By Fatima Mojaddedi

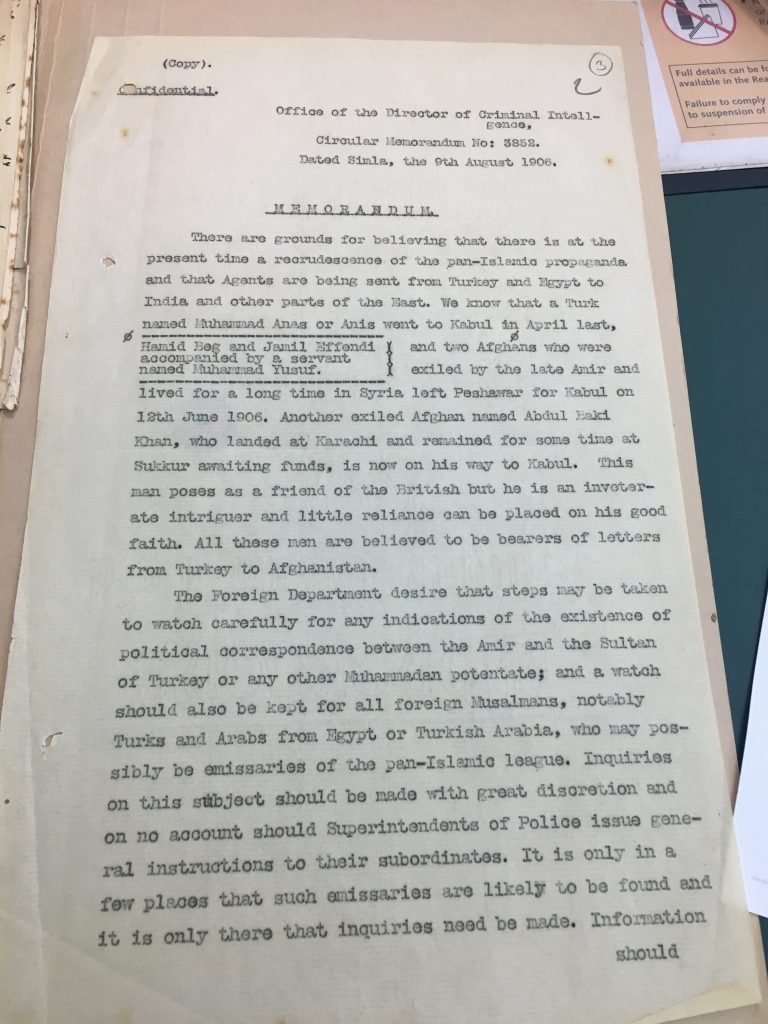

The telegraphic wire, transatlantic, under the sea and linear, but never controllable, became a metaphor for cultural difference and political disturbance precisely because it enabled global connectivity in the imperial frontier. In this sense, communication technology generates its own kind of fear and fantasy. The desire for unmitigated global reach and contact quickly transformed into a British and European obsession with the specter of uncontrolled signifiers: of discourse, news, rumor, and information that were now at large in places like Afghanistan.

Like any emerging technology lacking a clear cultural expression, the telegraph was new as both a material invention and an object of desire. Its power of dissemination was unstoppable. And, as early as the 1920s, when cable telegraphy was first introduced to the Afghan government, this power faced threats from the resurgence of repressed forces including—at that time —the specters of Bolshevism and Pan-Islamism.

A shot across the bow

In 1923, when land-line telegraphic communication between London and Kabul was first inaugurated, a small diplomatic row erupted over who should send the first, and presumably congratulatory, message. Amir Amanullah and King George V each awaited a note of goodwill and friendship from the other. This courtly moment of anticipation during the inter-war period—when British, Soviet, and German governments were competing over influence in Afghanistan and the broader region – revealed confusion over which country benefitted the most from the telegraphic connection. Was it the purveyor, who would also presumably control access and communication channels, or the recipient, a developing country in the so-called “third world” eager to be in contact with the international community?

