by Angus Mitchell

In January 1997, Diana, Princess of Wales, undertook a trip to Angola on behalf of the International Committee of the Red Cross. Her mission: to highlight the plight of landmine victims. With an entourage of photographers, journalists, and camera crew, her three-day visit allowed for several curated photo-ops. Her moving interaction with Sandra Thijika, a thirteen-year-old girl who had lost a leg from a random landmine blast, and her unaccompanied walk through a minefield in Huambo were two of the more memorable moments.

Less than nine months after her Angola trip, Diana’s life ended tragically in Paris. But her anti-landmine activism was part of a broader movement that lived on. Before the year was out, the Mine Ban Treaty was signed in Ottawa by 121 countries, and the principal advocates in the International Campaign to Ban Landmines had won the Nobel peace prize. No one doubted that Diana’s intervention lent the issue extraordinary global impetus and showed what celebrity endorsement of a cause could achieve.

Though the campaign to ban landmines remains a significant part of the history of contemporary humanitarian activism, much of its story has been lost to history. Today, Humanitarian Mine Action (HMA) is one of the most generously funded dimensions of the entire development aid sector, and one with immediate and long-term gains for non-combatant communities. However, very little is known about how and where it began.

Soviet Retreat from Afghanistan

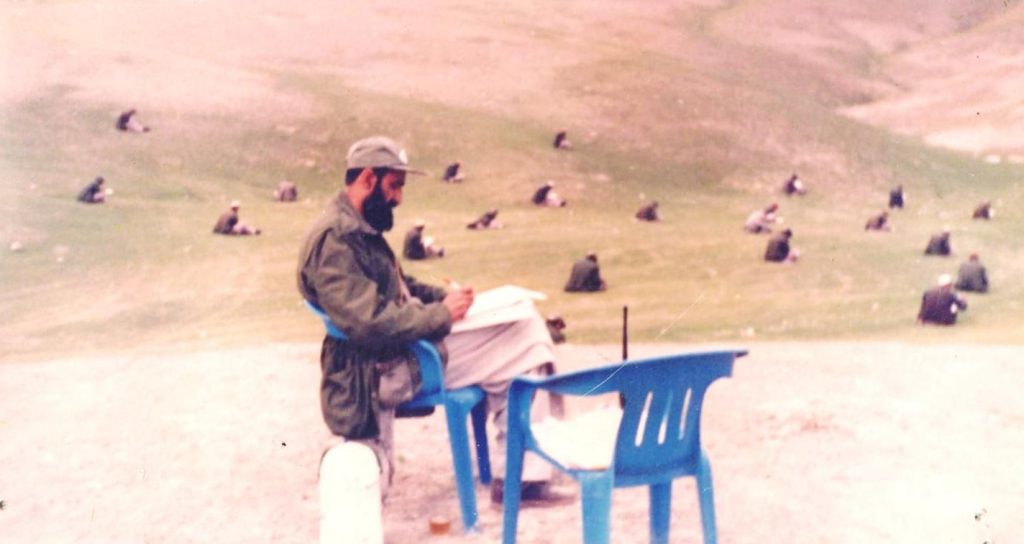

The green shoots of HMA can be traced back to 1988 and the retreat of the Red Army from Afghanistan. A decade of Soviet occupation left behind a country socially and economically ravaged and a mujahideen insurgency that continued to wage war against the Kremlin-supported regime of President Najibullah based in Kabul.

Into this mix was added the UN, who had been tasked under the Geneva Accords to deliver peace and humanitarian aid and undertake the repatriation of nearly five million Afghan refugees living inside the borders with Pakistan and Iran.

The key challenge obstructing the repatriation of refugees was the plague of anti-personnel landmines. Over the previous decade, all sides in the conflict had used these silent sentinels for strategic purposes. Soviet military installations were surrounded by minefields. Mountain paths leading to arable fields, orchards and villages were seeded with mines. The main arterial roads radiating from Kabul were littered with vehicles destroyed by anti-tank mines. The Soviets had air dropped thousands of vicious Butterfly Mines (PFM-1) throughout rural districts that children too often mistook for plastic toys.

Such was the need for prosthetic limbs that old army shell casings were turned into artificial arms and legs for amputees. The UN realised that if the millions of Afghans living on the border of Pakistan were to be repatriated then the mine problem had to be faced and in that realisation the landmine crisis shifted from being a military legacy to becoming a humanitarian priority.

A vital part of this transition came through the early efforts of The HALO Trust, an organisation that established itself in the tense and war-torn suburbs of Kabul. From austere and under-funded beginnings, HALO has grown into to the largest HMA charity in the world. Today, it employs over 10,000 people worldwide and operates in almost thirty countries.

New World Order

Little is known about the early years of de-mining, and of the men and women who worked patiently and often in extreme danger to rebuild war-torn areas of the world. How HMA developed in Afghanistan in the early 1990s became intrinsic to the New World Order that emerged from the post Cold War world and the first Iraq War.

Retrieving the history of an organisation like HALO helps to identify the growing intersections and triangulated interdependencies between development, diplomacy, and defence. From Afghanistan, HMA expanded next into Cambodia, Mozambique, Angola and Transcaucasia. The story embodies a key shift in the aid sector as it moved from the periphery into the centre of international relations.

Disgracefully, the destructive shadow of landmines has never gone away. In 2014 leading mine clearance organisations established a new campaign: “Landmine Free 2025” boldly aspiring to the elimination of landmines. It was signed by the signatories of the 1997 Ottawa Treaty. But the world that people hoped for back in 2014 is not the world we live in now.

Landmines remain a vicious reality. As conflict in Ukraine starts to slip from our news feeds, we cannot lose sight of the massive landmine legacy facing civilians seeking to rebuild peaceful lives in war-weary regions. Along 600 miles of frontline, the Ukraine is now the most heavily mined region in the world.

Supported by generous donations from development aid budgets and philanthropic organisations such as the Warren G. Buffett Foundation and Prince Harry and Meghan’s Archewell, those engaged in HMA shine a beacon of hope during the remorseless reality of endless war.

Read Angus Mitchell’s full article from the Scottish Historical Review.

About the journal

The Scottish Historical Review is the premier journal in the field of Scottish historical studies, covering all periods of Scottish history from the early to the modern, encouraging a variety of historical approaches.

Sign up for TOC alerts, recommend to your library, subscribe to SHR and submit an article.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the author

Angus Mitchell is a historian who lives in Ireland and has published extensively on humanitarian activism in South America and Africa. His work has appeared in The Journal of Victorian Culture, Irish Historical Studies, Field Day Review and the Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Latin American History.