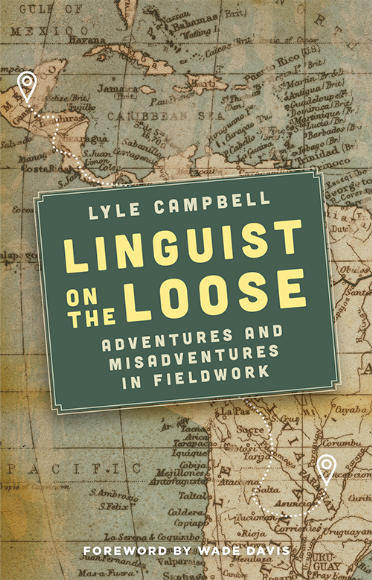

In this extract from the introduction of his new book Linguist on the Loose, Lyle Campbell explores why and how linguists work with endangered languages.

by Lyle Campbell

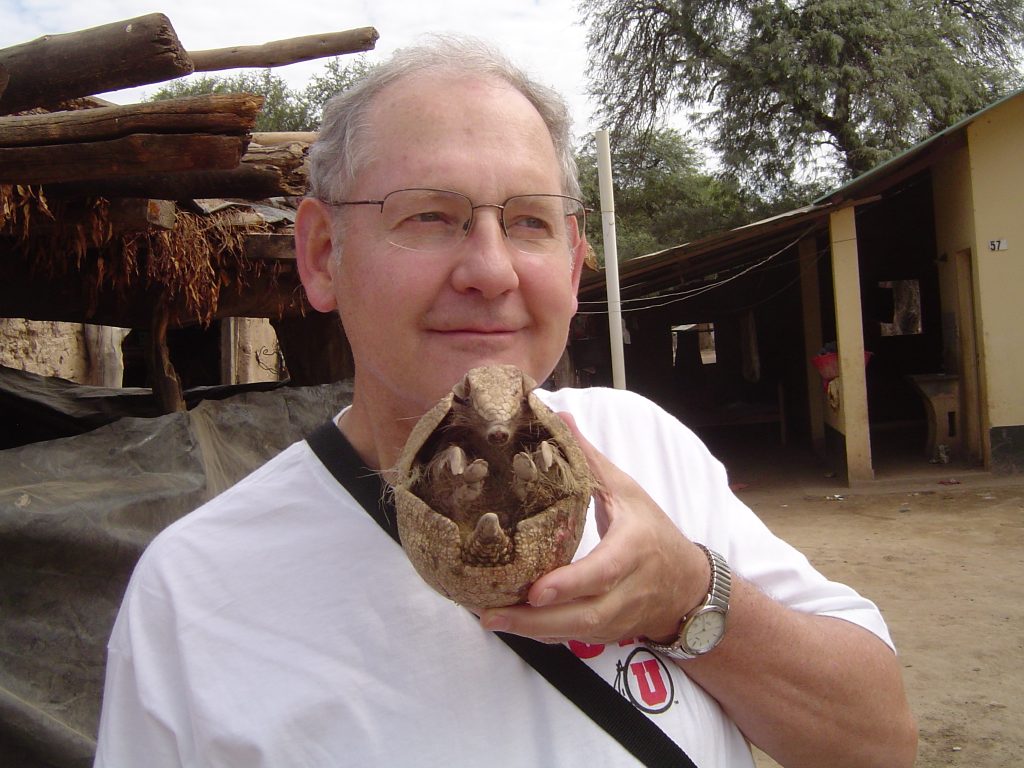

In my mind I have always been a country boy; I grew up mostly in the woods in Oregon. However, my business card—rarely used though provided by my university—says I’m a Professor of Linguistics. I’m the kind of linguist who has done a lot of fieldwork, on a fair number of languages.

What’s a linguist?

So, first, what is a linguist? A linguist, as academics use the term, is definitely not just someone who knows a bunch of languages, as is sometimes thought. That’s a polyglot; some linguists are also polyglots but most are not.

The answer to the question “So what’s a linguist?” really has nothing to do with knowing a language or about the question “How many languages do you speak?” Rather, linguists investigate and analyze languages for particular purposes, and different linguists have many different reasons for choosing and studying the languages that we do and for doing the kind of research we do.

In my case, for many of the languages I got involved with my purpose was to describe (to document) endangered languages, those languages at risk of being lost, to discover as much as I could about what is possible in human languages, how their pieces fit together, what makes them tick, how and why languages change and what their histories tell us about the history of the people who speak them, and to provide source materials for communities and individuals interested in conserving or revitalizing their languages and using the documentation for educational purposes.

Why is there a need for documenting endangered languages?

It is difficult to overstate the seriousness and severity of the language endangerment crisis. The Catalogue of Endangered Languages reports around 3000 endangered languages (c 45% of living languages) on all continents except Antarctica and in nearly all countries of the world with very few exceptions. That is a shocking proportion of the overall linguistic diversity of the planet that is at risk.

Why does language endangerment matter?