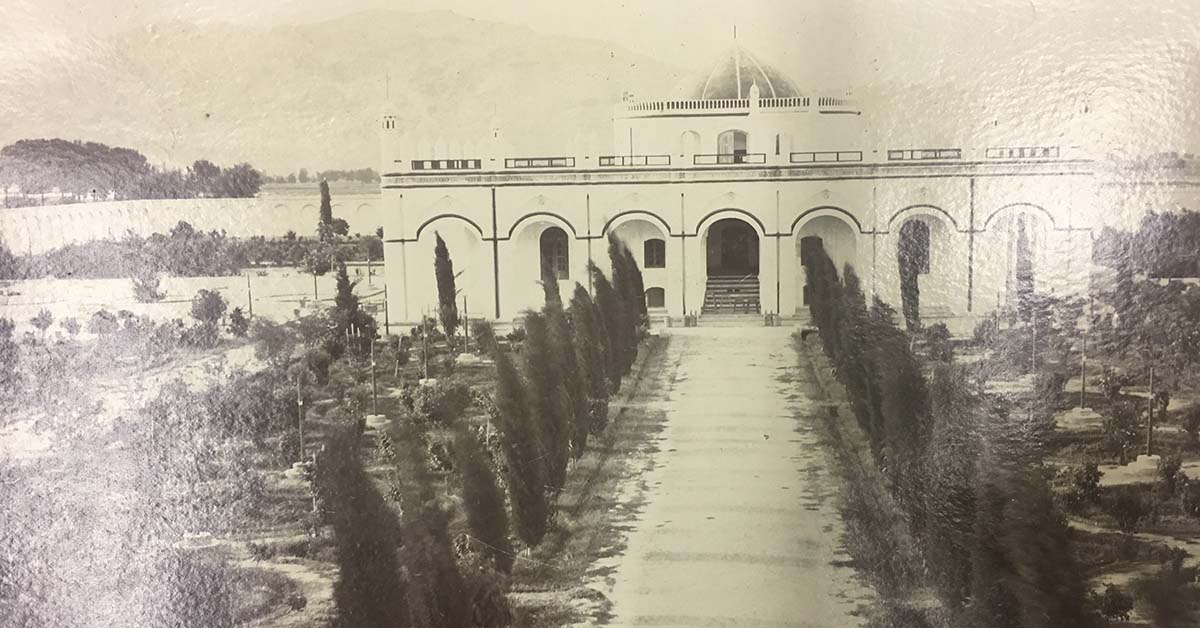

In the end, Amir Amanullah sent the first telegram, commencing decades of long-distance communication mediated by the latticed towers of telegraph stations in Kabul, Delhi, and London. It was a shot fired across the mediatic bow, and he used it to clear a new place for himself in a modern world of political crisis.

‘On the occasion of the inauguration of telegraphic communication between Afghanistan and Great Britain I have the honour to express my sincere gratitude to your imperial majesty for the facilities rendered by the officials of your majesty’s government in the progress of the work. I hope the installation of this telegraphic communication will be the key to good relations between Afghanistan and Great Britain. I do hope that the British imperial government would in view of her obligations toward humanity and civilization consider the miseries and misfortunes of the Muslims as a matter of great importance in order that the friendly relations which existed for a long time between Great Britain and the whole Muslim world might be re-established. Amanullah, Amir of Afghanistan.‘

A bold and impassioned politics of Afghan nationalism and Pan-Islamic solidarity travelled through the wire and across regions. It is as if the unexplored link between cities and continents hitherto separated by a lack of infrastructure and technology had a grip on the Amir’s imagination, allowing him to take heart in the telegraph and turning the transmissions into a declaration of political solidarity with the Muslim world.

These uncertain exchanges and the difference in how telegraphic technology was received reveals a contemporary fixation with something that could not be readily expressed but impinged on collective consciousness nonetheless: how to be in the modern world of mediation with others?

