by Dženita Karić

As I was doing research on the Hajj discourses in Bosnia from the 16th to the 21st century, I encountered a range of texts, published and unpublished, in Bosnian, Arabic and Ottoman Turkish languages. Some of the texts were kept in well ordered institutions, such as manuscript libraries in Istanbul and Sarajevo. Some could be found on the bookshelves of middle-class Bosnians as part of the small, but well curated private libraries of Islamic books, and some were simply too difficult to find, having been printed in less than one hundred copies and shared only amongst family and friends.

Multiple Paths to the Holy

Despite their modest circulation, the Hajj travelogues of Bosnian Muslims reveal themselves to be repositories of rich and varied knowledge on the Bosnian experience of lived Islam in the 20th century. Sometimes being the only piece of literary or factual writing an individual would produce in their lifetime, Hajj travelogues reflected both theinfluence of social, political and cultural forces onto the ”common person”, as well as the continuous ties of devotion and obligation to the holy places of Mecca and Medina. In the process, the Hajj writings had multiple purposes: they served as aide-mémoire, a way to extend the unique pilgrimage event, to offer instruction to the generations of future pilgrims, and to cultivate the feeling of attachment to Hijaz amongst the local population. One such work was a collection of different writings by Hafiz Hadži Zaim-efendija Huskanović (1915-1987), edited by Osman Kavazović in 2018, and practically unknown beyond the very small local community of the time.

Hafiz Hadži Zaim-efendija Huskanović was a local imam in northern Bosnia. As we find out from the poem he wrote about his life, he was born in the turmoils of the First World War in a small village. Per his mother’s wishes, he went to a madrasa and then was married to a local girl. The song proceeds swiftly from verses on his father’s pilgrimage, his wife being the first woman to visit the regional hospital, to his recruitment into the Royal Yugoslav Army. Once in active service in 1941, the army breaks down in front of German forces: Hafiz Zaim-efendija is sent to a labour camp in Bavaria. While his wartime woes were described in verse, Hafiz Zaim’s other key life events, including his two Hajj travels, were described in prose. This allowed him to present his Hajj experiences in a semi-documentarist style, and include information on pilgrims and the organisation of Hajj travel.

The Hajj was no small feat in socialist Yugoslavia: it was expensive and it was tightly controlled by the state. Yet, despite these obstacles, the pilgrimage itself was influential and impactful for the whole local Bosnian community, who participated in the event through farewell ceremonies of ikrar prayer, and who was also brought in presence of the sacred through Hajj stories and objects brought from Mecca and Medina as gifts. Hajji Huskanović even lists the numerous items he brought from Hajj, including hundreds of prayer beads, pieces of kohl, and headscarves. Through words and objects, even those who would never go on a pilgrimage – and that was the vast majority of Bosnian Muslims in the past and present – could cultivate their attachment to Hijaz.

