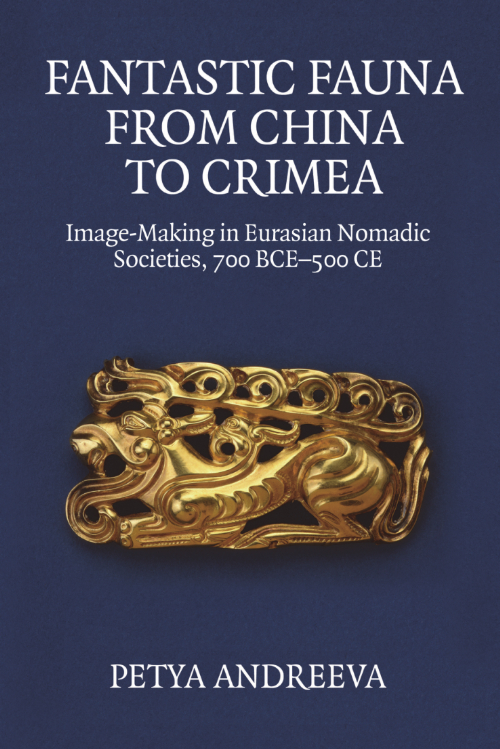

by Petya Andreeva

Tell us about your book.

My book explores the visual and material cultures of the ancient pastoral societies that lived and moved across the 5000-mile Eurasian steppe route. It views nomads not only as intermediaries and facilitators of cross-cultural exchange but also as independent thinkers, inventors, and designers who shaped an increasingly global Eurasian world and exerted influence on their agrarian neighbors. We often assume that pastoralists are culturally “engulfed” or overshadowed by neighboring sedentary giants like China or Persia. The archaeological and historical records tell us otherwise.

My inquiries revolve around “animal style art”. This is a unique approach to image-making invented in the nomadic cultural core and later transmitted to sedentary power players like China. In the nomadic repertoire, animal bodies exist in a constant state of flux, they are crowded, condescend, inverted, and often conveyed metonymically. This fantastic biota was rooted in the nomads’ psychology of mobility and their regular encounters with different environments; in some cases, this alternative ecological reality was a visual response to climate change or political crises. The nomadic elite also used animal-style gold as cultural and political capital, and so did the aristocracy of their geopolitical rivals. A nomadic burial became a zoomorphic spectacle that helped the steppe elite manufacture collective memory in their unstable and reluctant alliances. My second avenue of inquiry in the book has to do with artistic diffusion and receptivity. I show my readers why China was especially swift in buying into the nomadic market and much more successful in doing so than other Eurasian empires – it all has to do with how efficiently the Chinese patrons adapted nomadic zoomorphism to their native aesthetic systems.

What inspired you to research this area?

I was originally trained as a sinologist. So, when I started my PhD, I was first drawn to topics that reflected that training and were admittedly very Sino-centric. However, several serendipitous encounters changed the trajectory of my work. One night, while researching in the Penn library, I came across the book The Deer Goddess of Ancient Siberia by Esther Jacobson. The book opened a whole new world to me, and, in retrospect, it might have been the catalyst for my future projects. Just a week after checking the book out of the library, I came across the stunning Scythian treasures in my advisor’s graduate seminar. Nomads seemed like the perpetual “blindspot” of Asian art history, living in a constant state of “in-betweenness”. The more I searched for books that dealt exclusively with nomadic art, the more perplexed I became by how few scholarly works existed beyond the occasional museum catalog. The challenges in studying the material are indeed numerous – starting with the language. My professors helped me recognize that as a speaker and reader of Chinese, Russian, and Japanese, I was able to access important and largely understudied sources on ancient nomadic lives. And, as I was expanding the scope of my study, I realized that my mother tongue Bulgarian and my elementary proficiency in Mongolian might also help me on this path. Overall, I would say that I owe my passion for the subject to my love of studying languages, and to my professors’ guidance.

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

My research took me on an exciting voyage across Eurasia. I visited sites and museums in Kazakhstan, China, Russia, Mongolia, South Korea, Uzbekistan, and Turkey. I made many meaningful connections with scholars around the world. During my fieldwork, I also realized how little of the material in countries that were once on the other side of the Iron Curtain has entered mainstream academic discourse in North America and Western Europe. On a personal note, studying this material also made me realize my own “in-betweenness” – born and raised in Bulgaria, I moved to the US at the age of eighteen to pursue my higher education and have lived here ever since. While researching nomadic culture, I have more than once contemplated how my own story of being a “perpetual Other” born in the former Eastern Bloc has contributed to my interest in bringing marginalized historical voices out of the shadows.

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

I am still amazed by how geographically distant societies and ethnically or culturally unrelated groups embraced the same zoomorphic motifs. I am especially drawn to the peculiar “deer-bird antler” motif which features extensively in my second chapter: raptor heads emerge out of stylized deer antlers. We find it virtually everywhere on and beyond the steppe.

Has your research in this area changed the way you see the world today?

Undertaking this unprecedented journey across time and space taught me to be more daring in my academic pursuits, and not to fear asking bold questions or challenge canonical narratives. I started this project with some anxiety and trepidation, wondering whether I could ever build those bridges or study so many distinct nomadic cultures. In the end, I emerged an infinitely more confident and intellectually curious individual. Working on my book has also shaped my approach to teaching. Just like I view Central Asia as a hotbed for cultural interaction, I also view my classroom as a cultural cauldron of sorts, a place where a shared interest in understudied places and peoples is fostered and nurtured.

What’s next for you?

I am working on two new books. One is a monograph on hoards along the Silk Roads, and one is a short study of propaganda art in 20th-century Central Asia entitled Posters, Politics and Pioneers: Orientalist Visions of the Other in Interwar Central Asia.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the book

Explores the zoomorphic imagination and image-making of Eurasian nomads and their dynamic interactions with neighbouring sedentary empires

Fantastic Fauna from China to Crimea shows how a shared fluency in animal-style design became a status-defining symbol and a bonding agent in opportunistic nomadic alliances, and was later adopted by their sedentary neighbours to showcase worldliness and control over the “Other”. In this study of enormous geographical scope, the author raises broader questions about the place of nomadic societies in the art-historical canon.

About the author

Petya Andreeva is Assistant Professor of Asian Art at Vassar College. She earned her PhD from the University of Pennsylvania. Andreeva’s work has received awards from UNESCO, the Getty, the American Center of Learned Societies, and the International Convention of Asia Scholars.