A Q&A with Heba Arafa Abdelfattah

In this author Q&A, Heba Arafa Abdelfattah introduces her latest book, Filming Modernity and Islam in Colonial Egypt, which explores the formative years of Egyptian film (1919–52) to contest the contradiction between Islam and innovation.

Tell us a bit about your book

Filming Modernity and Islam in Colonial Egypt tries to understand the survival story of a group of creative minds, many of whom identified as Muslims and see no contradictions between their art and their religion. Thus, I tried to understand what kind of philosophies, experiences and intellectual exchanges they encountered that allowed them to create a film industry under colonisation and war. And what made their films popular until today?

What inspired you to research Egyptian film and filmmakers of this period?

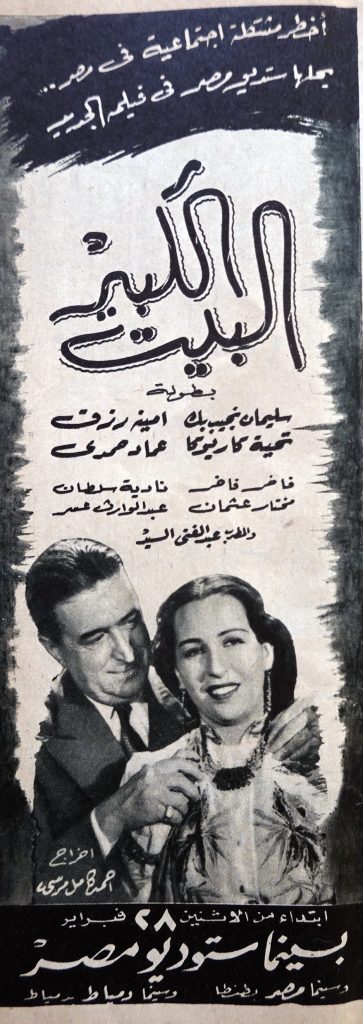

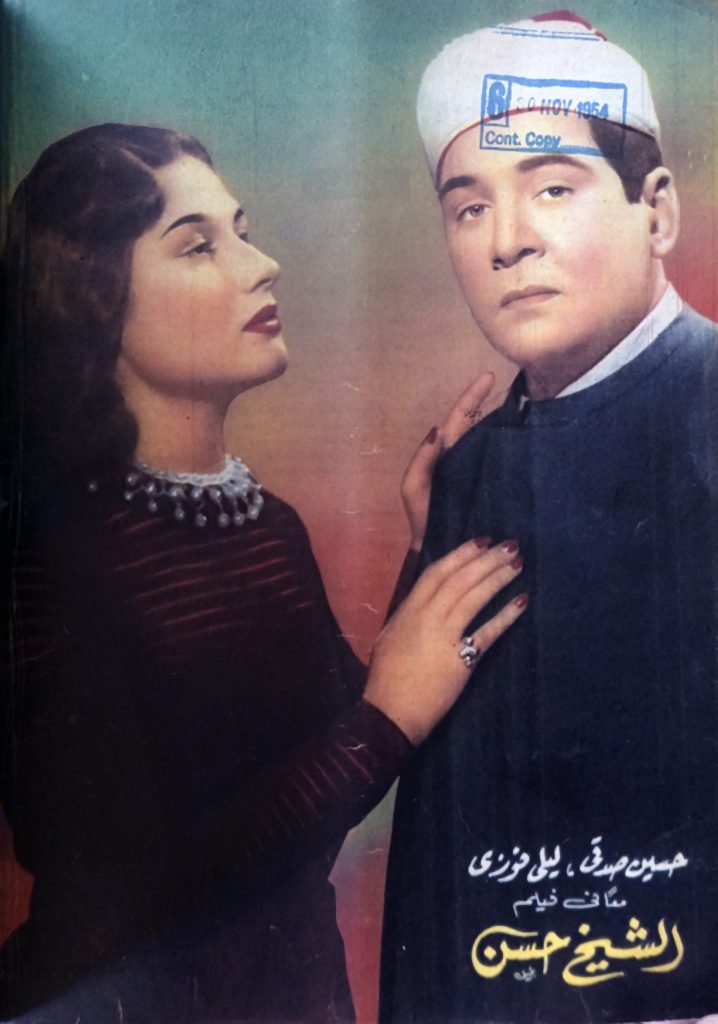

I missed the presence of a book that tells the story of modernity in Egypt through the voice of its filmmakers. I also missed seeing a book on the history of Egypt and its public culture in the colonial period with the names and faces of actors that I grew up watching. Sometimes, I used to ask myself, ’Where are Fardus Muhammad, Istfan Rusti, Sulayman Naguib, Muhammad Kamal al-Masri, Zaki Rustum, Yusuf Wahbi, Naguib al-Rihani?’

