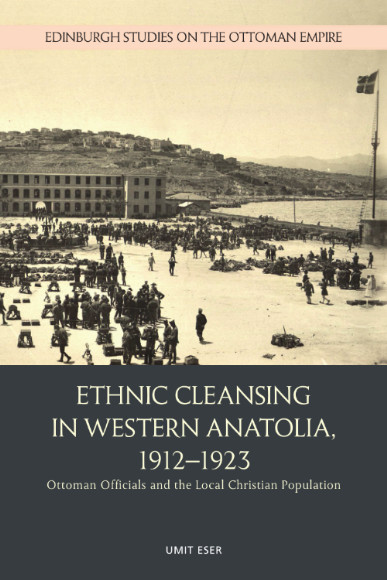

By Umit Eser

From the deck of HMS Iron Duke at midnight of 13-14 September 1922, Osmond Brock, Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, witnessed Smyrna, the major Ottoman port city, blazing furiously. Large swarms of people could be seen on the quay as the fire had not yet reached the waterfront. At about 2.00 a.m., a large cinema on the front caught fire, and from that time onwards events moved rapidly. As more houses along the front burst into flames, the cries and shrieks of the crowd could be heard plainly above the noise of the fire. Some of the bystanders saw a grim humour in the sign over the arched door of the cinema in black letters two feet high. It was the name of the most recent film shown: ‘Le Tango de la Mort’.

The violence in the transition from Ottoman Empire to nation-state, which constituted the prehistory of Turkey’s Republican era, determined potential migration patterns and alienated Ottoman elites as well as non-Muslim communities before reducing them to minorities. Organized violence and intimidation at the end of the Ottoman Empire have been the subjects of competing historiographies and have therefore acquired different significations, so much so that they are still at the core of heated debates. In order to understand the current exclusionist trajectory and authoritarianism in the post-Ottoman geographies, particularly Turkey, the modern origins of intolerance, organised violence, forced migration, and ethnic cleansings in the first quarter of the twentieth century must be investigated.

After the traumatic repercussions of the defeat in Tripolitania in 1912 and the Balkans in 1913, Ottoman Christians who had lived in Anatolia for centuries were stigmatized by the Committee of Union and Progress as the ‘enemy within’, or the ‘cancer in the state’ posing an intolerable risk to the Empire’s internal security. During the Greco-Turkish War in 1919-1922, all Orthodox Christians were assumed to be supporters of the Greek nationalist agenda unless they proved otherwise. Nonetheless, the Muslim–Christian coexistence in Western Anatolia continued until September 1922, thanks in part to the efforts of the Greek High Commission under Aristides Stergiades and its policy of co-opting high-ranking Muslim provincial officials who had previously served the Ottoman government. These Ottoman officials, along with Stergiades, the high commissioner in the occupied zone, represented the last chance to preserve the coexistence of different ethno-religious communities in the region.

About the book

Ethnic Cleansing in Western Anatolia, 1912–1923 aims to break new ground by tracing the careers of the Ottoman bureaucrats under the rule of the High Commission, who provided continuity between different time periods. Although many of these people were later characterized by Turkish nationalist historians as ‘traitors,’ this study reveals the ways in which they protected various local ethnic groups from persecution and other more mundane forms of discontinuity. In the ‘moral grey line of in-betweenness,’ these were people who were compelled to make choices for the sake of survival.

The book addresses a series of questions in order to analyse the intertwined dialectic of collaboration and resistance: to what extent are these bureaucrats’ acts seen as collaboration with the Greek forces? Was there a regional demand for stability and power-sharing, or a kind of personal hatred directed at the former nationalist cadres centred in Ankara? Did the Ottoman bureaucrats’ alignment with Greek authorities arise from the constraints of Ottoman authorities in Constantinople, or the desires of these civil servants to be a part of the new governance mechanism? Did these people plan to benefit from the Greek occupation, which would pave the way for the redistribution of wealth in the region? Did they have a secret agenda for the restoration of Ottoman rule in the region through feeding the inhabitants’ hostility towards the Greek administration and attempting to exploit their posts to mislead the Greeks?

If not, did the inclusionary policies of the Greek administration play a role in the formation of the ‘collaborationist’ policies? Did its fluid and ambivalent character offer the chance for dissidents of the nationalists in Ankara? In trying to find answers to these questions, this timely research exhibits that even the most contested of national conflicts exhibit a remarkable capacity for coexistence at the local level, a capacity that is all too easily forgotten amid global conflicts today.

Even outside of the archives, ordinary sepia-coloured postcards and photographs reflecting almost every corner of the Ottoman geography before 1922 show how Ottoman Christian communities left their mark on the cities from which they were expelled. Schools, hospitals, places of worship or celebrations – these postcards bring to mind the pain and grief for a land lost forever as much as the collapse of a cosmopolitan empire. As a historian, one of my goals is to study and make sense of the often sorrowful experiences of unwelcome figures of the past. This book serves that goal.

Save 30% on your copy with code NEW30

About the author

Umit Eser is Associate Professor of History at Necmettin Erbakan University and former Visiting Researcher at Centre d’études turques, ottomanes, balkaniques et centrasiatiques (CETOBaC). His articles addressing ethno-religious pluralism in late Ottoman cities, political violence in the late Ottoman period, and lost homelands in narratives after the Asia Minor Catastrophe have been published by British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Journal of Modern Greek Studies, and Diyâr: Zeitschrift für Osmanistik, Türkei- und Nahostforschung.