by Albert Pionke

The US has just emerged from a mid-term election cycle. In the UK, calls for a general election grow ever louder. Politicians, pundits, and pollsters alike cite the discontent of the middle class with, depending upon one’s ideological predilections, the present administration, the previous administration, the state of the economy, the decline of civil society, the supposed threats to national identity, the supposed threats to individual liberty, the business environment, the natural environment, democracy itself, and the list goes on.

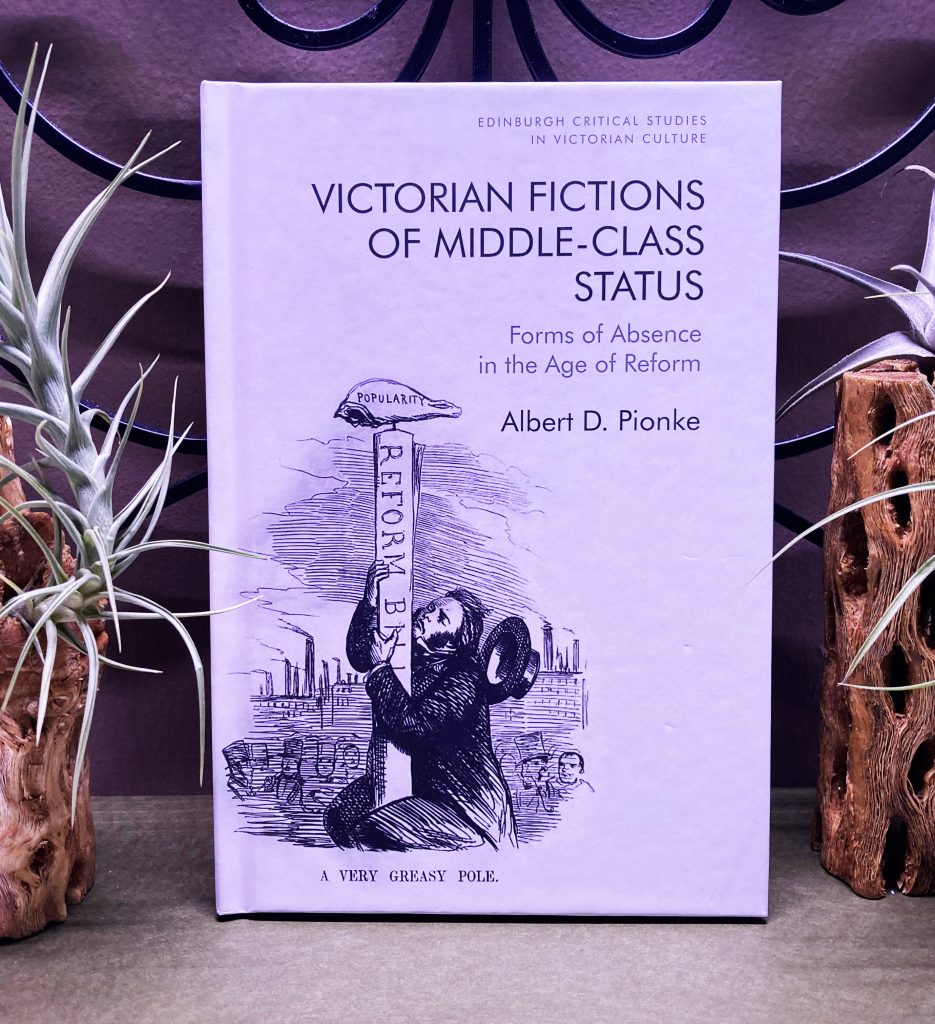

Lost in the noise is a more basic question: what is this often-cited but never-defined bloc called the “middle class” and how did it become so important? As is so often the case, this pressing present question has its roots in the Victorian past. Although most historians agree that the language of class, as distinct from the language of rank or degree, arose in the late eighteenth century, it was not until the Representation of the People Act of 1832 (aka, the First Reform Act) that the middle class was recognized in Britain by statute.

The £10 franchise established a floor for middle-class status. And members quickly sought to perform their deserts as Britain’s newest electors by positioning themselves at the moral center of subsequent key debates, including global abolitionism and the repeal of the Corn Laws, and at the financial center of key patterns of consumption. To be a member of the middle class was to attend church services and self-improvement lectures with equal regularity, to join voluntary societies and subscribe to charities, to send one’s sons to boarding schools and prepare one’s daughters for the marriage market, to purchase pianofortes, pinafores, and the service of at least one domestic servant.

And, since all this took money—by most accounts a minimum of £300 per year—to work vigorously, to save rigorously, to invest sagaciously, and to guard assiduously against any of fortune’s slings and arrows that might outrageously remove one from this recently-enfranchised social middle and back to the un-Reformed. To be a member of the middle class in Victorian Britain was always to be a little nervous about the security of one’s social position.

Victorian Fictions of Middle-Class Status recaptures this sense of instability at the center of Victorian society. Rather than documenting confident assertions of middle-classness, it tracks the anxious negations by which novelists and other writers sought to define the limits of the class to which they also aspired to belong. To be middle class in Victorian fiction was to repudiate the overdetermining legacy of noble birth, the unalloyed pursuit of material wealth, the threatening power of physical or numerical force, the normalizing tendency of statistical fact, and, for women—even, surprisingly, for women represented by progressive authors—the aspiration for masculine authority.

Addressing multiple subgenres of the Victorian novel, including orphan narratives, financial fiction, social problem novels, domestic realism, and a genre-crossing cross-section of fiction by and about women, the book offers fresh readings of novels by Charlotte Brontë, Wilkie Collins, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Elizabeth Gaskell, William North, Anthony Trollope, William Makepeace Thackeray, Charlotte Yonge, and others. What these writers knew that more modern politicos have forgotten is that the middle class has always been discontented, and has always solaced itself with fictions of its own making.

About the author

Albert D. Pionke is the William and Margaret Going Endowed Professor of English at the University of Alabama.