It is not that my colleagues in the field did not mention or occasionally write about these figures. However, I was eager to see a focus on their roles. Their contributions are the backbone of the region’s cultures of modernity. I was also intrigued by the fact that, despite the many geopolitical transformations in the MENA region and the rising religious discourse against the performing arts, Egyptian film classics never ceased to entertain. People, whenever they joke or talk in everyday life, refer to the lines of these black and white classics.

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

There were many exciting moments. The most exciting were the moments I better understood my ideas as I rewrote them repeatedly. Watching the process of interpretation happen was so cool that I fell in love with hermeneutics. It is such a rewarding experience. The time spent in the archives, whether in the UK or Egypt, was also remarkable.

Did you get exclusive access to any new or hard-to-find sources?

Yes, much of the data in the book is new. I especially recall how I discovered all the material on Rivoli cinema: I was lucky enough to find information on this theater in the Kew Garden and Cairo archives. I got access to some rare records of Akhir Sa’a, which included rare footage of the co-owners of the cinema, the brothers Ga’afar. Unfortunately, I could not include this in the book because it was a microfilm copy, and it was quite difficult to renovate it so that it could be printed with relatively acceptable quality.

Did your research take you to any unexpected places or unusual situations?

There were some funny moments. While working in the Kew Garden Archives, a misunderstanding occurred over my accommodation. On the last day of my visit, I was very short on money. The plan was to go to the archive to work until 3:00 p.m., come back early to pack and catch my flight next morning. That day, a very harsh knock on the door woke me up at 6:00 a.m. The landlady came loaded with cleaning tools, supplies, and bedsheets to prepare the room for the next guest. After 5 minutes of exchange, it turned out that there was a misunderstanding over the number of nights booked. Realising her mistake, she moved me to another room.

As much as I was happy to spend my day in the archives as planned, I was a lot happier that I wouldn’t have to pay for an extra night! I could not help remembering a scene in the movie Si Omar/Mr. Omar when Nagib al-Rihani was pickpocketed in his hotel room overnight and the hotel owner came in the morning to collect the bill. The rule was either to pay the amount in full or the customer will be dragged downstairs to clean the basement of the hotel. Luckily, the thief in the movie was generous and paid the hotel bill before taking off with the wallet. And luckily, for me, I had paid my stay in full upon booking. Anyway, nobody was hurt, and all ended well!

Has your research in Egyptian film and your writing process changed the way you see the world today?

I think so. A fascinating Egyptian proverb reads ’widn min tin wa widn min ‘agin’, meaning ‘have one ear of mud and another ear of dough’. I used to think that the proverb encourages people to be indifferent or to give up. After working for years on this book, I realised that the proverb is an invitation to focus.

Writing a book can be compared to driving; one can have a license, know how to drive and enjoy driving, but the only guarantee to arrive safely at your destination is to overlook any forces of distraction and to focus on the road, i.e., ‘have an ear of mud and ear of dough’.

About the book

Filming Modernity and Islam in Colonial Egypt

Heba Arafa Abdelfattah

Get 30% off Filming Modernity and Islam in Colonial Egypt with discount code NEW30

Explores the formative years of Egyptian cinema (1919–52) to contest the contradiction between Islam and innovation

About the author

Dr Heba Arafa Abdelfattah graduated from Georgetown University in the Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies in 2017. Her research interests fall within the interdisciplinary area of humanities, focusing on the philosophy of religion and the philosophy of art as articulated in Arabic and Islamic thought in all its expressions (from the 7th to the 21st centuries). She works with sacred scripture, literary texts, archival documents, films and other forms of artistic and cultural production to understand creative experiences at the intersection of discourses of modernity and religious mores. Her articles appeared in such peer-reviewed journals as Religions, Review of Middle East Studies, International Journal of Communication and the Journal of Islamic and Muslim Studies (JIMS).

Dr. Abdelfattah served as visiting assistant professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology. She was also a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute of Sacred Music and a lecturer in the Department of Religious Studies at Yale University. She has been an assistant professor in the Division of Humanities at Grinnell College since 2022.

Keep in touch

Sign up to our mailing list for the latest on Edinburgh University Press’s books and journals, events and special offers.