by John White

In the second of a short series of extracts from British Cinema and a Divided Nation (EUP, 2022), John White looks at Downton Abbey (Michael Engler, 2019).

The quick series of shots presented to the audience at the beginning of Downton Abbey (Michael Engler, 2019) operate in combination to create a familiar romantic vision of an England of idealised industrial power, dreamscape rural scenery, and solid imposing buildings that are seen not only to embody history but also to convey a sense of permanence. We see a steam train that turns out to be the overnight mail train, a small village with stone cottages and an ancient church, a sequence of images linked to the Royal Mail including a village post office, a quiet country road, and then, the culmination of all this, a country house set within an expansive landscape. Just as the train we see creates an impact not only in and of itself but also through the way in which it references the famous documentary short, Night Mail (Harry Watt and Basil Wright, 1936), with words by W. H. Auden and music by Benjamin Britten, so the country house prompts the viewer to recall films and TV series that have employed the backdrop of a stately home – including Brideshead Revisited (ITV, 1981), The Remains of the Day (James Ivory, 1993), Gosford Park (Robert Altman, 2001), and the TV series of Downton Abbey (ITV, 2010-15) that has preceded this film. However, what this stylised opening prefigures in the film is not something that can be easily dismissed as mere nostalgic yearning for a lost idyll; the political ideology at the heart of Downton Abbey is something much more fully-formed than a vague desire for former glories. What may at first sight appear to be no more than that nebulous wistful longing repeatedly associated with heritage films is in fact a carefully woven advocacy of one-nation Conservatism.

Typically, the relationship in the film between the family and servants is relaxed and comfortable, and this culminates in the putting out of the chairs for the royal parade. There is no real narrative requirement for this scene to be in the film, it does not move the story on, it does not provide any crucial development of character, but it does give concrete expression to one-nation Conservatism. It is late at night, it is raining heavily, and the chairs have not been set out ready for the royal visit due the next day. You might think the point to having servants is that at moments such as this you can simply send them out to get the job done but that is not what happens. Instead, members of the family and servants work together to achieve a common goal.

Downton Abbey is a celebration of division and inequality, both the characters and the audience are not only expected to be content in the face of a society displaying massive social inequality but to celebrate the fact of such inequality and understand it to be the essence of who they are and what they would want to be. The film works to define the nation and to define Britishness (or more correctly, England and Englishness) viewing it as being built on the foundation of class difference. This is seen, not as a weakness but as the strength of the country. Within this vision, unity and cohesion is achieved through each member of society accepting their role within the fabric of the nation, and the film rejoices in the resulting version of Britishness. It is the layering of society as rich and poor, master and servant, that gives Britain its form, structure and greatness, and it is because of their acceptance of this order that the different levels of society are able to work together at times of crisis. There is an expectation on the part of the lower orders that the upper echelons should display their rank and status. Those in domestic service celebrate the wealth and splendour of upper class life as much as, if not more than, the upper classes; and the upper classes perform their wealth and splendour in such a way as to satisfy a requirement in the lower orders to be able to take pride in the whole aristocratic-cum-royal-cum-imperial edifice. Each class is fulfilling its role within a unique expression of nationhood, and this political perspective is embodied in the totality of what we are shown as being ‘Downton Abbey’.

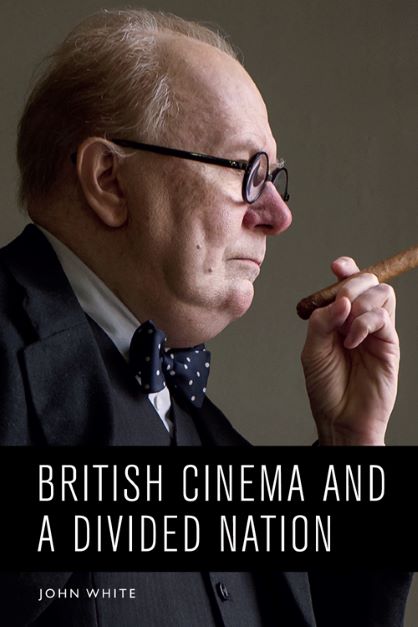

About the Book

British Cinema and a Divided Nation examines representations of the nation found within contemporary British cinema, against a backdrop of rising political tensions and deepening social divisions following the ‘Brexit’ referendum of June 2016.

About the Author

John White is an independent scholar who until recently taught film at Anglia Ruskin University. He is co-editor of Fifty Key British Films (Routledge, 2008), Fifty Key American Films (Routledge, 2009) and The Routledge Encyclopedia of Films (Routledge, 2014). He recently contributed chapters to books on Budd Boetticher and Delmer Daves in the Edinburgh University Press ReFocus series, and is the author of Westerns (Routledge, 2011) and European Art Cinema (Routledge, 2017) and The Contemporary Western: An American Genre Post-9/11 (EUP, 2019).

Sign up for our mailing list!

Interested in learning more about this book and other titles from Edinburgh University Press? You can sign up for our mailing list here!

You can also read more of our film studies blogs here.