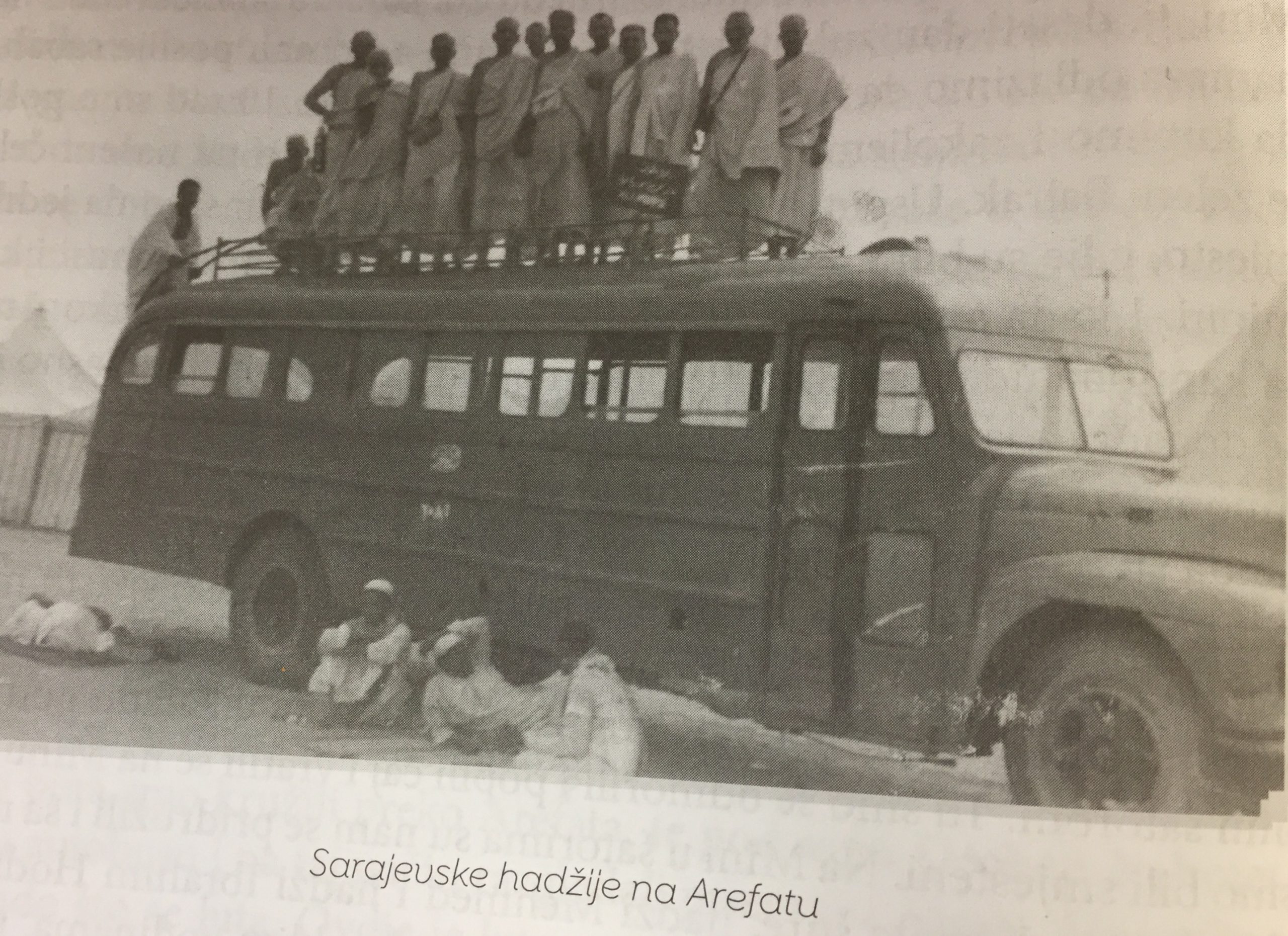

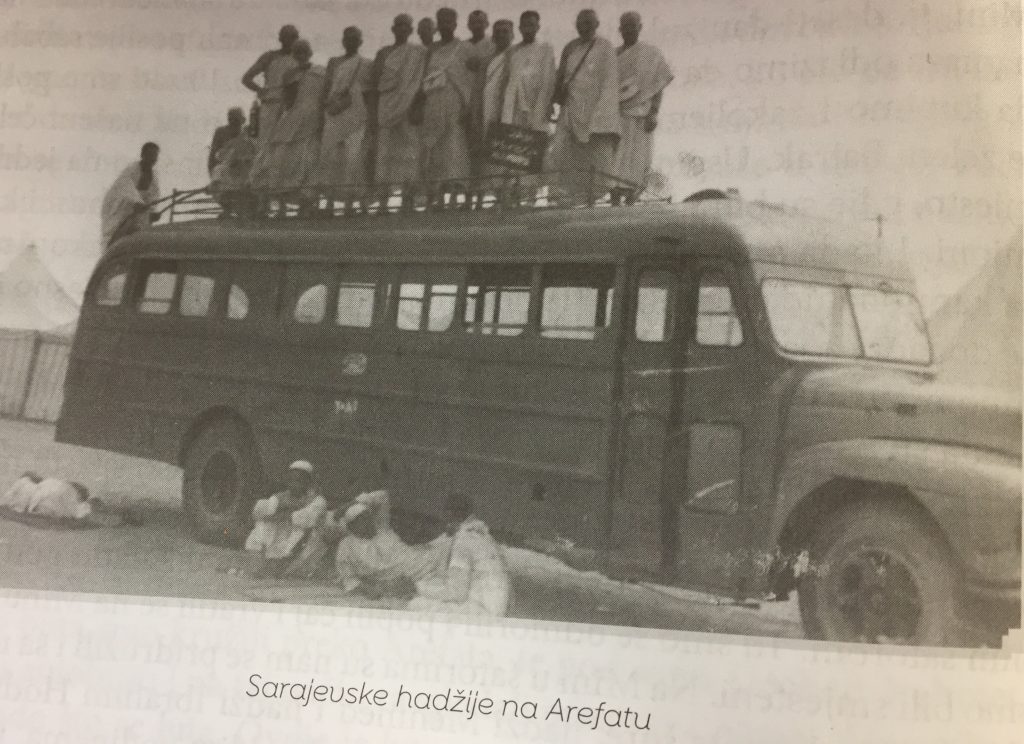

Hafiz Zaim-efendija took pictures during both his Hajj travels, with the additional aim to document the journey. The Hajj journey has always been closely accompanied by technological improvements: modern day Hajjis very often use smartphones to record their moments close to the Ka’ba. The means of transport also play a significant role in the Hajj journey: like many anxious fliers, some Hajjis in Huskanović’s travelogue also thought that they were living their last moments while waiting for embarking. Yet with the joy of arriving in Mecca and Medina, the Hajjis would overcome all difficulties: these moments were often described as overflowing with emotions, even leading to a certain kind of unconsciousness and paralysis. Authors such as Hafiz Zaim-efendija paid close attention to every detail, aiming not only to provide information but also to convey the atmosphere of the meeting at the holy places.

Mecca and Medina were not the only places of Islamic geography relevant to the Hajjis. Many 20th century Bosnian Hajjis felt conflicted – both enchanted and confused – with the modern realities of Cairo, Damascus and Istanbul. However, like their premodern predecessors, they aimed to find interlocutors amongst the scholars residing in these cities. Bosnian Hajjis did not only observe but were also observed: Huskanović mentions how Cairene traders would call them by the name of the Yugoslav president Tito, trying to lure them into buying trinkets.

Hafiz Zaim-efendija’s travelogue is a testimony to one of the ways in which the Bosnian Muslim community continued to preserve Islamic values and practices in sometimes challenging times. It was not the only medium of religious experience – Hajj was also the subject of numerous learned debates, reportages, essays and critical considerations, all of which have added myriad meanings to the pilgrimage and perhaps influenced larger Bosnian readerships. Yet, in an unparalleled way, the writings of local authors like Hafiz Zaim-efendija Huskanović show that Hajj proved to be a democratising inspiration that defied the constrictions of daily life.

