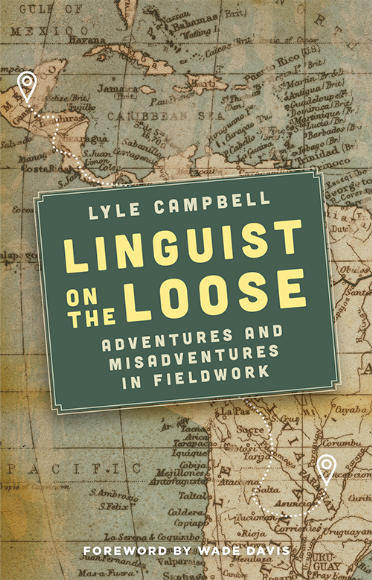

In this exclusive interview, renowned linguist Lyle Campbell discusses his career in linguistic fieldwork, the topic of his new book, Linguist on the Loose: Adventures and Misadventures in Fieldwork.

Tell us a bit about Linguist on the Loose, why did you write it?

The book is about my linguistic fieldwork experiences – some wonderful and rewarding, others vexing and harrowing – with a considerable number of languages in many places. I hope that sharing some of the things I learned from these experiences would be useful to others who do fieldwork or contemplate doing it or just want to know about it.

I wanted to let others know of things about fieldwork that I learned the hard way, things that are not talked about in other writings about fieldwork. I also wanted to call attention to the plight of endangered languages and to the need for documentation and revitalization of these languages.

What inspired you to research endangered languages?

Part interest and part accident. As an undergraduate, I studied archaeology. I loved archaeology but I wanted to do something that could help people, and so I switched to linguistics. During my graduate student years I had been a research assistant on two separate projects to write a pedagogical grammar for the Peace Corps, one for Kaqchikel (a Mayan language of Guatemala) and the other for Cuzco Quechua. Pursuing linguistic research with the indigenous languages of Latin America just seemed to follow naturally from these earlier interests and experiences. In those days there were few linguists working with these languages and little was known about many of them – many were severely endangered, and much work was needed. I felt that was my calling.

What advice would you give your younger self about doing linguistic fieldwork?

Be much better prepared and informed, especially about health issues, but also about potential problems from politics, bureaucracies, communications, transportation, local cultures, and many other not strictly linguistic things.

What is the biggest way the world has changed since you began working in linguistic fieldwork?

It is a different world today from when I began doing linguistic fieldwork.

Perhaps the biggest change is in the role that fieldwork and language documentation play in Linguistics. Before about 1990 language documentation held no prominent place in the discipline. After c.1990, recognition of the language endangerment crisis brought about a shift. Now documentation of endangered languages is considered of the highest priority in Linguistics.

Earlier, concern with threatened languages aimed largely at obtaining scientific information on them before it was too late, and there was much less direct involvement with the communities where the languages were spoken and with language revitalization. Now, nearly all who do language documentation are also involved with revitalization of the languages and concerned that results of their work be of service to the language communities. Now there are a sizable number of indigenous students and scholars involved in documentation and revitalization of their languages; when I began, there were extremely few indigenous scholars. It is gratifying that now there is a formally recognized subfield dedicated to language documentation and to language revitalization, with its own resources and tools and strategies, conferences and publications.

Perhaps the other largest changes involve access to information. When I began as an undergraduate, there were no photocopy machines, no personal computers, no internet. There was no Google or other search engines – there were the drawers of the file catalogue in the library. Portable tape-recorders became available as I began fieldwork research; I went from heavy, clunky reel-to-reel to cassette to CD to digital recorders. Recording equipment became much more sophisticated, with vastly higher quality and, of course, more reliable storage of recordings became possible. There were no software tools to help in data collection and data management and analysis, no dedicated language archive. Since the arrival of the internet, vastly more is known and the information is vastly easier to access, all facilitating research almost immeasurably.

