by Jackie Watson

The author of Epistolary Courtiership and Dramatic Letters explains what the story of Thomas Overbury reveals about success at the court of James VI and I.

Born in the reign of Elizabeth I, Thomas Overbury began his career under her Scottish successor, King James. His life shows us how the path to success changed as the older regime was replaced by that of a very different monarch. A life written about, analysed and criticised. A life that was influential on the staged idea of courtiership.

The homosocial Jacobean court

In the letters this book takes as its central evidence, it is easy to see that James’s court offers new opportunities for bright young men. After some years with almost no change of political personnel in the final years of Elizabeth, men such as Thomas Overbury suddenly had the chance to shine. He was ready and prepared to seize that opportunity. Born in 1581 in the Midlands, he studied in Oxford and learnt law in London, at the Inns of Court – like many of his generation, benefiting from humanist learning and developing classically-inspired rhetorical skill in a context that was almost exclusively male. He could speak and write well; he had an agile mind; and he was handsome. These things, it seemed, opened doors at the Jacobean court. King James liked to surround himself with such men, and Thomas was rewarded quickly. His success, though, did not go unnoticed.

Social mobility

Overbury had been born into a middling family. The eldest son of a lawyer, Middle Templar Nicholas Overbury, Thomas was to thrive at the new court and benefit his family. Knighted before his father, given lavish presents by visiting royalty, and preferred to positions of influence, Thomas’s success was stellar. Soon he was the man whose support others needed to succeed. The much older and more experienced Sir Henry Neville, for instance, would have liked to become the king’s secretary on the death of Robert Cecil in 1612. Whom did he feel he needed to support his case? Thomas Overbury. Neville spent months writing flattering letters and pursued him around the country as Overbury followed the king’s hunting expeditions.

Enemies at court

Overbury’s power lay in his close friendship with King James’s favourite, Sir Robert Carr. This relationship was a close one and enabled both men to rise socially, but in the process, it bred jealousy and dislike. Ambitious men such as Francis Bacon resented Overbury’s power and his ‘insolence’, and letters written by court commentators show evidence that this resentment was more widespread. Sir Henry Wotton, the recently returned ambassador to Venice, noted to his good friend, Edmund Bacon, for instance, ‘how hard it is to pull’ an ambitious courtier ‘from the bosom of a favourite’ (22 April 1613). He revelled in Overbury’s downfall when, faced by the rising power of the Howard faction at the court, the courtier was arrested and sent to the Tower. Three months later, he was dead, under very suspicious circumstances.

Absolutism and prerogative power

This was a time of legal tension and many legal voices in Jacobean England were worried about the prerogative power of the monarch. The common law was argued by legal commentators to be the birthright of Englishmen in the early seventeenth century, but James VI and I believed in the divine right of kings and considered that he should be able to use his extraordinary powers when he thought fit. Lawyers feared the potential for absolutism. It is in this context that Overbury, technically in ‘contempt’ of the king’s wishes, was arrested without trial, made a close prisoner in the Tower, and, in a relatively short time, died. Though young men in this period had the chance to rise socially in the new opportunities offered by James’s homosocial court, they were also vulnerable to the power of the men in authority whose preferment they sought: particularly the king.