About the book

Shortlisted for the 2024 Muslim World Book Award

Bosnian Hajj Literature, Multiple Paths to the Holy explores changing attitudes to the holy through a study of five centuries of Bosnian Hajj literature and redefines the ways pilgrimage can be understood and offers new methods for investigating the meaning and importance of Hajj for generations of premodern and modern believers. It also throws light on Balkan communities previously ignored by modern scholarship in Islamic, religious, and area studies. Breaking with the predominant academic trends of focusing on nationalism and ethnic conflict in the region, it instead puts the spotlight on the richness of texts, and visual and archival material, and focuses on genres that challenge the established literary canons.

About the author

Dženita Karić is a senior researcher at the Berlin Institute for Islamic Theology, Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. She has published articles in the British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Archiv Orientalni, Prilozi za orijentalnu filologiju, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Women, Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History (Brill), and Cultural History (forthcoming). She has also contributed to the edited volumes Muslim Women’s Pilgrimage to Mecca and Beyond: Reconfiguring Gender, Religion, and Mobility (ed. Marjo Buitelaar, Manja Stephan-Emmrich, Viola Thimm, Routledge 2020) and Muslim Pilgrimage in Europe (ed. Ingvild Flaskerud and Richard J. Natvig, Routledge 2016).

Sign up for our mailing list!

Want to hear more about what we’re publishing? Sign up to our mailing list! You’ll be the first to hear about new books, blog posts and events.