By Francesco Marchesi

The end of the neoliberal belle époque

The events of the first twenty years alone of the twenty-first century have put an end to the philosophical twentieth century. From the 2008 financial crisis to the shock of the pandemic, the transformations that took place during this period have made the philosophical demands that animated the previous century, particularly its final portion, obsolete. The deconstruction of all absolutes promoted by Heidegger and Wittgenstein, as well as their parcelling into the flow of differences by Deleuze and Foucault, now appear as residues of an era that dedicated most of its energy to the critique of every order of experience, history, and even politics.

This era terminated with the end of the privileged terrain that these theories found in the final thirty years of the century, the neoliberal belle époque, which exalted the rejection of order, the conception of freedom as individual difference, and the suspicion of every form of structuring. And to this, we should of course add their necessary correlate: the equivalence of all absolutes (from systems of thought, to economic regulation, to state sovereignty), understood as sources of totalitarian repression and closure.

A new philosophical situation

The periodic economic, political, environmental, and health crises which have returned to pass through the industrialised West have, on the contrary, emphasised the importance of structuring, regulation, and order. Indeed, if economic depressions have returned to show the despotism that the deregulated market exercises on our lives and the need to collectively control it, the pandemic event represented a sort of global comparison of the different forms of governance. Those that were more regulated, and had greater availability of public goods, reacted promptly and with better results, while those that were more destructured and privatised reacted with difficulty and paid a much higher price.

These episodes and trends call philosophy into question in two main ways. On the one hand, they speak to the need for structuring, and on the other, they speak to the difference between various forms of order, which are traversed by divergent interests and perspectives. In short, now is no longer the time to consider how repressive a collective structure might be for our individuality, but instead how much it could defend us from the risks and uncertainties of the market, and how the power relations within each order determine its orientation in favour of one social part or another.

Machiavelli: The political productivity of conflict

Niccolò Machiavelli is the first in our tradition to think about the productivity of political conflict – its capacity, on the model of ancient Rome, to construct new orders, institutions and forms of life.

Machiavellian conflict is not opposed to structuring as duality or multiplicity, but instead mediates between the absolute plurality of individuals and social groups and the unity of order as such. Machiavelli, by re-elaborating the mixed Roman order and the conflict between its institutions, especially the senate on the aristocratic side and the tribunate on the plebeian side, suggests the elaboration of a mixed, or triadic, ontology. Here conflict is the intermediate element between one and many that overcomes the aporias of binary structures noted above. Conflict organises plurality within institutions on the one hand, while on the other it is precisely the prevalence of this conflict between institutions which decides the overall character of order. In short, it decides whether it is in favour of one part or the other.

Mixed ontology

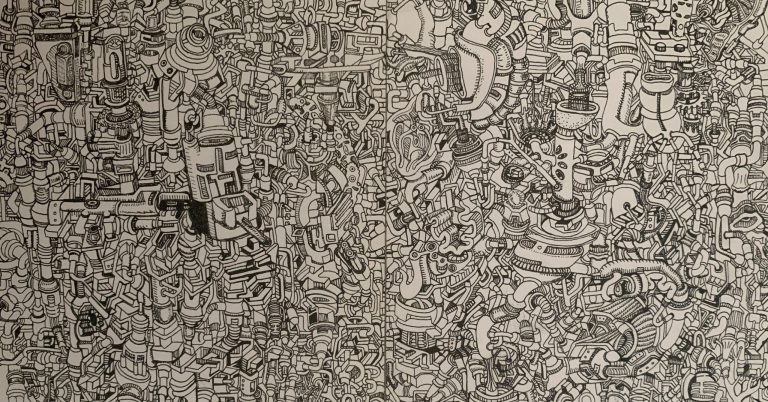

An ontology with Machiavellian characteristics therefore grasps conflict first of all as an instrument of organisation for plurality and as degree zero of mediation: no longer flat repetition or irrational nucleus within order, conflict articulates multiplicity by tracing a line of demarcation with the adversary – here, to separate means to organise the parts, and to do it at a sort of degree zero, through a simple division into parts, without the qualitative leap of rationalist or dialectical mediations. The organisation of plurality is only the first step in an overall instituting procedure, which is made up of this first step and a second one constituted by the conflict between institutions and for hegemony over order.

From this procedure, a geometry of conflict derives, that is, a non-neutral concept of structuring that is traversed by a struggle between parts for prevalence within it. This struggle is not only a means for the generation of order, but also an instrument for measuring its specific quality: the geometry of each structure, its distinctive sign, its form, in fact derives here from the state of the relations of force between the organised parts that compose it. In short, only relation between conflictual parts allows for difference and historicity to be saved, as a coexistence in a whole and through the recombination of their articulation. Neither monistic, nor dualistic, nor pluralistic, a Machiavellian ontology has a mixed or triadic structure. It can allow, at least in part, for thinking the two needs which traverse the new philosophical situation: the modalities of structuring and the conflictual orientation of this same ordering act.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all our free content and latest releases

About the book

Machiavellian Ontology studies the philosophical implications of contemporary theories of conflict and proposes a new political ontology.

Francesco Marchesi offers an original reading of Machiavellian thought as well as a critique of some of the most influential contemporary theories of conflict including Foucault, Schmitt, Arendt, Lacan and Althusser. In doing so, he proposes an innovative, conflictual political ontology that, with Machiavelli, is capable of conceiving the affirmative, and not only deconstructive, power of conflict.

About the author

Francesco Marchesi teaches History of Political Philosophy at the University of Pisa. His main research areas are Renaissance and contemporary political thought. His books are: Ritorno ai princìpi (Carocci, 2022), Geometria del conflitto (Quodlibet, 2020), Cartografia politica (Olshki, 2018), Riscontro. Pratica politica e congiuntura storica in Niccolò Machiavelli (Quodlibet, 2017).