Social justice and human rights

Language loss is often not voluntary; it frequently involves violations of human rights, pushed by political or social repression, oppression, suppression, aggression, prejudice, violence, and at times by ethnic cleansing and genocide. It is simply a matter of right and wrong—and that should matter to us all.

A closely related reason for grave concern for language endangerment is because their languages matter immeasurably to the people who use them and identify with them, full stop. Language loss is typically experienced as a crisis of social identity.

Human concerns

Languages are treasure houses of information for history, literature, philosophy, art, and the wisdom and knowledge of humankind. Their stories, ideas, and words help us make sense of our own lives and of the world around us—of human experience, of the human condition in general. When a language becomes dormant without documentation, we lose incalculable amounts of human knowledge.

The life-enriching value of literature is well understood—“by studying literature, we learn what it means to be human” (CliffsNotes n.d.). This is equally true of the oral literatures of the Indigenous peoples of the world. They, too, have struggled with the complexities of their world and the problems of life, and the insights, discoveries, and artistic creations represented in their literatures—whether written or oral—are of no less value to us all. When a language loses all of its speakers without documentation, taking into oblivion all its oral literature, oral tradition, and oral history with it, all of humanity is diminished.

Great reservoirs of historical information are contained in languages. The classification of related languages teaches us about the history of human groups and how they are related to one another, and we gain understanding of contacts and migrations, the original homelands where languages were spoken, and past cultures from the comparison of related languages and the study of language change—all irretrievably lost when a language is lost without adequate documentation.

Loss of knowledge

The world’s linguistic diversity is often considered one of humanity’s most valuable treasures. This means that the loss of the hundreds of languages that have already been lost is a cataclysmic intellectual disaster, on many different levels.

To cite a single example, encoded in each language is knowledge about the natural and cultural world it is used in. That knowledge is often not known outside the small speech communities where the majority of endangered languages are spoken. When a language is lost without adequate documentation, it takes with it this irreplaceable knowledge. It is argued that loss of such knowledge could have devastating consequences even for human survival.

A telling example comes from Seri, a language isolate of Sonora, Mexico, with about seven hundred speakers. The Seri have knowledge of “eelgrass” (Zostera marina L.) and “eelgrass seed,” which they call xnois. It is “the only known grain from the sea used as a human food source . . . eelgrass has considerable potential as a general food source . . . Its cultivation would not require fresh water, pesticides, or artificial fertilizer” (Felger and Moser 1973: 355–6). Seri has a whole set of vocabulary dealing with eelgrass and its use. According to the argument, it is all too plausible to imagine a future in which some natural or human-caused disaster might compromise land-based crops, leaving human survival in jeopardy because of the loss of knowledge of alternative food sources such as the knowledge of eelgrass reflected in the Seri language.

This Seri case is an example of the specific knowledge that is often held by the smaller speech communities of the world—knowledge of medicinal plants and cures, of plants and animals yet unknown to Western science, of new crops, etc. Documentation of the languages of small-scale societies and of the knowledge they hold has significantly benefitted humanity.

When a language is not learned by the next generation, typically the knowledge encoded in the language fails to be transmitted. Most obvious in many cases is loss of the cultural knowledge about traditional medicines, the environment and ecology, about uses of plants and animals, modes of subsistence, fishing and hunting, horticulture, and also the many aspects of culture involved in ritualistic, poetic, esthetic, artistic, and other cultural functions of the language being lost. Loss of linguistic diversity and with it these kinds of knowledge means loss in the range of potential ways of understanding the world.

So, it is argued that reduction of language diversity diminishes the adaptive strength of humans as a species because it lowers the pool of knowledge from which we can draw for survival.

Consequences for scientific understanding of human language

A major goal of linguistics is to understand human language capacity and human cognition through the study of what is possible and impossible in human languages. The discovery of previously unknown linguistic features as we document little-known languages contributes to this understanding and advances knowledge of how the human mind works. Conversely, language loss is a horrendous impediment to achieving this goal.

Documentation of endangered languages has frequently and repeatedly demonstrated the importance of getting adequate documentation of these languages. The discovery of previously unknown linguistic traits is helping linguists to comprehend the full range of what is possible in human languages, a central goal of linguistic theory.

Of crucial importance is making the fieldwork sensitive to and responsive to the needs and interests of the people whose languages are involved, collaborating for language revitalization and language conservation.

This look at the status of the world’s languages and at why linguists feel so strongly about language documentation and about collaborating with communities to help strengthen or revive their languages provides the context and background for the fieldwork experiences reflected in the chapters of this book.

About the author

Lyle Campbell is an American scholar and linguist known for his studies of indigenous American languages and historical linguistics. He is the author of 21 books and 200+ articles, cofounder of the Catalogue of Endangered Languages, and member of the Governance Council for the Endangered Languages Project.

Linguist on the Loose is available to order now from Edinburgh University Press.

Liked this post? Read more in Language and Linguistics.

More from Lyle Campbell:

Stay up to date on all things Language and Linguistics at Edinburgh University Press – click here to sign up for our email newsletter.