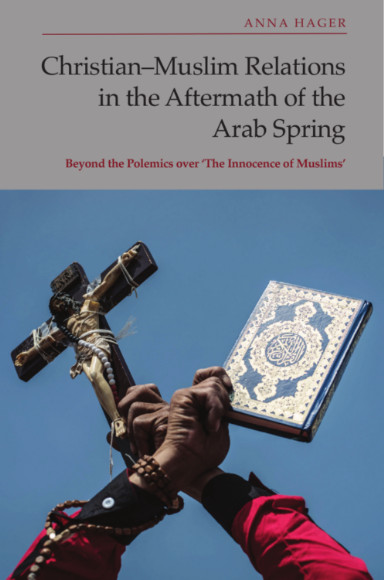

By Anna Hager

The phrase, ‘Christian-Muslim relations in the Middle East’, may too easily call to mind associations of violence. Isn’t there more to telling this history than a story of violence and submission?

In recent decades, Christians in the Middle East have made headlines as the targets of violence. From Egypt to Iraq, including the civil war in Syria and the plight of Palestinian Christians, Christian life seems to be in great danger. And yet, relations between Christians and Muslims cannot be reduced to a mere account of violence and submission to Islam.

My book, Christian-Muslim Relations in the Aftermath of the Arab Spring, uses a controversy over an ‘offensive’ video as a starting point for exploring Christian–Muslim relations in Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan.

A tale of contradictions

Relations between Christians and Muslims are very complex; they are both positive and negative, encompassing both tension and cooperation, respect and suspicion, a search for proximity and an avoidance of the other. The ability of Christians to pressure Muslims is weak in some scenarios, and surprisingly strong in others. Islamists and Salafis are both powerful, and quite fearful for their reputation.

Islamists like Christians

Islamists and Salafis hold contradicting positions towards Christians in the Middle East but, in order to protect their reputation, they like to outwardly demonstrate friendship towards Christians. It increases their standing on the political landscape. The late leader of Hezbollah, Hasan Nasrallah, for instance, was quite good at this show of proximity to Christians. He spoke a lot about Christian-Muslim unity in Lebanon against Israel and had many connections among Christians. His behaviour was repeated by other Salafis in Lebanon. In Egypt, the organisation al-Gamaa al-Islamiyya used to be a violent organisation, targeting Copts in the 1970s in Upper Egypt. However, during the Arab Spring they suddenly turned into moderate actors and established connections with priests and Coptic activists.

Rituals

Let’s face it, rituals can be quite boring. But you probably didn’t know that they can also be quite powerful tools to exert pressure. For instance, if Christians attend iftar, they expect Muslims to at least wish them a ‘Merry Christmas’, if not attend Christmas service. And if Muslims do this then they acknowledge, to an extent, that Christian feasts are as valid as Islamic ones.

Who needs human rights?

Surprisingly, when Christians demand an improvement of their situation in society, many of them do not use the language of human rights. These are considered a western import. Christians do want more rights, but they demand these by appealing to a long history of Christian-Muslim coexistence, a shared language, values and culture. You can also hear a lot of Middle Eastern Christians speaking of Islam as a religion of peace and tolerance. This does not mean submission to Islam. Instead it means that Christians expect Muslims to submit to the ideal of Islam as a peaceful and tolerant religion.

Warning against potential violence is useful

Yes, the prospect of violence can be quite useful. Warning fellow Christians and Muslims about the potentially huge damage of violence helps to unite them against a shared enemy.

Sign up to our mailing list to stay up to date with our free content and latest releases

About the author

Anna Hager is currently a research fellow at the University of Vienna, Austria. She has published on Christian-Muslim relations, Christians in the Middle East and the Syriac Orthodox Church in Guatemala.

About the book

Christian-Muslim Relations in the Aftermath of the Arab Spring uses ‘The Innocence of Muslims’ controversy as a starting point for exploring Christian–Muslim relations in Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan. Instead of dismissing the resulting condemnations and joint reactions as shallow and ritualised displays of solidarity, Anna Hager argues that they offer insights into the mechanisms of Christian–Muslim relations.

Find out more about Christian-Muslim Relations in the Aftermath of the Arab Spring