by Cora Crampton

Frank O’Connor

Frank O’Connor (1903-1966) is considered to be one of the foremost translators of Irish language poetry into English. At the age of twenty-three he relocated from Cork city to Dublin, where he came under the influence of George Russell (‘Æ’), who introduced him to his old friend W. B. Yeats. Although there was a 38 year age gap between the two men, the brilliance of O’Connor’s work piqued Yeats’s interest. Yeats not only encouraged but also assisted O’Connor in his translation activities.

Collaboration and translation

Working with O’Connor facilitated Yeats’s proximate encounter with the Irish cultural tradition, exposing him to its beauty, vitality and at times strangely irreducible otherness. Yeats was also brought into contact with the eloquent and strident invocations of despair, satire and loss of the dispossessed Irish poets as they coped with cataclysmic socio-economic and political change following the Cromwellian and Williamite wars and plantations.

My article in the latest issue of the Irish University Review examines the translation of two poems composed by Aogán Ó Rathaille (c.1670-1726) and a third poem – the anonymously authored ‘Caoine Chille Chais’ (‘Kilcash’) composed c.1800. According to O’Connor, ‘Kilcash’ was one of Yeats’s favourite poems and there was ‘a good deal of his [Yeats’s] work in it.

Access to the original Irish poetry was only made possible because of the painstaking work of earlier scholars, and the contributions of the Irish Texts Society established in 1898, which published Irish material previously only available in manuscript form. Looking back and conducting a comparative analysis of these new translations with earlier English translations and the original Irish verse highlights the challenges encountered and the devices used to convey an equivalence of the imagery, structure and strangeness of the originals. O’Connor and Yeats found themselves addressing a linguistic tradition for which there were no English cognates. It was not possible to reproduce much of the subtle assonantal harmonies, compound words, internal rhymes and metaphorical otherness of Irish verse. Yet the new English poems managed to mediate much of ‘the kick’ and ‘excitement’ of the originals.

Yeats’s intervention in the translated poems was not insignificant; it is possible to trace echoes of the spare, direct, informal style-marks and syntactical flourishes of his late career in the new poems.

Source: Author’s photograph

Recuperating an ancient linguistic tradition

Ó Rathaille is regarded as one of the foremost elegists of the pre-colonial Irish tradition. His greatest achievement comprises the dozen or so personal lyrics in which he transcends the rigid conventions of his bardic profession, composed after he lost his lands in the late seventeenth century. Ó Rathaille became the victim of a new materialism, forced to wander amongst the ignorant and the boorish.

In late 1936, Yeats used his editorship of the Oxford Book of Modern Verse to help recuperate the dignity of the Irish literary tradition, which had been previously humiliated and suppressed. He emphasises his own affinity to this tradition and refers to the dispossessed poets as ‘symbols of our pride’.

Yeats arranged for Cuala Press, his sisters’ publishing company, to publish an anthology of O’Connor’s translated poetry, called The Wild Bird’s Nest in 1932, Lords and Commons in 1938 and The Lament for Art O’Leary in 1940 (planned before Yeats’s death in 1939).

