By Stephanie Peebles Tavera

My home state of Texas has become an epicenter for book challenges and abortion bans. These are not mutually exclusive acts of gender and racial oppression. In fact, they have a precedent in the form of the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use (Ch. 258, § 2, 17 Stat. 599). Called the Comstock law for short, in honor of its lobbyist and enforcer Anthony Comstock, the law banned access to abortion and birth control and shutdown the production and circulation of literature about reproductive health. After all, he who controls knowledge about sexual health, controls the birthrate of a population and can condition the production of the elite class versus the working class.

This isn’t The Handmaid’s Tale. It’s Brave New World. But without soma.

Fiction writers have been on the frontlines fighting book challenges and abortion bans since the passing of Comstock law in March 1873. In fact, Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Women, was one of the first authors to call out conservative politicians for shutting down access to reproductive healthcare and sexual knowledge. Alcott was not alone. Several women writers of medical fiction give us a playbook for how to fight censorship, stop living in the nineteenth century, and maybe avoid a dystopian future, too:

1. Make every moment a (sex ed) “teaching moment.”

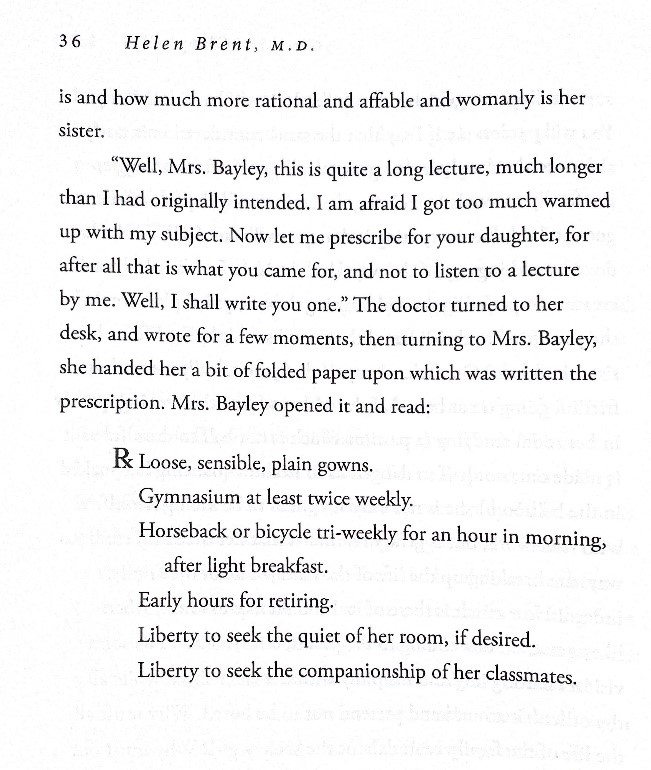

If you are medical professional or sex-pert, you should take every opportunity to squeeze sexual health into the conversation. And I mean every opportunity:Treating patients in a clinical setting (see Annie Nathan Meyer’s Helen Brent, M.D. [1892] or Elizabeth Stuart Phelps’ Doctor Zay [1882]). Teaching a human anatomy and physiology class to a captive audience (see Louisa May Alcott’s Eight Cousins [1875] or Rebecca Harding Davis’ Kitty’s Choice: A Story of Berrytown [1874]). Or just casually meeting a girlfriend for lunch (see Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Crux [1911]). It’s good public health policy! Some will write you off as a “visibly agitated” woman spouting mere “flummery” (Davis 34, 33), while others will welcome your advice for saving them from marriage to a syphilitic (Gilman 128-130). Nineteenth-century scenarios aside, women writers of medical fiction emphasize a shared truth: Women want knowledge about their bodies. They just don’t always know who or how to ask for it.

2. Build coalitions with your audience

Long before the publication of the Combahee River Collective Statement (1977), Frances Ellen Watkins Harper recognized the power of collective action. Her public speeches and activist essays highlight how the Women’s Crusade for temperance started in earnest in 1873, the timeliness of which – not incidentally – aligns with the passing of Comstock law. It wasn’t lost on Watkins Harper that taking away a woman’s right to reproductive healthcare is not an act of morality but misogyny. Just like forcing a widow to pay her husband’s debt. Or trapping a woman in marriage to an alcoholic. Watkins Harper’s public speeches and essays often appeal to specific audiences, whether of white women (see “We Are All Bound Up Together” [1866]) or black men (see “The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the Colored Woman” [1888]).

But in Iola Leroy (1892) Watkins Harper appeals to as wide an audience as possible across race and gender lines to suggest communal nursing and empathy as a path toward finding common ground. It’s hard to hate people up close, as Brené Brown would say. But, as a Black woman nurse, Iola Leroy shows how caring for the wounds of people who are not like us forces all of us to move in closer.

3. Believe in the power of fiction to cultivate empathy

Like Watkins Harper, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps and Charlotte Perkins Gilman similarly suggest the practice of empathy as a method of coalition-building for feminist activism. In their respective works of medical fiction, woman physicians repeatedly ask their male patients and real-world readers to “put yourself in my place for a moment” or “[r]everse our positions” (Phelps 134). They are asking us to sit in the same emotional space. Together. Across the lines of gender and race. In fact, it is often cis-het white men that are asked to do the work of thinking outside their own experiences: Iola Leroy, a Black woman nurse, rejects the proposal of Dr. Gresham, a white male physician, specifically because he fails to see things from her perspective.

Conversely, Dr. Marjorie Yale and Dr. Zay accept their suitor’s proposal because he demonstrates the ability to empathize from a woman’s perspective. Of course, their would-be allies and lovers Dr. Newcome and Waldo Yorke don’t have the added boundary of race to overcome. But, taken collectively, their performances of empathy aren’t really about romance at all. That’s just a marketing ploy to meet the reader’s expectation of happily-ever-after. It’s about modeling the practice of empathy for readers.

Find out more about the politics of women writers of medical fiction in (P)rescription Narratives: Feminist Medical Fiction and the Failure of American Censorship, out now with the Interventions in Nineteenth-Century Studies Series at Edinburgh University Press. Save 30% using code EVENT30 at checkout.

Stephanie Peebles Tavera is Assistant Professor of English at Texas A&M University, Central Texas. She is author of (P)rescription Narratives: Feminist Medical Fiction and the Failure of American Censorship (Edinburgh UP, 2022), which has been described by reviewers as “brimming with hope and intelligence.” She also authored the critical introduction to Helen Brent, M.D. by Annie Nathan Meyer (Hastings College Press, 2020), a medical novel that Dr. Tavera recovered from the archives and for which she won an honorable mention Book Edition Award from the Society for the Study of American Women Writers.