is to make sure that the employment, housing, and educational opportunities meet their needs.

The second concern of those who oppose the Scottish visa is the fear that granting Scotland power over immigration, power that is typically reserved to the central state, will embolden independence campaigners. Controlling immigration is about controlling borders, which is a central element of the modern state system. As Scotland is a country within the UK, wouldn’t allowing Scotland to control immigration therefore weaken the UK and give Scotland an attribute of a sovereign state? I don’t think so. The policy proposed by the Scottish government is essentially a tweak to the existing points-based system. Control over the policy would remain with Westminster. I have yet to see a convincing argument for why, given all of the other policies that have been devolved to Scotland, many of which support the administration of a Scottish visa, the visa would be the straw that breaks the camel’s back. And again, regional immigration policies in other countries have been implemented without fracturing the central political system.

Ultimately, all evidence suggests that the concerns over the Scottish visa are overblown.

About the Author

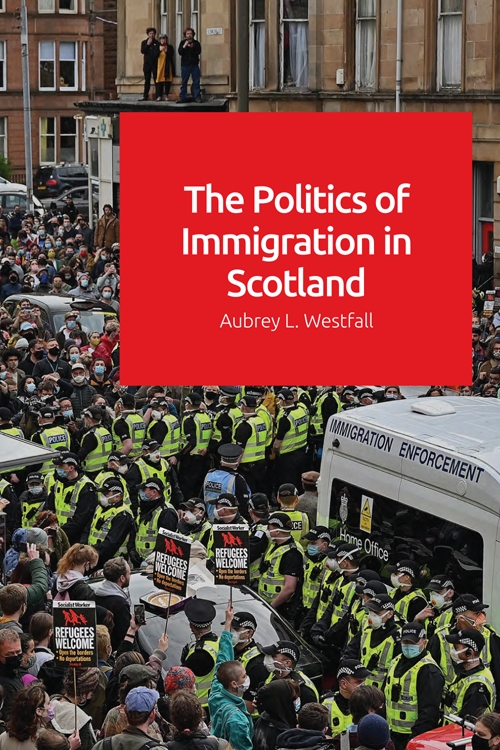

Aubrey L. Westfall is a Professor of Political Science at Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts. Her research explores the policies and sociopolitical practices regulating the political behavior of minoritized groups within Western democratic societies. She is the author of multiple articles and books, including The Politics of Immigration in Scotland (EUP 2022) and ‘Direct and Indirect Prejudice in Scotland’ (Scottish Affairs 33.2).

About the Book

The Politics of Immigration in Scotland examines immigration as a central strategy of Scottish nation building.

‘This welcome book is the first to provide a comprehensive analysis of the historical origins, political dynamics, party positioning and public attitudes on migration in Scotland.’ – Christina Boswell, University of Edinburgh

Explore related articles on the EUP Blog

A country built with diasporas and immigrants

Multiculturalism Isn’t a Dirty Word