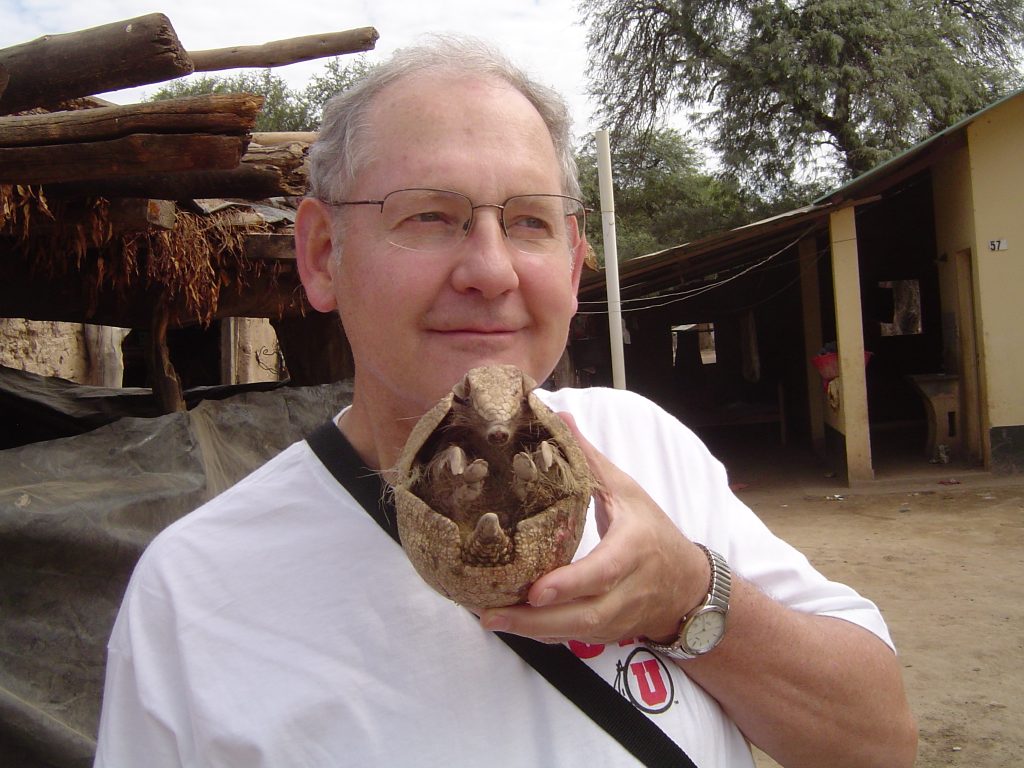

Your book is well illustrated with photos from your fieldwork – is there one with a particularly good story behind it?

Let me answer this question in a different way. I lost all the photographs I had in a fire in 2001, so almost all of the pictures in the book are photos of fieldwork done later. (I was on sabbatical and had put everything in storage, planning to get a different house when I returned; the storage facility burned up.) All the pictures I had of language consultants and fieldwork from before that time were lost, including the ones of the last speakers of several languages that are now no longer spoken.

Though I lost everything I owned, the most heartbreaking thing about that fire was loss of these photos. I wish the fieldwork with those people and places and their languages talked about in the book could have been also represented in photos in the book. As for the photos that are in the book, there is an interesting story behind almost every one that I wish there were time and space enough to tell.

What is something the reader could do to support the fight against language endangerment?

Readers can donate to the several non-profit organizations that foster documentation and revitalization of endangered languages. Some relevant ones are:

- The Endangered Languages Fund (ELF)

- The Endangered Languages Project (ELP)

- Foundation for Endangered Languages (FEL)

- And others!

I hope readers will donate to these organizations. Much work is needed but funding to support it is very limited.

Readers can also become informed themselves and help to promote the cause and make others aware of the language endangerment crisis and the needs. They can try to urge and influence politicians, civic leaders, media persons, and decision-makers and policy-makers of various sorts to support and foster the cause. Readers with relevant skills may be able to contribute directly by volunteering their service for certain projects or agencies.

It is important to say also, don’t meddle and make things worse! For untrained and uninvited outsiders just to show up at some Indigenous community expecting to collect some language information is almost never successful and typically has very negative consequences.

Back on a more positive note, the book explains many of these issues. I hope readers will like it.

About the Author

Lyle Campbell is an American scholar and linguist known for his studies of indigenous American languages and historical linguistics. He is the author of 21 books and 200+ articles, cofounder of the Catalogue of Endangered Languages, and member of the Governance Council for the Endangered Languages Project.

Linguist on the Loose is available to order now from Edinburgh University Press.

Liked this post? Read more in Language and Linguistics.

Stay up to date on all things Language and Linguistics at Edinburgh University Press – click here to sign up for our email newsletter.