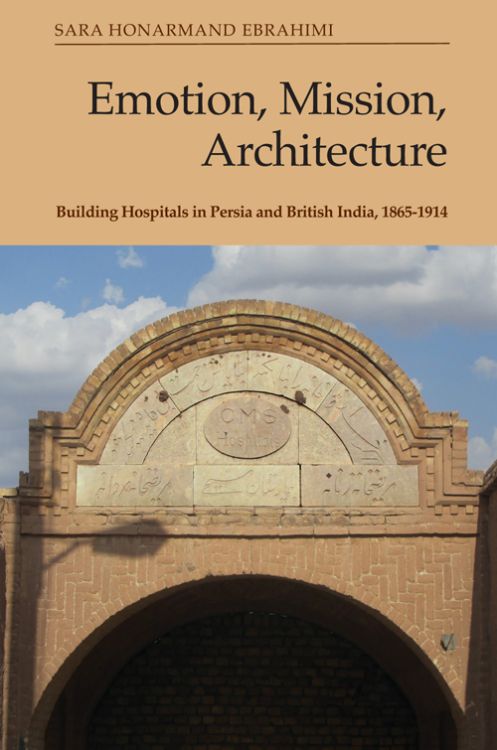

by Sara Honarmand Ebrahimi

How did patients feel when visiting mission hospitals built by British missionaries in Asia and Africa in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? I am preoccupied with this question in my book, Emotion, Mission, Architecture: Building Hospitals in Persia and British India, 1865-1914. I explore mission hospitals built by the London-based Church Missionary Society (CMS) in Persia and North-western British India and argue that they should be viewed as ‘emotional setups’ that changed the sensory relationship between missionaries and local people.

In so doing, I offer additional answers to questions of why medical missions developed in a specific way, why the missionaries opted for one region, and city or town over another, why certain architectural forms were privileged over others. While the book focuses on missionaries’ side of the story, it also discusses, to some extent, how it felt to stay in a mission hospital, showing we can speculate about indigenous perspectives by focusing on feelings.

by the author

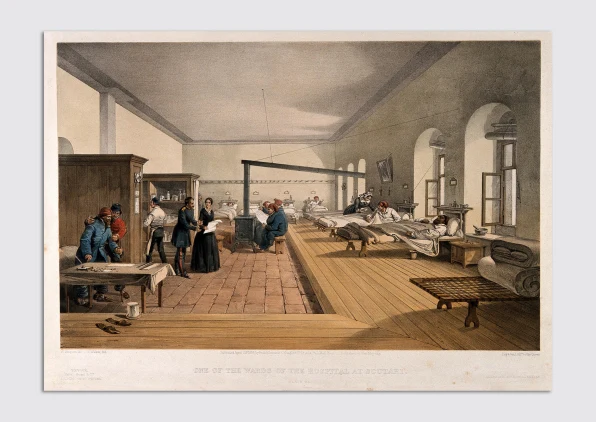

Mission hospitals were developed slowly. Medical missionaries first undertook many itineration tours, after which they started small outpatient dispensaries, followed by an inpatient department in rented buildings and, finally, a purpose-built structure. Various reasons – financial, practical and socio-political – were involved. The missionaries had limited resources, both of people and funds. They also faced opposition from local people. But there was another, more strategical, reason relating to missionaries’ desire to attract as many patients as possible. They viewed undertaking itineration tours, opening dispensaries, and working in rented buildings as important for establishing a ground upon which to establish a hospital. These practices provided social settings for interaction and, through interaction, for perception and sensation between missionaries and local people. Without them, missionaries would have been unable to construct purpose-build structures and establish ‘permanent’ hospitals.

When, after several years of working in rented buildings, missionaries decided to construct a purpose-built hospital, they still could not dismiss local people’s feelings. This had architectural implications. Missionaries adopted local architectural forms and elements that were thoroughly caught up in the daily lives of the local people, such as Islamic four-part gardens, Persian courtyard houses, or the Kermani arch. They also employed and developed a wide range of construction methods and different types of hospital plans and ward designs such as the ‘serai-system’ and the ‘purdah hospital’. In all these, missionaries disregarded their sanitary approaches in favour of patients’ feelings and need to facilitate certain practices and attract the patients. For example, the serai-system was designed like a caravanserai – an inn for travellers built along the caravan routes in Central Asia and the Middle East – where patients could stay with their family and friends.

While missionaries found the presence of close associates irksome, they allowed them to accompany the patients and stay in the hospitals because this plan would increase the number of people with whom they came into contact. These variations and innovations expand the historiography of British hospital architecture in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which has predominantly been about the pavilion plan hospital. The claim that the pavilion plan became an international standard by the late nineteenth century excludes mission hospitals.

by the author

These variations and innovations also add to our understanding of the relationship between missionary medicine and empire. If we zoom out and contemplate the geographical location of the hospitals, it becomes apparent that missionaries’ desire to attract patients also played out at the macro level. It became ‘stuck’ to particular locations and thus people, such as ‘the Pashtun and Baloch tribal groups’. Through attracting them to the hospitals, the missionaries’ hope was to generate a community in favour of the colonial establishment.

In short, the book demonstrates that focusing on a lack of resources, local people’s opposition, the absence of professional architects, climatic conditions, or these supposedly hard and rational things, makes us lose sight of some historical realities. We can offer more nuanced discussions of why male and female missionaries did what they did by turning to feelings. The history of emotions also prevents us from generalising the relationship between architecture and emotions and instead considers how it changes over time and is different from one person to another. Like other studies on the history of emotions, this book’s central goal has been to show that excluding emotions from our historical analysis leaves us impoverished.

About the book

| Order your copy Emotion, Mission, Architecture by Sara Honarmand Ebrahimi is an n innovative history of medical mission from the perspective of the history of emotions |

About the author

Sara Honarmand Ebrahimi is a Humboldt Research Fellow at Art History Institute, Goethe Universität Frankfurt am Main. Previously, she was a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at University College Dublin (2021-22), and a Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Edinburgh (2019-20). She studied for her PhD in University College Dublin, where she was an Irish Research Council (IRC) doctoral scholar. Her research interests address the multifaceted origins of ideas and practices in the history of international health and architecture and consider the history of emotions as a way of doing architectural history.