by Sarah Keenan

It’s easy to get lost at the British Museum. The expansive central London building, set out over three floors and divided up into over 60 galleries, displays some 80,000 objects from all over the world. The British Museum being an ‘encyclopaedic’ or ‘universal’ museum which sees itself as a paternalistic safe keeper of the world’s cultural history, many of those objects were obtained as trophies or specimens during British colonial rule on terms which many contemporary commentators describe as pillage and theft. The 80,000 objects on display make up a tiny sliver of this institution’s property: 99% of the British Museum’s collection of over 8 million objects is kept in storage.

The British Museum itself struggles to keep track of and secure its vast collection, as its recent loss of more than 2000 items from its gems and jewellery section showed. In the wake of the lost gems and jewellery, a number of groups who have long been campaigning for the repatriation of their objects from the museum reiterated their claims, pointing out that the loss undermines the British Museum’s claim to be better able to care for these objects than their places of origin. While I agree with the claims of those campaigns, in my article I argue that the problem goes deeper than the British Museum’s evident inability to adequately record and care for the objects in its collection, to the museum’s fundamental role as the possessive keeper of property.

My research has revolved around another object lost at the British Museum: the Gweagal shield. Unlike the lost gems and jewellery, this Aboriginal bark shield is still physically in the British Museum building – pinned against a wall, behind glass in the Enlightenment Room – but it has been lost in a different way. The shield is one of the museum’s most prized objects, having been on display since the 1970s, with the narrative that it was used by one of two Gweagal men who faced James Cook when he first landed on the continent now known as Australia, in April 1770.

As an Aboriginal artefact from this crucial moment in history, the shield has come to be meaningful to many, including Gweagal man Rodney Kelly, who travelled to London in October 2016 to submit a repatriation request for it. As my research shows, almost immediately following Kelly’s request, the British Museum began conducting new research into the shield’s provenance, including holding a closed workshop in May 2017 with invited experts chosen by the museum. In March 2018, two articles authored by participants at that workshop were published in Australian Historical Studies, each casting doubt on the shield’s identity, claiming that it is in fact very unlikely the shield used to defend Cook’s landing. These articles suggest that ‘the real’ Gweagal shield has been lost, somewhere between being brought to London on the Endeavour in 1771 and being misidentified by the British Museum in the 1900s.

I critically examine these two articles, within the broader context of the shield’s story. Examining both the conceptual frameworks used for the new research into the shield’s provenance and the material context in which the research was produced, I argue that the truth of the shield cannot be found while it remains in the possession of the British Museum, because the museum’s keeping of the shield involves it being conceptually and materially rendered an object of property.

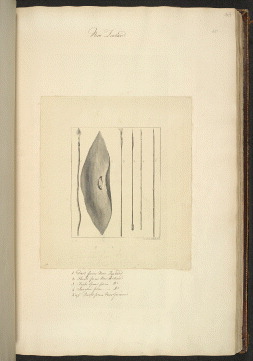

The first article makes the key empirical case that the shield is not the one from Cook’s landing. The author asserts that it does not accurately match this 1771 drawing of that shield, by the draughtsman employed by Joseph Banks to draw artefacts brought back on the Endeavour.

The second article accepts the empirical conclusions of the first, and offers a cultural history reading of how the British Museum shield came to be Cook-related even though it is not ‘really’ the Gweagal shield. Together, the articles have the effect of undermining Kelly’s repatriation claim. Kelly’s claim is for the Gweagal shield, and the articles argue that this is not the Gweagal shield after all.

I argue that both articles are reliant on an onto-epistemological framework in which objects have a discernible empirical truth which is separate from and superior to their affective, culturally and discursively attached meaning. This framework is contestable. There are other ways of understanding objects, their agencies and identities. Most significantly, there are Indigenous ways of knowing and understanding objects and ‘truth’ which are distinct from the empirical approach relied on in these articles.

Other ways of knowing the shield are possible, but while kept under glass in London they remain lost within the linear history and proprietal view of the world which the British Museum champions. It will only be possible to find the ‘truth’ of the Gweagal shield once it is no longer the property of the British Museum.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the author

Raised on Giabal and Jarowair land in Toowoomba, ‘Australia’, Sarah Keenan is now based in London where she is a Visiting Reader at Birkbeck Law School, a Fellow at Institute of Advanced Legal Studies and a Visitor at Oxford Centre for Socio-Legal Studies.

About the journal

An international journal with a strong regional base, Legalities publishes contextually sensitive, theoretically informed, critically engaged and interdisciplinary socio-legal scholarship.

Sign up for TOC alerts, subscribe to LEGAL, recommend to your library, and learn how to submit.