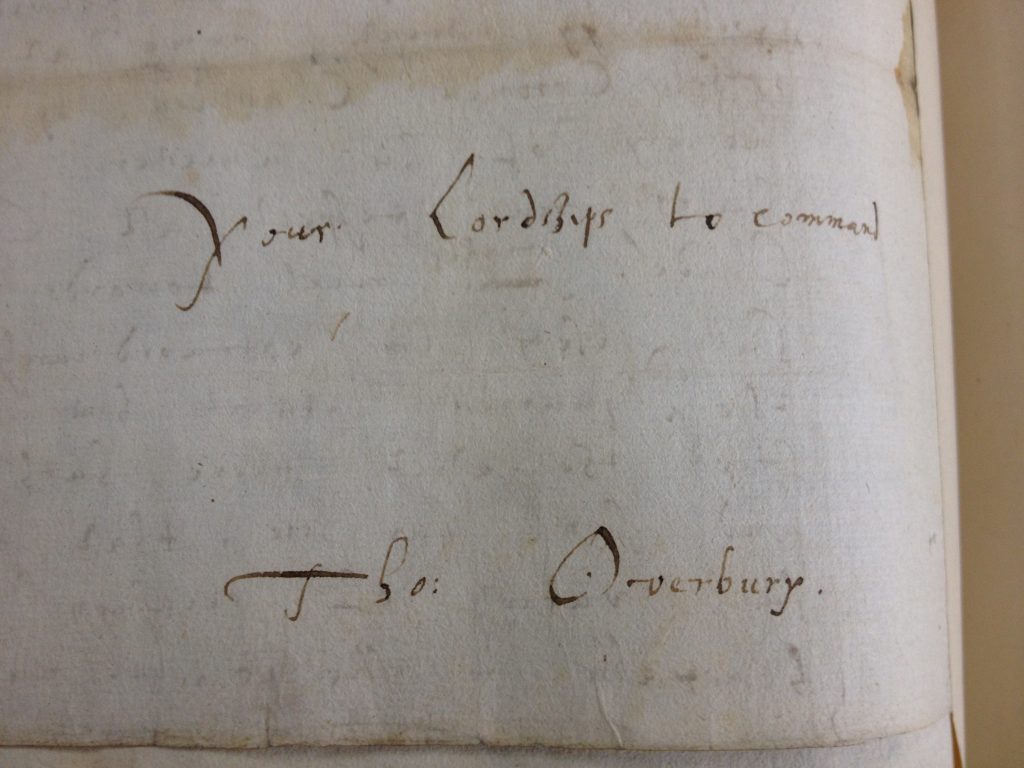

Epistolary evidence and the Jacobean playhouse

The book builds up the context in which Overbury rose, worked, and then fell by looking at the letters written by, to and about him. Building an edited collection of these letters, some of which are newly published, it is possible to see how Overbury built his success and how the resentment of those around him contributed to his downfall. Thus, in the first half, the book looks at the mechanisms of success at the Jacobean court and argues that letters written by men with a humanist education similar to Overbury’s are, in their style and content, inherently dramatic. In the second half, the book goes on to examine how these mechanisms of courtly success are reflected in staged courtiership in the playhouse. First, it looks sat the relationship between the courtier, Camillo, and King Leontes in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. Then it explores the contrasting means of courtly influence presented by Webster through Antonio and Bosola in The Duchess of Malfi. And, finally, the book concludes with a pair of plays written by George Chapman. The Tragedy of Bussy D’Ambois is written as James accedes to the throne and we can see by comparing it to its sequel, written a few years later, how ideas about courtiership have shifted.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the book

Analyses how the political career of Sir Thomas Overbury exposes the changing systems of power at the English court between 1603 and 1613

Through an analysis of the career of the eminent courtier Sir Thomas Overbury, Epistolary Courtiership and Dramatic Letters re-examines what is meant by courtiership in the Jacobean period. With a particular focus on the years between 1609 and 1613, the book brings together many of the letters surrounding the scandal leading to Overbury’s murder and provides an examination of epistolarity in the context of humanist and legal learning.

About the author

Jackie Watson is an independent scholar who researches early modern literature. Her published work focuses on how legal thinking, letter writing and ideas of the senses in this period affect contemporary writing, particularly for the theatre.

I love The Winter’s Tale beyond all reason, but I am always unsure how to judge the actions of the courtier figures, Camillo and Paulina. Certainly both are placed in unenviable predicaments, but on the scale ranging from Honorable to Dishonorable, Loyal to Disloyal, where do their responses to those predicaments fall? So I was happy to find your blog post and book: “Chapter 4: Royal Prerogative and the Role of Counsel in The Winter’s Tale” certainly seems like it would help me to answer that question. Thanks to you for your scholarship and to EUP for producing an inexpensive paperback of your book, which I hope to get my hands on soon.