By Phillip Cole

The sight of the IOC Refugee Team drifting down the Seine in a boat during the opening ceremony of the Paris Olympic Games was a moving moment – the idea of the refugee is powerful and emotive, as well as being embodied within international law in the 1951 Refugee Convention.

The television commentator noted that there are an estimated 120 million forcibly displaced people in the world. However, this does not mean there are 120 million refugees. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that by May 2024 there were 43.4 million people who meet the definition of refugee.

The rest of the 120 million fall outside of that definition and so outside of international protection, and possibly outside of people’s political awareness.

In a sense, refugees have a place within the political order of things despite their displacement. They have an official legal status with rights attached to it and, ideally although not that often in practice, have an entitlement to sanctuary in a safe place. There is also an increased focus on the importance of the refugee voice in policy-making bodies such as UNHCR and the Global Refugee Forum.

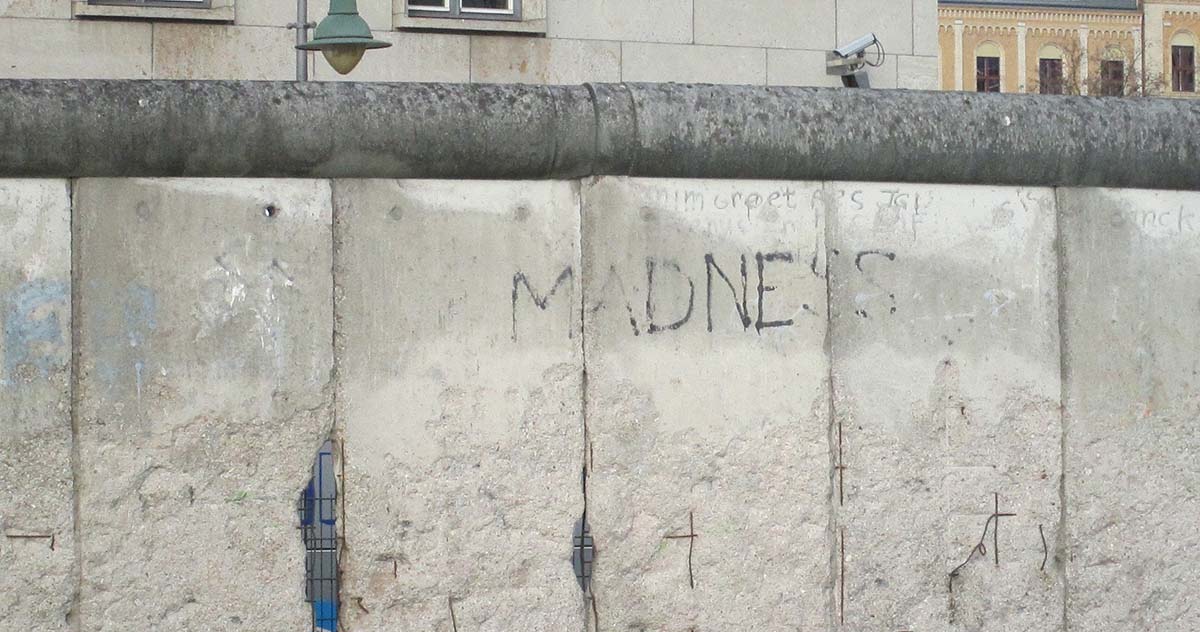

But all those other displaced people have not only lost their place in the political order, they are also radically outside of that order, with no official status, no special rights or protections, and no voice or agency when it comes to policy forums that discuss what should happen to them.

Who is left outside?

So who are these others? The vast majority of them (68.3 million) are internally displaced and the rest are asylum seekers, people who have not yet received the status of refugee.

And yet this still does not tell the whole story because UNHCR only counts those people who are displaced by some form of conflict, such as persecution and war, and this omits two major causes of displacement: climate-related events and development projects.

In their 2024 report, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre estimate the total of internally displaced people to be nearly 76 million by the end of 2023, with the majority of the new displacements that year caused by disasters rather than conflict. Around 20 million people are displaced by disasters every year.

Development projects – including events like the Olympic Games – are a major cause of forced displacement, estimated at around 10 to 15 million people every year. If we include displacements like these, and also slow-onset climate events as well as disasters, and also consider the impact of severe economic deprivation causing people to move, then the number of forcibly displaced people in the world becomes difficult to estimate but far bigger than the 120 million cited by UNHCR.

What should protection mean?

Do we need to widen the concept of the refugee to bring all these displaced people within the legal protections offered by the 1951 Refugee Convention? My view is that we do not. The Convention does a specific job for a specific issue, and many of the protections it offers are not actually relevant to these other kinds of displacement.

At the same time, though, it cannot be right that millions of people impacted by displacement should fall outside the scope of any kind of political protection, leaving them dependent on humanitarian aid.

This humanitarian/political distinction is important. Humanitarian responses to displacement are typically temporary forms of basic food and shelter, while political solutions are more permanent, seeking to restore full membership of political communities.

The former has been seen as the appropriate response to disaster displacement, for example, despite the fact that such displacements can last for decades or more. And people displaced by development projects, such as dams, are permanently displaced, with their homes completely obliterated, very often driven out through extreme violence.

The impact of displacements of this kind on people’s lives in terms of their duration, the trauma of exile, and the exclusion of the displaced from their communities, mean they are profoundly political, calling for permanent political solutions and protections rather than temporary humanitarian care or ‘guiding principles’.

This is not to argue that we need a one-size-fits-all form of protection when it comes to forced displacement. Rather, we need to politicize all forms of displacement and search for permanent political solutions and protections which restore people’s memberships of their communities, rather than force millions of people to live their lives in ‘temporary’ exile from the global order.

Crucially, all displaced people should be stakeholders and participants in forums and processes which decide policies that seek to address forced displacement. The globally displaced share the same experiences, traumas and isolation, such that who gets to speak about displacement becomes the key challenge for everyone concerned.

In the end, justice for the displaced may not come from governments or international organisations, but from solidarity and activism with and through and by the displaced themselves.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the author

Professor Phillip Cole teaches Politics and International Relations at the University of the West of England, Bristol. He is also author of Philosophies of Exclusion: Liberal Political Theory and Immigration (Edinburgh University Press, 2000), and The Myth of Evil (Edinburgh University Press, 2006). He is co-author of Debating the Ethics of Immigration with Christopher Heath Wellman (Oxford University Press, 2011).

About the book

Global Displacement in the Twenty-First Century builds an ethical framework for responding to the urgent crisis of global displacement.

Phillip Cole calls for a radical review of what international protection looks like and who is entitled to it, bringing together different issues of forced displacement in one place to provide a systematic overview. Cole places the experiences of displaced people at the centre, and argues that they should be key political agents in determining policy in this area.

Now available in paperback! Get 30% off your copy with the code PAPER30.

Find out more about Global Displacement in the Twenty-First Century.