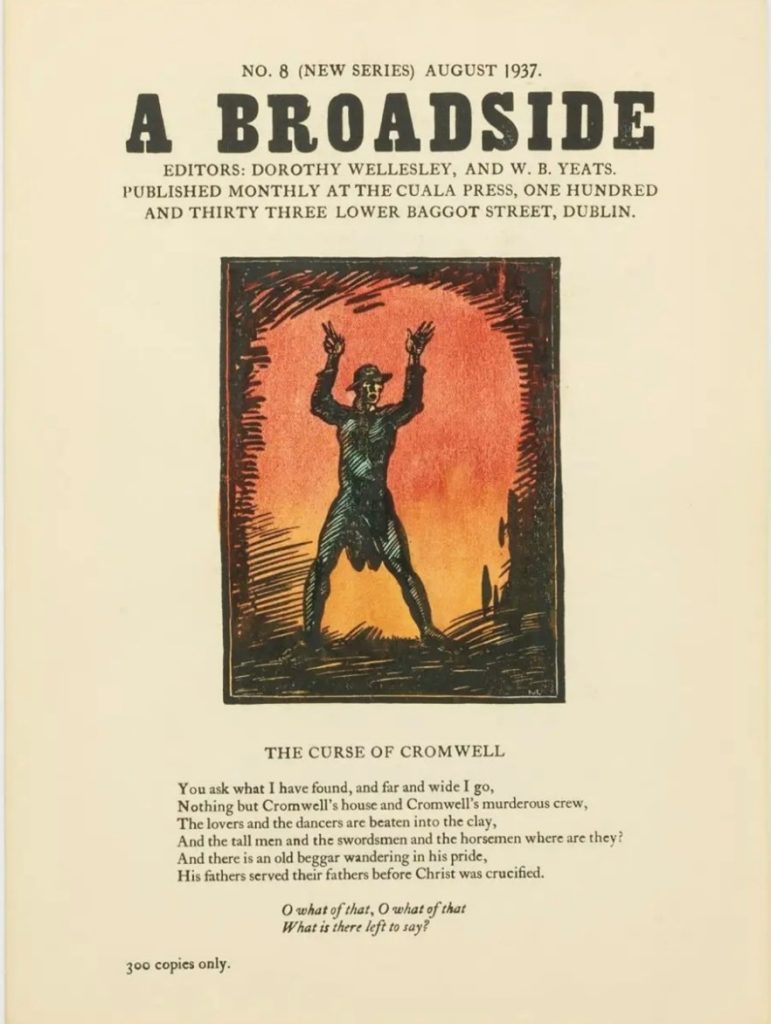

The Curse of Cromwell

The preoccupations of the dispossessed Irish poets resonated with Yeats’s own contemporary anxieties in what he saw as the socially and politically topsy-turvy world of the 1930s. He felt compelled to respond to the character of his times by employing ‘the only vehicle I possess – verse’. ‘The Curse of Cromwell’ (1937) is a poem concerned with questions about society, audience and the future of poetry and was the means through which Yeats vented his concerns.

Sophisticated thought and emotion combine with strong thematic and stylistic echoes of Ó Rathaille and other Irish poems in this complex literary ballad. The ruination of an idealised tradition is captured in the poem’s Kilcash-like setting and atmosphere. Yeats ventriloquises the Irish poets as he expresses his own contemporary concerns that an elite, refined way of life is disappearing. In July 1937 he admits, during a BBC radio broadcast, to appropriating the last line of one of the Ó Rathaille poems for ‘The Curse of Cromwell’. It was a line he was very fond of repeating:

‘There is an old beggar wandering in his pride/His fathers served their fathers before Christ was crucified.’

Source: Cover of Broadside no. 8 series 1937.

Read Cora Crampton’s latest article in Irish University Review

About the journal

The Irish University Review, founded in 1970 at University College Dublin, is a peer-reviewed journal that publishes essays on Irish literature and culture:

- Editor: Dr. Emilie Pine

- Affiliation: Affiliated with the International Association for the Study of Irish Literatures (IASIL)

- Publication: Two issues per year

Sign up for TOC alerts, subscribe to the Irish University Review, recommend to your library, and learn how to submit an article.

About the author

Cora Crampton was awarded an MA in English literature from NUIM Maynooth in 2022, the research for which forms the core of her article in the November-December 2024 edition of Irish University Review. Cora is the recipient of the Chiefs and Clans Prize 2024 for her research on political marriage in sixteenth century Ireland.

An excerpt from her work on the representation of the Wyse Powers in Ulysses was broadcast on RTE Radio for the 100th anniversary of the publication of James Joyce’s masterpiece. Cora was awarded a place on the Irish Writers Centre National Mentoring Programme in 2024. She is the current holder of the Lord Walter FitzGerald award for original historical research pertaining to County Kildare and its environs.