Imperial centers and peripheries

For Afghans, the telegraph was a revolution in communication, but as a token of the modern era it was envisioned differently. The idea behind the sharing of telegraphic technology was that Afghanistan and Great Britain, estranged by military violence, would become closer through the messages of government officials passing between them like homing pigeons from a bygone era. Kabul would become a center within the imperial ‘periphery’ long associated with cultural violence and excess, and this integration into the global community was also expected to provide colonial interests with a more secure and accessible foothold.

The unfurling of a new map of inclusion and connectivity was part of an emerging material culture and enchanted world of contemporaneous belonging. I think this newness is inseparable from what Amir Amanullah’s telegram signifies: an open horizon marked on one hand by a culture of cosmopolitan access and on the other by political upheaval and colonial expansion, such that access to others was also a condition of possibility for violence to come. The journalist and intellectual Mahmūd Tarzī captured it best when he predicted that enhanced integration with the West would cause a conflagration of ‘fire and smoke.’

Anxieties and ambivalences

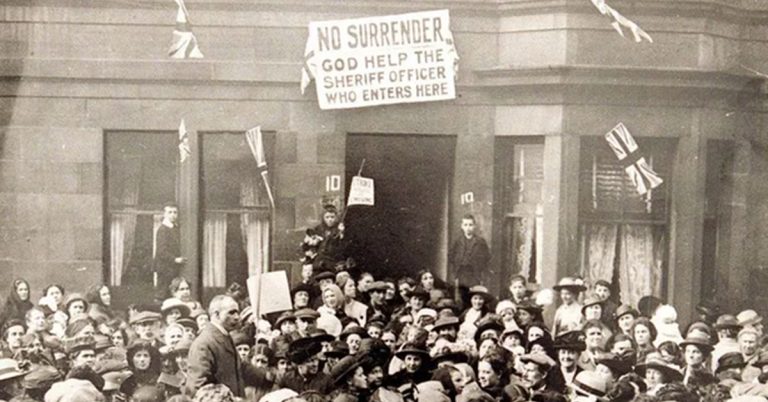

Thus, at the heart of the tension over media technology and connectivity was a deeper ambivalence about the place of ideological and cultural difference in the modern era of technology, and a concomitant nervousness about the task of interpreting that difference. It is undeniable that the telegraph made something bold possible but this opening of thought, communication, and political action was already inscribed in a culture of imperial anxiety over the emergence of political Islam.

In this context, the eagerness of the Afghan government to embrace ever newer technologies became a renewed source of European and British paranoia. It is possible to see this tension as a symptom of modern media’s porosity and capacity to re-organize social and political relations along the lines of those who own and are adept at its uses, and those who acquire these technologies as a gesture of political goodwill or through patronage networks. But I see this as an abstract and more intriguing story about the place of media and collective discourse in the global political scene, where the journey of cosmopolitanism began in earnest with the possibility of global address.

The place of these media in modern Afghanistan shows us that the possibility of address brings an excitement over global contact and thus the possibility of political and ideological exchange beyond the occidental frame of Europe and the West. The idea that emerges from the tension of being, addressing and communicating in a modern way is that modern experience is also linguistic. Like other symbolic activity, it is never complete or entirely understood so much as it is part of the psychic question of how to be with others and other others. It is best to view the role of media in Afghan society not as a transformation, but as an act of ongoing translation. It is constantly changing and fragmentary, an emerging space which absorbs cultural and subjective anxieties that transcend either the excitement of the new or an outright fear of global permeability in the era of upheaval.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the author

Fatima Mojaddedi is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at UC Davis. Her research interests include Afghan culture, archival histories, and politics; critical and literary theory, psychoanalysis, questions of subjectivity, cultural memory and violence, language, aesthetics, modernity, and post-modernity.

About the journal

Afghanistan is the journal of The American Institute of Afghanistan Studies, dedicated to the cross-cultural study of Afghanistan and its surrounding regions, delving into its rich history from a wide variety of humanities-focused angles.

Following a successful Subscribe to Open campaign, it flipped its 2024 volume to Open Access!

Sign up for TOC alerts, subscribe to Afghanistan, recommend to your library, and learn how to submit an article.